Reporting independently from the front lines of war is an increasingly rare engagement for journalists working for major international media outlets. From Iraq to Afghanistan, reporters are increasingly embedded with Western military forces, operating without independence.

When Israeli military forces launched an invasion into the Gaza Strip, international journalists were barred entry into the territory by the Israeli government for the majority of the conflict, despite a ruling from the Israeli Supreme Court that called on the government to allow international reporters into the territory. Major international media outlets, including CNN and the BBC, ended up reporting from hilltops in Israeli-controlled territory kilometres away from the actual conflict.

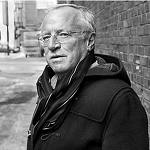

British journalist Robert Fisk has offered fiercely independent accounts of conflicts throughout the Middle East for decades. Stationed in Beirut, Lebanon, Fisk reports for the UK-based Independent newspaper and is widely read around the world. Fisk spoke with community activist and journalist Stefan Christoff about the media response to the recent war on Gaza.

Stefan Christoff: Historical context is often not included in daily reporting on the Middle East. Could you offer some historical perspectives to the recent war in Gaza?

Robert Fisk: In 1948 when the Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes — 750,000 is the figure widely accepted — those in the north in the Galilee area of what became Israel fled into Lebanon, those in the Jerusalem area fled east toward what we now call the West Bank and those in the south fled into what we now call the Gaza Strip.

For example, in 2000, after the Israelis finished their final withdrawal after 22 years of occupation and went across the border back into Israel, many Palestinians in Lebanon went down to the border and looked across, not because they were looking at northern Israel but because they were looking at the northern part of Palestine as they had known it – some could actually see the villages that their parents or grandparents had come from in 1948.

So there is this whole Diaspora around the state of Israel who can’t go home because their home is on the other side of the border. This reality revolves around the whole issue of UN General Assembly Resolution 194 on the right of return, [which stipulates that] these Palestinian refugees have the right to return to their homes.

Well over half the people living in Gaza are families, either survivors or descendants of Palestinians who lived only 10 or 12 miles into what is today Israel. So when you hear the Israelis say the terrorists are firing rockets into Israel, the Palestinians in Gaza can say in many cases, ‘Well, my grandson is firing a rocket at my town because before 1948 these areas would have been Palestinian property.’

SC: Can you talk about your perceptions of media coverage on the latest war in Gaza?

RF: There were two things that happened. First, the international press allowed for their own humiliation: Israel told the press that they couldn’t go into Gaza and they didn’t really try to, so the press sat outside Gaza and pontificated from two miles away. Israel wanted to keep the international press out of Gaza and they were kept out, that was that.

It is instructive to note that no major Western media outlet had a reporter based inside Gaza who would have been there when it started. Clearly, after the kidnapping of a BBC reporter, who was based in Gaza, it is not surprising that the international news agencies were hesitant to base reporters there. However, it is also instructive to note that it was the Hamas government that had the BBC reporter released, which is not often mentioned now.

SC: So what kind of more widespread effect did the reporters who were left in Gaza have on Western media?

RF: Faced with the fact that the only journalists left inside Gaza were Palestinian reporters, the major networks were forced to hand over their reporting to Palestinian Arabs, who in many cases were refugees inside Gaza. This meant that you had Palestinian reporters on the ground talking about their own people, unencumbered by Western reporters cross-questioning them or trying to put 50 per cent of the story on one side and 50 per cent of the story on the other side.

Al Jazeera came out as the heroes of journalism because they had their international service, their English service and also their Arabic service fully operational from offices inside Gaza. Individual Palestinians working for Western news organizations showed that they could be competent journalists, and the Western journalists who sat outside Gaza looked as pathetic as their reporting on the Middle East is becoming.

Palestinian reporters were telling their own stories, in the case of [the Independent‘s] Palestinian reporter inside Gaza, his father was killed in an air strike, his father, who was a pro-Palestinian Authority, English-speaking, well-educated judge, was killed in his orchard. So the Independent had on our front page this terrible and tragic story of this innocent man destroyed, atomized into pieces of flesh by an Israeli air strike on his orchard, a story reported by his own son in our newspaper.

So this was the kind of journalism from Palestine that we hadn’t seen in the major [Western] press, so there was an upside to the [international] press being banned from Gaza. However, the work of the international reporters was truly pathetic.

Stefan Christoff is a community organizer and journalist based in Montreal.