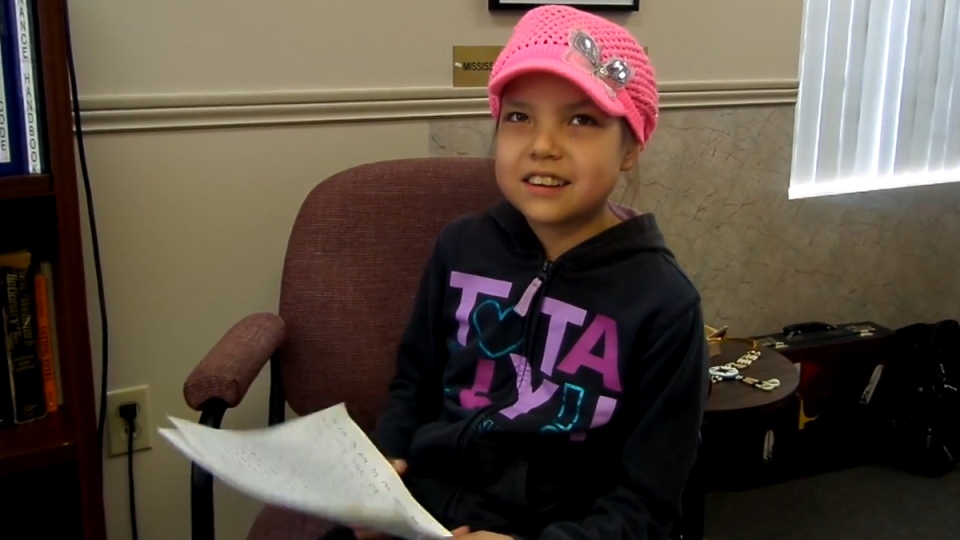

The tragic death of Makayla Sault — who died of leukemia after stopping chemotherapy — has triggered a backlash. “First Nations parents can now doom their sick children,” warned the Toronto Star. “Dying, because her parents were likely weak and uninformed, possibly misled, and our institutions could not find the backbone to protect this child,” wrote an infuriated doctor in the Ottawa Citizen. “Just how Aboriginal rights should matter to any of this in the first place is something that beggars belief,” exclaimed the National Post. What beggars belief is the way in which these remarks ignore and reinforce colonialism.

Cancer, colonialism and capitalism

Makayla died from cancer, an invasive and destructive disease that colonizes the body and extracts its life force without its consent. This is what Canada has done to Indigenous peoples. As Indigenous academic Leanne Betasamosake Simpson explained,

“Colonialism and capitalism are based on extracting and assimilating. My land is seen as a resource. My relatives in the plant and animal worlds are seen as resources. My culture and knowledge is a resource. My body is a resource and my children are a resource because they are the potential to grow, maintain, and uphold the extraction-assimilation system. The act of extraction removes all of the relationships that give whatever is being extracted meaning. Extracting is taking. Actually, extracting is stealing — it is taking without consent, without thought, care or even knowledge of the impacts that extraction has on the other living things in that environment. That’s always been a part of colonialism and conquest. Colonialism has always extracted the indigenous — extraction of indigenous knowledge, indigenous women, indigenous peoples.”

As a consequence of living in a system that treats people and the planet as mere resources, regardless of the toxic consequences, we’re in the midst of a cancer epidemic — with half of all people in Canada developing some form of cancer. This has been normalized (blamed on our genes or the natural aging process) or blamed on individual “lifestyle choices” like smoking. But much of the cancer epidemic is rooted in the economy that contaminates the earth, water, air and food on which we depend. The pollution of Indigenous territory from the tar sands has led to high cancer rates in Fort Chipewyan, and the carcinogenic economy also affects those on whose labour it depends.

As the Unifor Prevent Cancer Campaign explains,

“Workers in certain carcinogenic-laden industries are contracting cancer at rates well beyond those experienced by the general population. At last 60 different occupations have been identified as posing an increased cancer risk. Studies show that the auto industry is producing laryngeal, stomach and colorectal cancers along with its cars. The steel industry is producing lung cancer along with its metal products. Miners experience respiratory cancers at rates many times higher than the expected levels in the general population. Electrical workers are suffering increased rates of brain cancer and leukemia. Aluminum smelter workers are contracting bladder cancer. Dry cleaners have a elevated rates of digestive tract cancers. Firefighters contract brain and blood-related cancers at many times the expected levels. Women in the plastics and rubber industry are at greater risk of uterine and possibly breast cancer. The list goes on…Why do we hear so much about the dangers of tobacco but so little about the other 23 lung carcinogens? The reason is that tobacco is claimed to be a ‘lifestyle’ choice, so industry and the medical profession can blame the victims. The other 23 known causes of lung cancer are related to industry. They can be prevented and removed from our workplaces and our environment.”

Colonial medicine

Colonization has included medical arguments and institutions. As the physician and philosopher Frantz Fanon wrote in A Dying Colonialism,

“The fact is that the colonization, having been built on military conquest and the police system, sought a justification for its existence and the legitimization of its persistence in its works. Reduced, in the name of truth and reason, to saying ‘yes’ to certain innovations of the occupier, the colonized perceived that he thus became the prisoner of the entire system, and that the French medical service in Algeria could not be separated from French colonialism in Algeria.”

The same is true in Canada. As Laurie Meijer Drees writes in Healing Stories: Stories from Canada’s Indian Hospitals, “As early as 1914, sections of the Indian Act allowed the government to apprehend patients by force if they did not seek medical treatment.” This forced treatment denied traditional medicine and included segregated facilities (“Indian hospitals“) that medically experimented on Indigenous people. The same happened in residential schools that stole Indigenous children from their communities — a practice that continues today through other means.

