By the time Stephen Harper formed his first minority government in January 2006, then-president George W. Bush’s surprising AIDS initiative was in full stride. The President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief — PEPFAR — was a commitment of billions of dollars to fight the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. PEPFAR has been the one great positive achievement of the Bush presidency, dramatically increasing the number of people in poor countries receiving life-saving HIV treatment.

Mr. Bush’s PEPFAR gave hope that Mr. Harper might follow suit. So did the swift non-partisan commitment of funds by the previous Liberal government for international efforts to fight AIDS and related diseases. So did the enactment in 2004, by a unanimous vote in Parliament, of Canada’s Access to Medicine Regime. CAMR was designed to increase the supply to poor countries of affordable generic versions of expensive patented drugs to combat HIV and other public health problems.

Alas, the six years since have been largely a tale of disappointment. From the first possible moment, Mr. Harper and his government have demonstrated a mystifying ambivalence in responding to a challenge that has cost the lives of many millions and, despite dramatic progress, threatens millions more.

It took only months for the new Prime Minister to demonstrate his deep personal discomfort with the entire AIDS issue. By chance, in August 2006 Toronto was host of the biannual International AIDS Conference, the primary summit for all those around the world interested in AIDS; Microsoft’s Bill Gates and Bill Clinton both attended and spoke. The conference attracted heavy media coverage, especially in Canada, making it the perfect setting for the new government to send a message.

It did. Invited to speak at any time that suited his schedule, Mr. Harper declined to attend. In a well-reported statement, conference co-chairman Mark Wainberg, one of Canada’s most renowned AIDS researchers, did not hide his anger from his huge audience:

“We are dismayed that the prime minister of Canada, Mr. Stephen Harper, is not here this evening…The role of prime minister includes the responsibility to show leadership on the world stage. Your absence sends the message that you do not consider HIV/AIDS as a critical priority, and clearly all of us here disagree with you… As a Canadian it breaks my heart.”

Tony Clement, then Minister of Health, attended in Mr. Harper’s place. Despite repeated rumors that Mr. Clement would make a major funding announcement, he did not. On World AIDS Day, Dec. 1, 2006, Canada did announce a welcome contribution to the fight against AIDS, but it was far from the standard set by Mr. Bush and unhappily modest in terms of actual need.

Two months later, in February 2007, in what one news story called “a glitzy photo-op,” Mr. Harper and Mr. Gates jointly announced major new funding to accelerate the development of an HIV vaccine, the elusive holy grail of AIDS research. But by August, according to a report prepared for the Public Health Agency of Canada, red tape and turf wars had blocked the flow of money and a much-hyped plan to build a vaccine plant in Canada was soon forgotten, sunk without a trace.

Everyone could agree on the need for a vaccine. But there is profound disagreement on measures to prevent HIV among people injecting drugs. Like researchers and activists everywhere, those in Canada had long supported harm reduction measures to limit the possible secondary effects of substance use, such as the spread of HIV and AIDS and Hepatitis C. Prior to the Harper government, including such measures as part of a comprehensive approach was explicit in Canada’s official drug strategy. This presumed consensus was ruptured conclusively in the 2007 Conservative budget when harm reduction was completely abandoned.

Although the science documenting the benefits of harm reduction programs was overwhelming, programs such as Vancouver’s safe injection site, called Insite, drove the Harper government crazy. Such services, it appears, are at odds with the doomed “war on drugs” the government is determined to intensify, as its recent omnibus crime bill again demonstrated.

The government hardly disguised its feelings. Health Minister Clement provocatively chose the 2008 International AIDS Conference in Mexico City to declare that “Insite is an abomination and you can put that on YouTube!”, which was of course promptly done. No amount of compelling evidence has ever shaken the Harper government’s view that Insite simply “enables” drug users, and it did all in its power to shut it down. The Insite issue went all the way to the Supreme Court, which rebuffed the government last year by ruling unanimously that the facility could remain open.

Such battles highlighted the deepening divide between a government intent on ignoring or distorting science and most of the Canadian AIDS community, from senior academics, scientists and medical specialists to local street activists.

Back in 2006, the same Mr. Clement had however briefly raised hopes by promising to fix Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime (CAMR), described earlier. Mr. Clement even boasted that he had consulted on the question with Stephen Lewis, then the Special UN Envoy for AIDS in Africa and probably the most influential advocate anywhere for escalating the life-and-death struggle against AIDS.

From the get-go, as virtually all observers agreed, the project had been sabotaged by the backroom lobbying of the powerful multinational drug companies. As a result, in the eight years since CAMR was introduced, exactly one licence has been issued to ship one order of one drug to one African country. Yet a properly functioning CAMR, according to an outraged James Orbinski, one of Canada’s leading experts in international health, could help save “hundreds of thousands if not millions of lives” in Africa and other poor regions. Surely this was a no-brainer for the government. CAMR, offering greater access to medicines, was the logical complement to Mr. Harper’s much-ballyhooed project to improve maternal and child health in poor countries.

But with Big Pharma active as ever, Mr. Clement’s bold commitment was soon toast. In the dying days of the 2008-2011 minority parliament, a majority of MPs (including a number of Conservatives) finally passed Bill C-393, which would have at last have permitted the export of inexpensive Canadian-made generic drugs to poor countries. But it was not to be. The government, led by the Industry Minister, the ubiquitous Mr. Clement, arranged for the Conservative-dominated Senate to scuttle the legislation.

But the fight is not over. The bill has been re-introduced in Parliament as Bill C-398 and AIDS advocates across the country are girding for the task come the fall session. Has it a realistic chance of passing this time? Well, there are six years of reasons for modest expectations. Only last week the Globe and Mail reported that the Public Health Agency of Canada cut funding to the internationally respected Canadian HIV and AIDS Legal network on the bizarre grounds that some of its activities might lead to advocacy, as if the entire struggle to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS hasn’t been based on relentless advocacy.

And yet…

The government recently made a modest increase in Canada’s contribution to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Fixing CAMR would earn Mr. Harper, for the first time, the plaudits of the entire country, beginning with this writer. The Prime Minister now has his cherished majority government. Maybe the remarkable success he has achieved will lead him to envisage a personal legacy in the historic battle against the pandemic comparable to George W. Bush’s. After all, nothing less than “hundreds of thousands if not millions of lives” are in Mr. Harper’s hands.

This article was first published in the Globe and Mail.

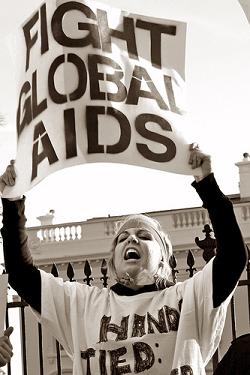

Photo: IntangibleArts/Flickr