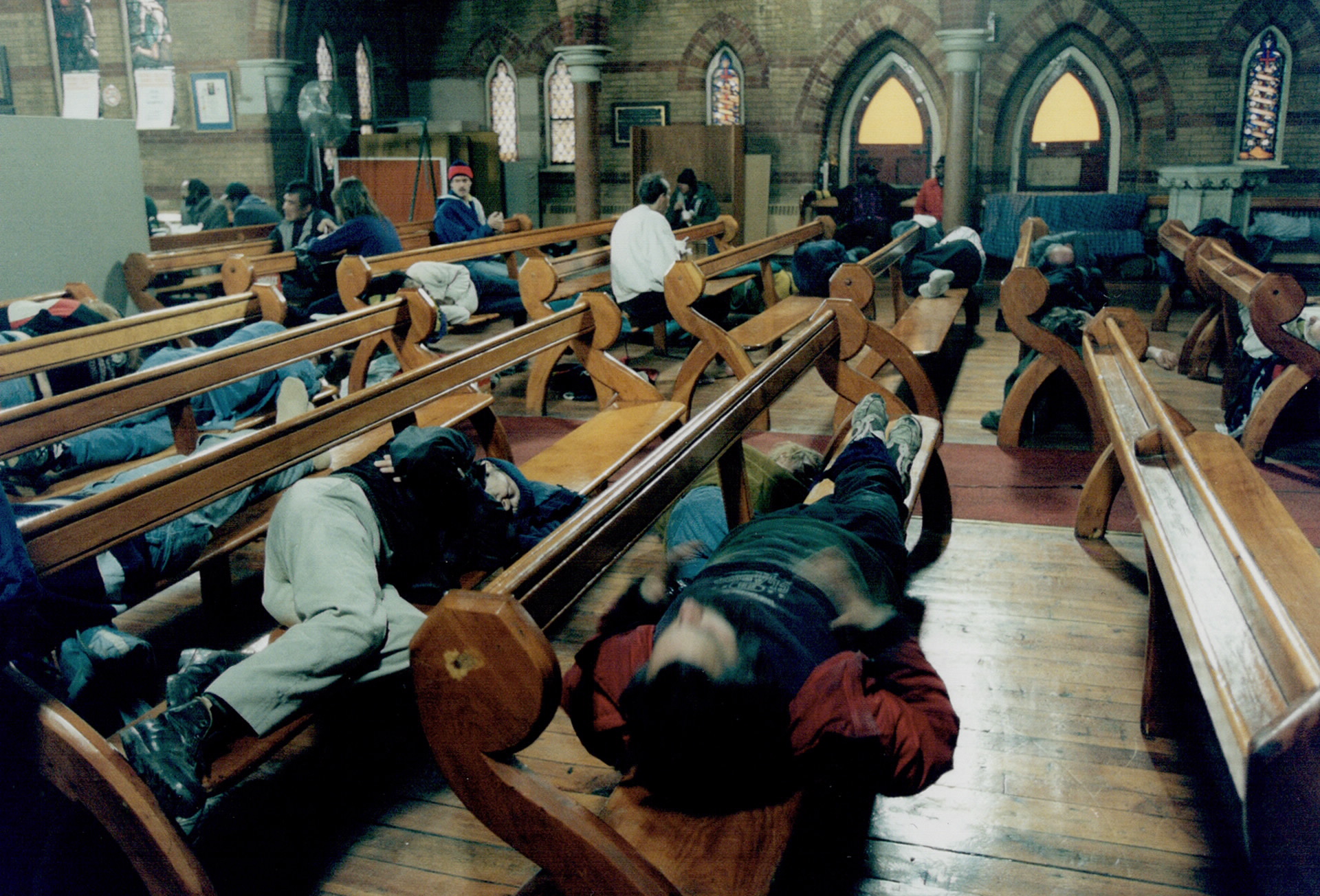

It is Wednesday evening, December 13, and the city has declared a cold alert for the third consecutive day. Temperatures are expected to drop down to -18 degrees Celsius, -26 with the wind chill. Tonight, a record 468 people will make their way to Toronto’s four warming centres, three Out of the Cold programs, and two 24-hour drop-ins for women. Situated in the heart of “skid row,” All Saints Anglican Church, which houses one of four warming centres, will shelter close to 100 people. Margaret’s Toronto East Drop-In Centre staffs the warming centre, and they have rented the parish hall at the back of the church and the larger portion the nave (sanctuary) at the front of the church, too. Mats will be handed out, along with a blanket to those lucky enough to get them. Others will simply find a space on the wooden floor. Temperatures inside the nave go down as low as 14 degrees Celsius, meaning that most people will sleep fully clothed and with their winter coats on to try and stay warm.