The denial of traditional knowledge included imposing a highly restricted view of healthcare (“Western medicine”) that reduces health to an isolated individual and pharmaceutical intervention — ignoring social, economic, environmental and cultural factors that determine health and the accessibility and effectiveness of pharmaceuticals. There’s nothing inherently Western about this biological reductionism. In his 1845 work Conditions of the Working Class in England, Friedrich Engels outlined a social model of health, and called diseases “the necessary consequence of the present neglect and oppression of the poorer classes.” But a biological reductionist view came to dominate capitalist healthcare — undermining the potential of its own treatments, by ignoring broader factors that shape people’s susceptibility to illness and their potential to access and benefit from medication. Profit-driven pharmaceutical corporations dominate healthcare, creating skepticism and reinforcing a market in equally profit-driven “alternative” medicine like the Florida clinic that treated Makayla.

Right to refuse, and right to access

Given the legacy of colonialism it’s not surprising there might be suspicion towards hospital treatment — especially when accompanied by threats of apprehension, in order to enforce such a difficult regimen as chemotherapy (despite its effectiveness in treating leukemia). We might disagree with the choice to stop chemotherapy, though Makayla did brave it for nearly three months before stopping it (contrary to media headlines that she simply refused it). But as the courts found, “(Makayla’s mother’s) decision to pursue traditional medicine for her daughter is her Aboriginal right. Further, such a right cannot be qualified as a right only if it is proven to work by employing the western medical paradigm. To do so would be to leave open the opportunity to perpetually erode aboriginal rights.”

Despite media claims, “Indigenous rights versus Western medicine” is a false dichotomy. While Makayla died after stopping treatment, there are far more Indigenous people who die from being denied access to treatment and prevention — and this sparks far less fury from the mainstream media. “Racism can doom sick patients,” could have been the headline after Brian Sinclair died in a Winnipeg ER, denied treatment for 34 hours. “Our institutions could not find the backbone to protect this community,” could be written about the Ontario government’s refusal to support the community of Grassy Narrows against mercury poisoning. “Cancer rates in Fort Chipewyan beggar belief,” should be included in every discussion of the tar sands.

If we’re concerned about private clinics profiting from dubious claims and treatments, then the response should not be to blame Indigenous families who chose that option. Instead we need to strengthen public healthcare, including creating a national pharmacare program and stopping Harper’s $36 billion cut to health care (and the federal government’s denial of chemotherapy to refugees).

Decolonizing medicine

Thanks to Indigenous sovereignty and solidarity movements there are growing attempts to decolonize medicine. As Brantford physician Chris Keefer wrote last spring in the Two Row Times,

“By behaving in a manner consistent with a colonial master’s mentality, McMaster Children’s Hospital and members of the medical team have very unfortunately created a lack of trust and a break in the therapeutic bond between the medical team and the family. Threats of apprehension of Onkwehon:we children, the dis-respect of elders in family meetings, and denigrating remarks about traditional medicines have no place in a respectful two row relationship. Such actions, comments and behaviours extinguish the opportunity to build trust with the family, trust that is necessary to encourage the family to pursue a very difficult two year treatment plan marked by severe and even life threatening side effects. As a medical doctor trained within Canadian society with no experience of traditional Onkwehon:we medicines, I am not sure that the family is making the right choice by refusing chemotherapy. However it is not my right as a member of Canadian society to impose my will upon Onkwehon:we people.”

The Canadian Medical Association Journal has taken the same progressive approach. In their article “Caring for Aboriginal patients requires trust and respect, not courtrooms,” Lisa Richardson of the University of Toronto Office of Indigenous Medical Education and magazine deputy editor Matthew Stanbrook write:

“Media coverage has fueled a narrative of polarized paradigms that is unhelpful and misleading, implying false choices. Medical science poses no inherent conflict with Aboriginal ways of thinking. Medical science is not specific to a single culture, but is shared by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people alike. Most Aboriginal people seek care from health professionals — but nearly half also use traditional medicines. Aboriginal healing traditions are deeply valued ancestral practices that emphasize plant-based medicines, culture and ceremony, multiple dimensions of health (physical, mental, emotional and spiritual), and relationships between healer, patient, community and environment. These beliefs create expectations that Aboriginal patients bring to their health encounters; these must be respected. Doing so is not political correctness — it is patient-centered care…For the state to remove a child from her parents and enforce medical treatment would pose serious, possibly lifelong, repercussions for any family, but such action holds a unique horror for Aboriginal people given the legacy of residential schools. To make medical treatment acceptable to our Aboriginal patients, the health care system must earn their trust by delivering respect.”

At the same time we can learn from Indigenous teachings to broaden our conception of health and healthcare. As the National Aboriginal Health Organization explains, health indicators include not only individual lifestyle behaviours like smoking and physical activity, but also health knowledge, personal resources, health services (both access to physicians and Aboriginal representation in health professions), physical environment, and social and economic environment. Rather than blaming a family for their tragedy, we should be collectively working to improve these determinants of health, so that we can treat and prevent cancer and replace the cancerous system driving it with one that respects people and the planet. As the Six Nations of the Grand River and the Mississaugas of the New Credit explained “We sincerely hope that this decision is part of an emerging era of healing and reconciliation between Canada and our nations. We hope that our children and generations to come will no longer experience the mistrust, misunderstanding, and mistreatment by the Canadian government that have been our daily reality for over 200 years.”