Margaret Thatcher is dead. Her policies as prime minister ruined the lives of millions of people. Now her political heirs are trying to extend the damage she did in ways she only dreamed of.

The great political task before all of us is to ensure they fail. We need to make sure Thatcher’s legacy dies with her.

Those who will mourn the death of Margaret Thatcher include the bankers and get-rich-quick speculators in the City. She pioneered the neo-liberal casino capitalism which enriched them. So will Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers, which have done so much to champion her rotten values. The big business parasites who got rich from the privatisation of public utilities will no doubt recall her with fondness.

Many of us won’t mourn the death of Thatcher. The millions who lost their jobs as manufacturing was run down, whole industries ruined and unemployment rose, and the ex-miners, their families and their communities who fought Thatcher’s government in the Great Strike of 1984-85, won’t mourn. The Liverpool families who fought for justice for the victims at Hillsborough for 23 years against an establishment cover-up will not mourn.

Many more — all those who reject a competitive ideology of dog-eats-dog, the race to the bottom in pay and conditions, and the vicious divide-and-rule that goes with it — will not mourn Thatcher’s passing.

Thatcher’s class war

The left are sometimes described by right-wing newspapers as trumpeting ‘class war.’ The truth is that Thatcher was a class warrior for the rich and powerful, the leading class warrior of her generation. From the moment of her first government’s election in 1979, her mission was to shift the balance of wealth and power from the vast majority to a wealthy elite. She pushed through policies of privatisation and de-regulation, used the fear of unemployment to discipline those in work, and brought the market into public services.

Thatcher attacked a series of groups of workers and their trade unions — from the steelworkers in the early 1980s to ambulance drivers at the end of the decade, via the miners, printers and many more, in a concerted effort to destroy working class resistance to her right-wing agenda. She wanted to ‘free up’ public services and public utilities so the Tories’ rich friends could profit from them. She sought to remove any barriers to the accumulation of wealth in the hands of the few.

Thatcher was more than just a domestic political figure. Globally she — alongside U.S. president Ronald Reagan — became an icon for the neoliberal model. She was famously friends with General Pinochet, who oversaw the killing of thousands of socialists so that corporations could plunder the country’s resources and exploit its working people. Thatcher was a cheerleader for IMF programmes imposed on developing countries, opening up their markets to powerful Western corporations and selling off public resources.

Thatcher was deeply committed to NATO and in particular the alliance with U.S. imperialism. Her governments wasted billions on nuclear weapons and worked closely with the White House and Pentagon. She shamelessly used war in the Falklands to boost her waning poll ratings at home.

While systematically eroding the notion of a welfare state that cares for people from cradle to grave, Thatcher boosted the coercive power of the state. This was most obvious in the Miners’ Strike, during which she characterised the miners as ‘the enemy within’ and sanctioned massive police brutality against pit communities, and an approach to Northern Ireland which demonised resistance to the British imperialist state and bolstered discrimination against Catholics. She let Republican prisoners starve in northern Ireland’s jails. In the UK ‘mainland,’ at a similar time, racist police attacked those who had the nerve to riot in conditions of poverty, hopelessness, racism and alienation.

The tide turns

Thatcher’s undoing was the poll tax. Shortly before Thatcher was ousted as prime minister, in 1990, socialist journalist Paul Foot wrote:

“The anger has flared up over the hated poll tax, which attacks everyone except the rich and has succeeded in uniting opposition to the Thatcher government for the first time. From the north of Scotland to the Isle of Wight, the biggest movement of civil disobedience in Britain this century has persuaded hundreds of thousands of people to resist the tax by not paving it… But the new anger does not stop at the poll tax. It has become the symbol of all the other Tory plans and policies.”

The tide had turned. The Tories limped on for several years, with John Major as leader and with a tiny minority after the 1992 election, but the myth of Tory invincibility had been destroyed. In the 1990s there was a decisive shift in the opinion polls, leading to a Labour landslide in 1997. Large numbers of working class people never accepted Thatcherism; many more turned against it as the harsh realities of unemployment, repeated recessions, growing inequality, the chaos and waste that followed privatisation and the injustice of the poll tax were felt.

But, while the Labour landslide of 1997 reflected a popular rejection of Thatcher’s values, Blairism was a mark of Thatcher’s political legacy: she shifted mainstream politics to the right, pulling successive Labour leaderships along with her, relentlessly insisting ‘There is no alternative.’ The acceptance of neoliberalism by the Westminster political class, reflected in New Labour’s policies during 13 years in office, is a reflection of success for the Thatcherites.

Despite all this, opinion polls have repeatedly shown large majorities opposed to privatisation, there is widespread hatred of Thatcher’s legacy and a powerful mood of opposition to establishment politics. It is not that working class people have become convinced of Thatcherism. Our weakness is in organisation. Trade unions have been hammered by defeats, Labour has shifted rightwards and the organised left is small.

Confronting the heirs of Thatcherism

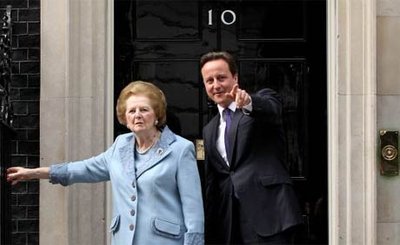

We now face a Tory-led government that aims to build on Thatcher’s legacy and extend it. Cameron and Osborne want to weaken the welfare state more thoroughly than Thatcher’s administrations could ever hope to. This month’s punitive series of welfare ‘reforms’ — including the despised bedroom tax – are a raid on the poor while the millionaires get a tax cut. Thatcher left the NHS largely intact, but now it is being carved up.

The pay freeze and pensions cuts for millions of public sector workers are a sustained assault on living standards. Anti-union laws remain in place, the police are used to curtail protests and the right-wing press demonise those who need social security.

The Tories and their ideas are not popular. Our challenge is to mobilise the opposition that exists in every area and bring it together in a concerted mass movement that can end austerity and bring down the government. Many thousands have joined demonstrations in defence of the NHS and in recent weeks there have been scores of local protests against the bedroom tax. A number of trade unions are considering a renewal of much-needed strike action to confront the attacks on pay, pensions and public services.

The People’s Assembly Against Austerity — in London’s Westminster Central Hall on June 22 — can connect and co-ordinate the struggles against cuts, planning mass action against this government of Thatcher’s children. Thatcher’s legacy lives on. So does the legacy of opposition, resistance and alternative ideas about the kind of society we need. Our task is to turn that into an organised social force capable of burying Thatcherism for good.

Alex Snowdon is an activist and writer based in Newcastle.

This article was originally published in Counterfire and is reprinted here with permission.