This is an address I gave at Queen’s University on Nov. 11, 2010. It remains the truest thing I can say about how to take progressive meaning and anti-war value out of a holiday remembering those who serve in national militaries. I’d be grateful if you gave it a read and let me know what you think.

“Good Morning.

I was very grateful that Brian asked me to speak today. It is a privilege to speak to you on this important occasion when we demonstrate, and contemplate, our remembrance of the great Canadians who have risked their lives in pursuit of the principle of freedom and to defend the vulnerable of the world.

I thought for a long time about how to start my speech, on such a solemn topic as Remembrance Day. I decided to begin by relating my family history and remembrance of war, and what this has meant to me in terms of being a citizen of Canada.

My grandfather served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and during the second world war he trained pilots who went overseas to fight. His father, my great grandfather, served overseas in the Second World War. Among my earliest memories, I recall that my mother held for me in trust an inheritance from her father – an old, cracked pine cigar box. Inside was a green beret, and an old army pay book, the pages stiff and yellowed. There was also a postcard from overseas, with a picture of my great-grandfather standing proudly in uniform. Finally there were the various medals collected from both of their services. All of these contents were folded neatly and solemnly, put aside for posterity and for my eventual remembrance of what my forefathers did. From childhood, I looked at them often enough, and heard the story from my mother: of how generations of brave Canadian boys took upon themselves the burden of justice, peace and freedom in defence of the defenseless. As Canadian citizens, they knew that they benefited from the security, freedom, and rights to which they were entitled here at home. They recognized a responsibility that came from this privilege: to defend those who were vulnerable; those who by nothing more than accident of birth were in a situation that denied them the rights they deserved. In World War II, forty two thousand, seven hundred eighty nine Canadians made the ultimate sacrifice for that principle, while a further ninety seven thousand nine hundred eighty eight were wounded. That is a sacrifice beyond my understanding, and one that makes a big impact on me. But Above all else, the imprint left on me by this astounding sacrifice is the moral principle resounding through the war journals and correspondents of the time – of the absolute necessity of defending the abused of the world.

When I thought about this childhood memory, it became clear to me what I wanted to say today. I want to celebrate my grandfather’s life in honour of that spirit of responsibility to the vulnerable and recognition of the privilege we enjoy as Canadians. That’s what my grandfather believed very deeply andvery truly about the role of the Canadian Armed Forces and it is in his honour, and honor of the principles he cherished, I want to speak.

A central concern of my talk today is how to honor the principles for which my grandfather and those many other brave Canadians stood? In my grandfather’s time, it was clear as day what the right course of action was. There was no guess work; people knew then, as we know now, that a war machine bent on genocide and domination had to be stopped. The only question was whether we would have the fortitude to sacrifice our own comforts and take up our responsibility to defend the weak. Today, the line between right and might is thinner. We know there is no clear and obvious moral compass to which we can look for our direction. In spite of this confusion, a perception that remains powerful is that the world has left an era of great conflicts and entered an optimistic, if still incomplete, time of development, growth, and reconciliation of the injustices of the world.

But this is less the case than we may at first realize, and the era of order is less orderly and far less just than it seems at first glance. Today, it’s true, the massive professional armies of the developed world no longer clash against one another on the battlefield. But, according to the United Nations Human Security Report, although the size of armed conflicts has gone down the deadliness of these conflicts is at a level never before seen in human history. The wars are fought in guerrilla style, in cities, civilian casualties and injuries are atrociously high, and the weapons are of a brutal efficiency. And the human costs of war are overwhelmingly born by the people of the so-called ‘developing world’. The armies of the developed world have an unprecedented technological ability to create death: from a facility in the continental U.S., a smart bomb can be virtually guided to its target, delivering its ordnance (as they call it) with accuracy and without any risk to the person of the one at the controls. The villages and towns of Iraq have been razed by these missiles, or by high-altitude bombers, for about twenty years without respite.

