On this past December 5, we learnt on the front page of the daily Devoir that college-level instruction provided to inmates was now in jeopardy because of the federal cuts in Flaherty’s last budget. At Collège Marie-Victorin in Montréal, these cuts could bring an end to 40 years of inmate instruction for reintegration purposes. Incidentally, provincial cuts put into place to reach budgetary balance must be added to the federal cuts.

This bad news for proponents of rehabilitation is the logical follow-up to the allegedly “tough on crime” Conservative initiatives in corrections policies.

At the beginning of 2012, omnibus Bill C-10 was voted into law by the Canadian Parliament. The Safe Streets and Communities Act, as it is officially called, has been denounced across Canada and notably in Quebec. Indeed, the Minister of Justice at the time, Jean-Marc Fournier, repeatedly travelled to Ottawa to defend the province’s point of view. The National Assembly granted its unanimous support to the initiative. Each time he came back empty-handed.

Quebec (like at least seven other provinces) condemned at the time the costs induced by the bill’s multiple clauses, a set of measures aimed mostly at forcing an increase in the length of prison sentences. Many of these measures had long been part of Conservatives’ plans but, being short of a majority in Parliament, they had not been able to vote them into law.

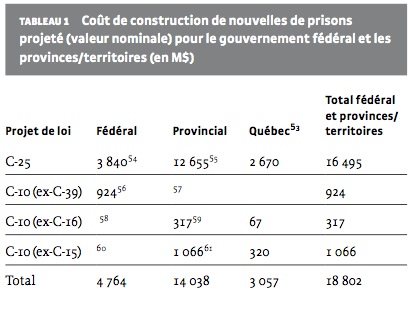

A year ago, IRIS published an evaluation of the costs that Bill C-10 might induce.

But Quebec was not only condemning the costs of the federal bill, the province was critiquing the destabilizing effect it could have on its rehabilitation practices, in particular those regarding youth. In October, the youth centres’ directors were worried for instance about the consequences of putting an end to the confidentiality of certain juvenile delinquents. The Commission des droits de la personne et de la jeunesse also came out last February against Bill C-10 for the same reasons.

There is no need here for us to plunge back into the repression vs. rehabilitation debate. It’s now over and we all know who has won. Everyone, except Stephen Harper’s Conservatives and senator Pierre-Hughes Boisvenu.

Let us note that the Conservatives’ recipe in this respect sadly resembles the tough-on-crime approach applied in the United States in the last decades, which appears to have been a resounding failure. In one of the most covered cases, Arizona has voted into effect a controversial law, the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act. Even the name bears a striking resemblance to the new Canadian law.

One of the anticipated effects of this law in Arizona is to allow police officers to resort from now on to racial profiling and to impose prolonged incarcerations for illegal immigrants.

These detentions will increase the number of inmates and therefore the business opportunities for U.S. private prisons. The stakes in this issue are so high that they were not content with celebrating the adoption of the law: they downright wrote the law, as revealed an unsettling NPR report.

Apparently, that’s what they call over there a “public-private partnership”: the private sector writes the laws, then the elected representatives vote them in…

Since Bill C-10 will increase prison population, the question which follows naturally is where will we put all those prisoners? Is the Canadian government thinking of calling on the private sector as in the U.S.?

Signs of a privatization of detention are accumulating in Canada and, as in Arizona, migrants are already paying the price. For the moment, there are no private prisons, but detention firms are going into the asylum seekers’ incarceration “market.”

According to The Guardian, the Minister of Immigration Jason Kenney visited private prisons in Australia and private incarceration businesses are lobbying the government.

Whilst the Quebec Bar rarely takes a political stand, it asked for the courts’ opinion on Bill C-10 in November. The lawyers’ professional corporation hopes to invalidate the clauses which reduce justice’s power by limiting judges’ leeway, a measure which they find to be unconstitutional.

It’s not the first attempt to oppose the bill now passed into law. As early as 2011, the Quebec government was searching for ways of bypassing its problematic clauses. Many tactics were considered: to retain within a package only the charges which are not subject to minimum sentencing, to resort to plea bargaining, to withhold from the evidence certain details (not mentioning the number of pot plants to avoid reaching the six-plant minimum which leads to a minimum sentence), etc.

The new PQ Minister of Justice Bertrand St-Arnaud quickly and openly threw himself into Bill C-10 bypassing by instituting a Quebec court-supervised drug treatment program. The government’s press release is clear on the aim of this announcement:

“By acting in this way, it thus gives judges the possibility not to impose the new minimum sentences when the offender is successfully engaged in the drug treatment program, in conformance with article 10(5) of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.”

This is Quebec’s response to a federal Ministry of Justice study which foresees that imprisonments related to marijuana grow operations will increase fivefold. The Canadian Association of Crown Counsel itself anticipated that Bill C-10 would overload the justice system.

This article was written by Guillaume Hébert, a researcher with IRIS, a Montreal-based progressive think tank.