A lot happened in 2019 in the world of politics and culture. The climate crisis got worse and youth around the world fought back, while the federal election sparked talk of Western Canada’s disillusionment with Justin Trudeau. The backlash against #MeToo demonstrated how hard it can be to enact systemic change, while the impeachment inquiry into Donald Trump revealed that the system of American democracy is less stable than everyone thought. Our staff’s top reads from this year touch on all of these important issues and more. Read on to find out rabble’s favourite books from 2019 and then tell us yours in the comments!

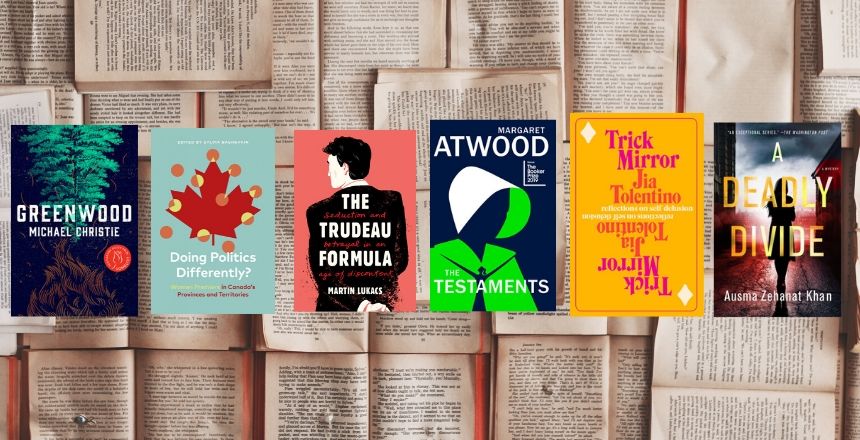

1. The Testaments by Margaret Atwood (Penguin Random House)

In Margaret Atwood’s long-awaited sequel to 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale, we are offered a taste of resistance. After over 30 years and seemingly endless political turmoil almost lending itself as reference to the book, I was very curious as to what the next chapter had in store. And I was pleasantly surprised that the story not only managed to build seamlessly on the first book, but was able to step beyond the grim narrative and offer a tale of agency and hope. In a time of chaos and the rise of the right, this is what we need.

– Tania Ehret, operations coordinator

2. Doing Politics Differently? Women Premiers in Canada’s Provinces and Territories edited by Sylvia Bashevkin (UBC Press)

Like a lot of people, I like to believe that women bring a different sensibility and ethic to life in politics. But there’s always the nagging question… what about Margaret Thatcher? Doing Politics Differently explores this question by looking at the careers of all 11 female premiers in Canada’s history. The wide range of the political spectrum is represented from Rachel Notley’s NDP government to the divisive politics of Quebec’s Pauline Marois and Christy Clark of British Columbia. The book doesn’t so much answer whether women do politics differently. Rather, it presents the question and invites the reader to draw their own conclusions based on each author’s considerable research. And that’s a useful start.

– Victoria Fenner, executive producer of the rabble podcast network (listen to Victoria’s interview with Bashevkin here).

3. Greenwood by Michael Christie (McClelland and Stewart)

The direct and terrifying link between climate change and deforestation lies at the heart of Michael Christie’s sophomore novel, which was longlisted for the 2019 Giller Prize. It begins in the year 2038, after a mysterious epidemic has destroyed most of the planet’s trees, sending the global economy into a tailspin. From there, Greenwood travels back to previous historical moments when humans had to pay for their environmental hubris: the 2008 financial crash; the 1970s energy crisis; the Great Depression, and the First World War. The story is told through a single tree-obsessed family, the Greenwoods, a different member of which features in each time period. What makes Christie’s novel so fascinating is the plot’s arborescent structure: it explores the Greenwood “family tree” by travelling back in time through different “rings” to the very centre of the story. What this suggests is that, while healthy forests are central to our physical survival on this planet, trees are also key to our imaginative wellbeing: they influence how we think about family, time, love, history and responsibility.

– Christina Turner, assistant editor

4. A Deadly Divide by Ausma Zehanat Khan (St. Martin’s Press/Minotaur Books)

There were many excellent books published in Canada this year, but A Deadly Divide stood out for me. Khan brings her sophisticated mystery skills to a new level by diving into the complex issue of identity, culture, Islamophobia, the rise of hate and right-wing movements in Quebec. Khan is a powerful storyteller. She brings strong male and female characters, fast paced narrative and plots twists that draw you in from the very beginning. A Deadly Divide takes on contemporary headlines and harrowing events to bring meaning and empathy to issues of Quebec identity and questions that we all need to grapple with in Canada. She calls out institutions (police, media, politicians and organized religion) for their roles in sowing division and seeks a path to healing.

– Kim Elliott, publisher

5. The Trudeau Formula: Seduction and Betrayal in an Age of Discontent by Martin Lukacs (Black Rose Books)

The Trudeau Formula is probably the best analysis of what Naomi Klein refers to as the “inner logic” of the Trudeau government that I’ve read. It takes a broad look at issues such as growing income inequality, environmental degradation and relations with Indigenous communities and compares the promise of “sunny ways” against what that looks like in reality. Whether it’s squandering billions on an aging pipeline or failing to deliver on proportional representation, Lukacs understands that it’s not always possible to govern the way that one would wish. The heartbreaking failure to have a meaningful relationship with Indigenous peoples, as promised during the 2015 election campaign, is seen by many as a fundamental betrayal and no doubt contributed to the Trudeau government’s failure to win a majority during the 2019 federal election. Launched just prior to the October election, The Trudeau Formula serves as both a cautionary tale and an analysis of exactly whose interests our government serves.

– Meg Borthwick, babble moderator

6. Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion by Jia Tolentino (Penguin Random House)

Jia Tolentino’s book is a standout among the collections of cultural criticism I read in 2019. The essays explore the various ways identity and discourse get refracted then distorted in the “trick mirror” of late capitalist, social media-fuelled culture. Tolentino unpacks the push toward constant optimization for women, the roots of the wedding industrial complex and the structures underpinning the operation of rape culture at the University of Virginia. The essay “The Cult of the Difficult Woman” is one of the most insightful analyses I’ve read recently of how the American right has weaponized popular feminist discourse and watered down feminism in the process. Tolentino’s own positioning in the systems she criticizes at times seems unsettled, even compromised, but it’s used to inform her writing, which is consistently revelatory and thoughtful.

– Michelle Gregus, outgoing managing editor

Background image: Patrick Tomasso/Unsplash