One of the more contentious issues regarding the B.C. government’s record concerns the issue of social housing. To hear Minister Rich Coleman tell it, B.C.’s record has been above and beyond. For the last few years, barely a week has gone by without a government news release (sometimes multiple per week) trumpeting a new housing initiative.

Yet many housing and homelessness activists insist the need for low-income housing outstrips new supply, and even the most astute observers of the housing file find it difficult to determine which government announcements are new and which are recycled; which deal with actual new housing, and which merely capture conversions of one kind of housing into another. Much of the time, tracking the housing file feels akin to watching a talented sidewalk magician asking us to follow which shell has the ball.

The trick to cracking this puzzle is to look to the government’s own numbers; not those in the government news releases or Minister’s statements, but rather, the numbers contained in the much more dry annual BC Housing Service Plans.

That’s precisely what the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Social Planning and Research Council of BC did back in 2010, when we teamed up to issue a report that sought to make sense of the housing numbers. Unpacking the Housing Numbers, co-authored by myself and Lorraine Copas, tracked five years of BC Housing Service Plans to determine how much new social housing was actually brought on stream between 2006 and 2010.

The picture that emerged was mixed, but on balance, very troubling. As the number of homelessness B.C. residents escalated for much of the last decade and public concern mounted (and perhaps more cynically, as B.C. prepared to welcome the world to the 2010 Winter Olympics), there was indeed a great flurry of activity on certain fronts. But most of that activity did not represent actual new social housing. Most of the increased government support was focused in three areas: rental assistance supplements, new emergency shelter beds, and the purchase of a number of existing single room occupancy (SRO) hotels. While these initiatives were needed and laudable, for the most part they did not represent an actual increase in the stock of low-income affordable housing.

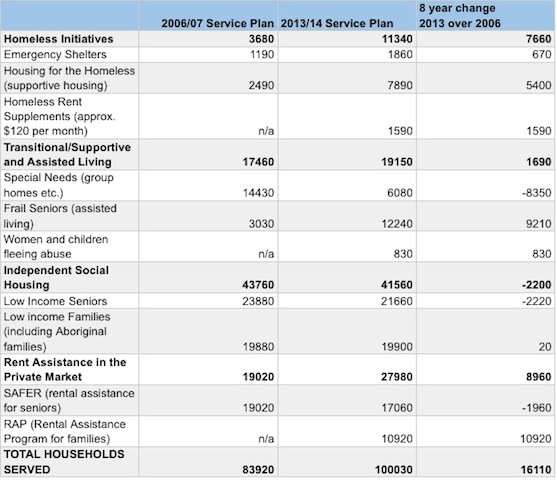

We now have three more years of data from BC Housing Services Plans, so I figured it was time to revisit the numbers and see if anything has changed since 2010. The table below summarizes the total households assisted, comparing 2006/07 and plans for 2013/14.

Table: BC Housing Initiatives, Households Assisted by the Continuum of Housing and Support Services, 2006-2013

Source: BC Housing Service Plans, 2006/07 through 2013/14

Unpacking the numbers

So, what do these numbers tell us? The government is pleased to tout that in the year to come, it will provide housing assistance of some form to more than 100,000 B.C. households, an increase of 16,110 households since 2006.

But note the following. Of the 16,110 increase:

– 10,550 (or 65 per cent) of this increase has been in the form of rental assistance (mostly due to the new Rental Assistance Program for families with children combined with a smaller amount in rental supplements for the homeless, offset by a small decline in rental assistance for seniors). Such programs may indeed be valuable to some families, but they do nothing to create new low-income housing stock (and offer nothing to families on social assistance or single people, who are excluded from the program). And the low take-up rate for the RAP indicates that most low-income families have not been adequately encouraged to access the program.

– 670 of the increase was in more emergency shelter beds (such as Vancouver’s HEAT program). Again, this has been needed, but it’s not housing.

– There has indeed been an notable and positive increase in housing for the homeless, with supportive housing for homeless people dealing with addiction and mental health challenges increasing by 5,400 units. However, 1,550 of these units are in SRO hotels that the province purchased in order to protect them from demolition or conversion into more expensive housing, with the goal of placing them under non-profit management. Again, purchasing these hotels was a good policy decision, but it means that the net new units in this category came to only 3,850.

– Transitional supportive housing increased by 1,690 units, but this is offset by a loss of 2,200 units in the independent social housing category (what we traditionally think of as social housing for low-income households). Much of this stems from regular social housing for seniors being converted into assisted living, and thus switching to a different category. Also notable is a sharp decline in special needs housing (such as group homes). The introduction of housing for women and children fleeing abuse is likely not new, but rather, simply a product of shifting administrative authority for these units from the Ministry for Social Development to BC Housing.

– Noteworthy as well is that, in all this time, there has been virtually no change in the stock of basic social housing for low-income families.

Overall then, after accounting for the points above, what the government’s own numbers tell us is that over the last eight years, B.C. has seen an actual net increase of approximately 3,340 new units of social housing, or 418 new units per year.

That’s a notable improvement over what we found in our 2010 report; the last three years in particular have seen a sizable jump in supportive housing come on stream, as long promised new buildings have finally reached completion.

Low by historic comparison

However, 418 units per year of new social housing stock is nothing to boast about. By comparison, between the mid 1970s and the early 1990s, with joint funding from the feds, B.C. used to bring on stream between 1,000 and 1,500 new units of social housing per year. And if one includes the widespread co-op housing construction in that era, the number of new units created in the province was closer to 2,000 per year. B.C. still benefits from the legacy of that period; thousands of families and individuals have relied on this low-income housing stock at one time or another, depending upon it to make a better life for themselves and their children. We have all been greatly assisted by the ambitious plans and visions of earlier governments.

After the federal government ended funding for social housing in 1993, B.C.’s NDP government at the time continued to build new social housing, but in the absence of money from the feds the pace of construction slowed. And during the B.C. Liberal government’s first mandate (2001 to 2005) there was almost no new investment on the housing front.

It’s no great mystery then why by the mid 2000s homelessness had reached a new crisis level. As a society, we used to be considerably better at bringing new affordable housing stock on-line.

What now?

Of great concern now is that no new plans for building social housing are in the works. The February B.C. Budget only provided money for renovations for the decrepit SRO hotels that have already been purchased by government. This must change, or in a few short years, the extent of the homelessness crisis will be right back to where it was before the 2010 Olympics.

Building social, coop and affordable housing is not a job that society can do once and be done with it. It must be an on-going commitment. Population growth means new demand will always materialize, and growing inequality and labour market polarization only exacerbates the need (as more and more people find market rents out of reach). If we are not continually increasing the stock of social housing, rising homelessness will be an ongoing fact of life in B.C., and piece-meal efforts such as rental supplements and shelters will constitute nothing more than a futile game of catch-up.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We have choices. Building 2,000 units of social housing, for example, costs about $400 million; an amount that could be raised if we introduced a new tax bracket at $150,000 of income at 18 per cent (as the CCPA modeled in our recent Tax Options report). Building 10,000 units a year (as the new BC Social Housing Coalition has called for) would cost about $2 billion; a lot of money to be sure, but equivalent to less than 1 per cent of BC’s GDP. Surely in a society is wealthy as ours, there is no need for homelessness.

This post has also appeared on the Tyee here.