The French economist Thomas Piketty, author of the best-selling Capital in the Twenty-First Century, had this to say in a recent interview: “A lot of people argue that the First World War in particular was a sort of nationalist response to the very high social tensions and inequalities that characterized pre-World War I European countries and I think that there is a lot of truth in that.”

The scholar Karl Polanyi is arguably the most distinguished of such people. Among the enormous tensions and trauma generated by the transition from pre-industrial to industrial societies, Polanyi, paradoxically, saw the widely worshiped international gold standard that sprung up to underlie the great wave of globalization as itself a key part of the problem.

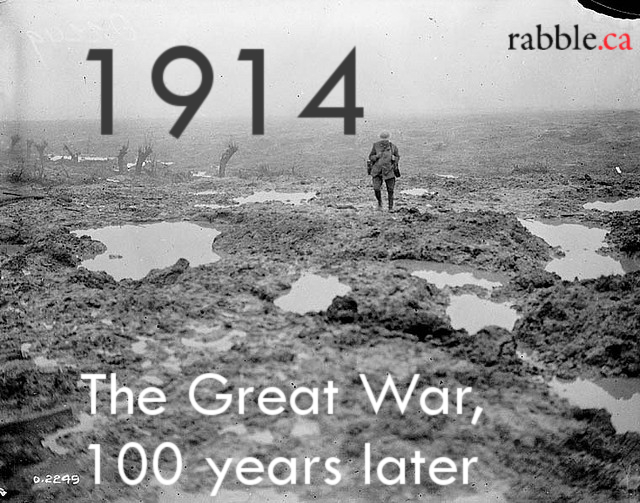

Liberal capitalism was flawed at its core. “Prosperity” led to the catastrophe of the First World War, and opened the door to the Great Depression, fascism, and the Second World War. This was, and is, a long way from the conventional wisdom.

Polanyi, one of the great intellectuals of the twentieth century, author of The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (published in 1944 and still in print), who was born in Hungary in 1886, fought in the First World War as a cavalry officer for Austria-Hungary on the eastern front (allied with Germany, against Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia). Almost half of his officer corps was lost or missing by early 1915, double that of Russia and triple that of Germany; Polanyi survived the war, though ill and injured.

Moving after the war to Vienna to work as a socialist journalist, with the spectre of fascism he fled to England in 1934 to lecture for the Workers’ Educational Association and then to the United States, at Bennington College and Columbia University. (His wife was denied entry in the U.S. because she had been a member of the Communist Party in Hungary after the war, so they took up residence in Canada, at Pickering near Toronto. Their only child is the distinguished Canadian political economist Kari Levitt Polanyi.)

From his arrival in London Polanyi began work on what became his The Great Transformation, where he offers a sweeping analysis of European history from the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the Napoleonic Wars — late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries — through the long peace (no European-wide war) till 1914, and its aftermath. The First World War is the first of a sequence of linked catastrophes.

Throughout the millennia, what today we call without thinking about it “the economy,” in fact did not exist independent of the society in which it was embedded. Hence it had no autonomy of its own, no fatal utopian pretension that it was self-regulating.

The Industrial Revolution changed all this, as the market economy, to the accompaniment of unleashed technology, assumed autonomy in its own right, creating unprecedented economic benefit, though unequally distributed, while at the same time, imposing increasing economic vulnerability and social cost at home and imperialism abroad.

For Polanyi, the economy was disembedded from society by the creation of markets for what he called the “fictitious” commodities, land, labour and money. Money, in the guise of the gold standard, was the central pillar of the international economy as it evolved in the nineteenth century.

The operation of the vastly enlarged market for real commodities compelled a means by which multiple national currencies could be made convertible and brought under a single control. That means was the gold standard which imposed its discipline on all countries. The creation of national currencies was made subject to an automatic mechanism, another of man’s ingenious inventions, the better to enable the impossible pursuit of utopia.

The irony of the gold standard, as the hallmark of internationalism, was that it only worked if national governments let it work, indeed, made it work. If a country was importing more than it was exporting, more than it could afford, then gold must flow out, money supply and credit must be reduced, and the result would be austerity, deflation and economic crisis, which government then had to cope with. (While the euro zone is not identical to a gold standard within Europe, what is happening in Greece today, with imposed and re-imposed austerity, sounds all too familiar.)

There was hence imbedded in the system an inherent tension between the national and the international. National business could aggressively push exports and risk international conflict between governments. The rush for colonies — the manic, competitive, scramble for Africa in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries — was a means by which each imperial nation could create new protected markets for its exports. Governments were constantly tempted to limit imports, through protective measures, likewise generating tensions.

The risk of open conflict, of war, hung about, being further exacerbated by the generalized consolidation of nation states and the flourishing of nationalisms, which has long been seen by historians as destabilizing a fortuitous balance of power post-1815. As the gold standard became widespread after 1870, Polanyi saw external tensions worsening, culminating in 1914. Liberal capitalism, rather than being self-regulating, was self-destructive.

As the nineteenth century passed, it did so at an increasing speed. Things spun out of control. War came as if from nowhere — and surely would be quickly over.

Note that Polanyi is blaming the gold standard itself, not high finance, as Lenin does, for aiding and abetting the First World War. Indeed, Polanyi goes so far as to count high finance, minting money from trade and debt, as a force for peace — which is not to deny that it could, if it had to, do well enough out of war.

There’s a ring of inevitability in Polanyi’s analysis that is anathema to the historian who cannot avoid seeing in the archives the contingency of it all. What can be said is that Polanyi gives a context to the nineteenth-century international economy that allows for the possibility of what actually happened.

What actually happened was the First World War as a truly pivotal event that opened the gates to hell. That watershed, that violent birth of modernity, is central to the story that Polanyi tells. It has that ring of truth about last century’s inexplicable descent into barbarism.