Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

The acquittal of Jian Ghomeshi and, most especially, the judgement from Justice William Horkins that went out of its way to vilify the victims in the case and to perpetuate basic rape culture myths, has been met with widespread outrage and anger in many quarters.

Predictably it has also been widely celebrated , or apologized for, by the usual suspects and in the usual ways that one would expect.

Generally those who seek to justify the verdict do so by disingenuously acting as if the outcome, the tactics used by the defense and the contemptuous attitude of the judge are somehow unique to this case. That the outcome of a man walking free despite multiple complainants is somehow unique to this case. That a man getting away with the sexual assault of women is somehow unique to this case. That the “whacking” tactics and excessive scrutiny of the conduct of the victims after the assaults occurred (as opposed to, say, perhaps taking a look at the subsequent conduct of the accused) is somehow unique to this case.

That it was all really only about the rights of the accused and the details of this specific case.

The problem with that view, even if you accept its premises, is that the Ghomeshi trial and verdict did not occur in a vacuum. At all.

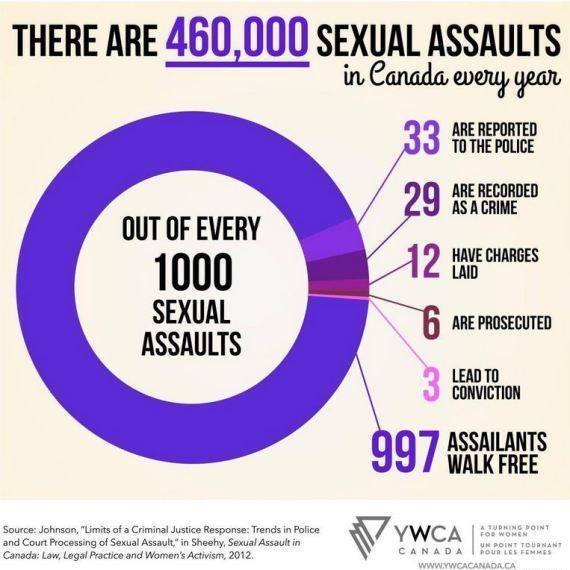

It occurred in a society and a context where over 99% — over 99% — of sexual assaults result in no judicial consequences for the perpetrators of any kind.

Only a fraction of assaults are ever reported, only a fraction of those result in serious charges, and only a small fraction of those result in convictions.

There is no other crime where the victims are treated in an analogous way, where the wheels of justice so rarely turn and where turning to the courts, the police and the crown turns out to be so frequently not just futile but to result in the public and judicial pillorying and humiliation of complainants,

People talk about the evidence, and the evidence is overwhelming that the system has evolved to shield the male perpetrators of violence against women and children from being held legally to account for their crimes. It does this in countless systemic ways, that range from the way the authorities respond to sexual assault and abuse, to the basic attitudes and beliefs about women held by those in positions of power.

As Scaachi Koul put it in her brilliant deconstruction of the circumstances around the Ghomeshi case:

Women, and girls, and anyone who has ever had someone take a piece of their life away through sexual violence or harassment, knew the verdict wasn’t going to go our way because the system wasn’t even built for us. It was built for the men it protects, the ones we try to expose. Men who are accused of assault get a fair trial, but the women who accuse them are the ones who actually have to fight to protect their reputations.

As was noted in 2014 in The Globe and Mail:

It’s a crime like no other. A violation of the self as well as the body – an assault on trust, on privacy, on control. It’s also an offence with an afterlife: a sense of bruising shame and guilt.

And it happens to women in Canada every 17 minutes.

Some of those women place calls to services such as the Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter — about 1,400 of them last year alone.

“These are not just women who live in poverty or need,” says Summer-Rain Bentham, one of the counsellors who answers their calls. “These are women who are teachers, doctor or lawyers; women whose husbands may be police officers or judges.”

But if these women are hoping for more than support – if they are hoping for justice – the phones might as well keep ringing.

Less than half of complaints made to police result in criminal charges and, of those charges, only about one in four leads to a guilty verdict.

Women know this. Which explains why, according to the best estimates, roughly 90 per cent of sexual assaults, even those referred to crisis lines, are never brought to the attention of the authorities.

Queen’s University law professor Pamela Cross, an expert on sexual assault, says that if someone she knows personally were attacked, “I would advise thinking very hard” before calling the police.

A survey by Justice Canada itself found “that two-thirds of the men and women who took part had no faith in the justice system, the process of filing a complaint against their abuser and the prospect of seeing a conviction.”

This history of injustice towards women and sexual assault victims — a crime the perpetrators of which are 98% male — exists and has to be taken into account when one looks at the Ghomeshi case. As one woman commented in a thread I saw on Facebook, “The disbelief of women is historical and deep and has little to do with these particular complainants.”

The whole system is stacked against sexual assault victims from the second they even try to report and we have seen this time and time again.

Ghomeshi was known for his behaviour widely for years and was institutionally protected at the CBC due to his power and stature. He has been protected again by the justice system. It is widely known that there are many, many more victims.

No one with an ounce of intellect actually thinks that everyone who has publicly or anonymously said that he assaulted them could all be lying in some vast conspiracy. Anymore than anyone actually believes Bill Cosby is innocent. As Now Magazine put it, “Does anyone really believe that Jian Ghomeshi did not assault those women?”

And yet Ghomeshi is acquitted. And yet the crown, the judges and the courts fail yet again. And yet a justice writes a judgement eviscerating the victims.

This outcome, this result of a profound and deep systemic injustice, this product of a system designed by and within the power structures of patriarchy, this is part-and-parcel of our society’s history of violence towards women and girls.

This is the real issue that needs to be confronted

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.