There is great political and social violence being done which call on that principle symbolized in my Grandfather’s medals. For another example, In Colombia in the last 2 decades, over 2800 trade unionists have been murdered by the state security forces, while the bulk of the military budget goes towards defending US oil pipelines and aiding the US war on drugs. Or, Under Pinochet’s regime in Chile, thousands upon thousands of people were tortured, murdered or disappeared. It is now openly admitted that the CIA aided the Coup that brought Pinochet to power, and supported the regime. Henry Kissinger wrote to Pinochet, “In the United States, as you know, we’re sympathetic to what you’re trying to do. We wish your government well”. Henry Kissinger won a Nobel Peace Prize.

Knowing these facts, if I want to honour my grandfather’s principles and his memory – what must I say? I believe he would have a lot to say about several things that , in today’s fragmented world, are left unsaid. He would certainly speak up about the continuing violence done to the First Nations of Canada, who are plagued by disproportionate poverty, crime and incarceration, poor health, and who are disproportionately also the victims of violent crimes. He would speak against the alarming numbers of “missing” indigenous women. He would be saddened by the loss life of hundreds of Aboriginal Canadian women have disappeared, never to be seen again. The first nations of Canada certainly constitute an abused group in the world, for whom my grandfather would feel the responsibility to stand up.

My grandfather would have also had a lot to say about atrocities committed the world over; for example he would have likely approved and even honored Romeo Dallaire’s moral stance on the Rwandan Genocide. In Rwanda, as an ethnic genocide intensified, Dallaire was unable to get the reinforcements he requested in order to protect the victims. Nevertheless, he and the staff available to him created areas of ‘safe control’. Their actions in that conflict are directly responsible for saving the lives of 32, 000 people. But at the same time My grandather would have been troubled by the international silence on Palestinian Human Rights. He would have recognized the injustice of desecrating Palestinian Towns, orchards and ancient sites. He would have been angered by the death of Palestinian civilians. He would have been dismayed by the following order, issued by the Israeli Defense Force’s central command to its soldiers: “when our forces encounter civilians during the war or in a raid, the encountered civilians may, and even must, be killed. Under no circumstances should an Arab be trusted, even if he gives the impression of being civilized”. The world is constantly plagued by many conflicts and injustices just like this one, and on remembrance day, I am inspired by the example of Romeo Dallaire’s act of solidarity; his willingness to speak truth to power, even while incurring personal and professional risks. I think his is a model we have to aspire to.

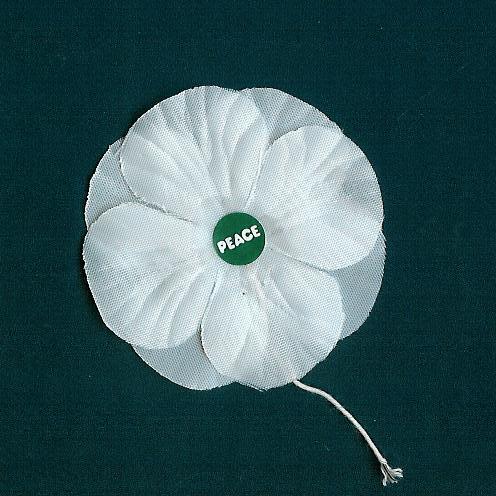

Remembrance Day is a time to honour and remember the nobility of the principles defended by the brave citizens of Canada who have come before us. To honour those principles today, I think, requires us to recognize and stand against the atrocities committed at home and abroad. Because of what my grandfather did, I have a responsibility to carry forward the principles he stood for. So in closing, My message is that the confusing and violent nature of our times calls on us to do more on remembrance day than wear a poppy. In order to truly honour the sacrifices of those who fought for justice, we are now required to speak about new forms of injustice, perhaps ones that are harder to see, harder to recognize, that punctuate the lives of the many abused people of this planet. For my grandfather’s generation, the decision to live up to this responsibility carried many difficult burdens, perhaps foremost of which was the great sacrifice of personal safety and life given by so many thousands. Today, different circumstances and new knowledge may require other personal sacrifices. These may include the hardship of re-thinking our moral principles and assumptions, putting ourselves in unpopular or dangerous positions, and doing everything we can to force the powers of the world to change their notion of international policy, even justice. However, unless we rise to the challenge and do exactly this, we fail to honour the true legacy for which we have gathered here today.”