At 6 a.m., homeless men and women who have spent the night in the nave are being woken up. Lights are turned on. Staff start gathering up the mats and blankets. Those who are too slow to wake up are warned that they will be barred. Angry words are often exchanged between staff and the tired homeless during this period as they reluctantly give up their mats and blankets. Once this morning ritual is completed, many people simply lie down on the wooden floor and go back to sleep, others sit on chairs half asleep. Many scramble to find one of two toilets made available to them. A third toilet has a note on the door: “Out of Service.” A few days earlier the one sink that enabled people to wash their hands was out of service.

Some of the people venture into the cold winter weather and make their way to the back of the church where breakfast is being served. Often there is not enough food to feed everyone. The 24-hour warming shelter is emptied for a few hours during the day so that the floors and washrooms can be cleaned. The Parish Hall is the first to be cleaned.

The 40 to 50 homeless men and women are forced to leave with their belongings between 1 p.m. and 2:30 p.m. Most make their way to the front of the church and tensions rise during this period as more people are crammed into the church. At 2:30 p.m. people are again kicked out for an hour and forced to gather their belongings in order for the front of the church. They now make their way to the Parish Hall. Tension is very high during this period and fights often break out and police have to be called. Some homeless are barred for long periods of time. Hidden behind the doors of All Saints Church is the long history of the abandonment of Toronto’s poor by all three levels of government. By 8 p.m. in the evening, mats and blankets are once again handed out and people begin to stake out a piece of the church floor where they will spend the night.

All Saints Church remains one of the most important landmarks in Downtown East Toronto. First built in 1874 for $15,000, with the land purchased for $2,000 two years earlier, the property is now worth millions of dollars. Developers and speculators have been circling the old church like vultures for decades.

In its early years, All Saints’ affluent parishioners included Sir John A. Macdonald and Senator George W. Allan, a close friend of the church’s first rector, Rev. Arthur H. Baldwin. Robert T. Gooderham and Samuel Trees, important businessmen in the city, attended the church as well. However, after World War I and throughout the Great Depression, many of the church’s wealthy parishioners left the area. All Saints, which had fallen on hard times, was struggling to maintain the building in the late 1960s. The Anglican diocese had rejected a proposal to amalgamate with St. Luke’s United Church, located a few blocks north on Sherbourne Street. The proposal, which called for the demolition of the aging church, was rejected by just a few votes.

By the time the new rector, Rev. Norman Ellis, arrived at All Saints Church in 1964, the parish consisted of 90 aging parishioners who lived outside of Downtown East Toronto. By now many of the industries that had been established from the 1850s onwards had disappeared, along with the jobs that they provided. The old Victorian homes that once housed the wealthy were now rooming houses and flop houses for the area’s poor. By 1970 there were 3,000 rooms and 500 flop houses located in South Carlton. Seaton House, Canada’s largest men’s hostel, had relocated to George Street, just a few blocks from All Saints. Two thousand hostel beds within a three-block radius of the church were filled every night. Rev. Ellis would later write how he “crash-landed on skid row.”

Rev. Ellis was an advocate of the social gospel movement, which believed that Christians should be more responsive to social problems. He began to challenge the old middle-class values of the diocese, which he argued had kept the poor from entering the church. These old prejudicial attitudes dated back to the early days of All Saints when Rev. Baldwin and Senator Allan were trustees at the House of Industry. Both men advocated for a labour test, which was introduced at the House of Industry in the 1890s, that made it mandatory for Toronto’s unemployed to break stone in return for shelter and food. As Rev. Ellis toured various dilapidated areas of the church he saw a notice board in the gym with the grim caption: “THE WAGES OF SIN IS DEATH… EVERYBODY WELCOMED.” Rev. Ellis understood why the church had failed to bring in the poor.

In 1971, All Saints was de-established and the church was turned into a community centre that offered a range of programs to the poor, including an overnight shelter. Programs also included two large drop-ins and a Rooms Registry. Lawyers from a local legal clinic set up workshops, mental-health workers worked with psychiatric survivors, nurses set up health clinics, and First Nations people set up support services for the Aboriginal community. Rev. Ellis estimated that during its peak time the church would have had up to 40 workers coming in and out of the community centre. Established social agencies such as Street Health and Council Fire started out of All Saints Church.

Rev. Ellis, who wrote two books about his experience at All Saints, described the significance of the moment when All Saints was de-established and opened its doors to the poor:

“It was when we opened the church and other buildings as a church-community centre day and night and the masses of poor, homeless, the drunks, and the prostitutes, poured in, that, then, I believe, Christ entered with them, and wondered perhaps why we had left Him out in the cold so long.”

By the mid-1980s, a poor people’s organization was using the church to organize protests to address systemic social issues. The Toronto Union of Unemployed was organizing around the lack of housing for single adults, roomers’ rights, overcrowded shelters, and the freezing death of a homeless woman, Drina Joubert.

In the mid-1990s, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty was meeting in All Saints to organize against draconian welfare cuts, the lack of housing, and conditions in the overcrowded shelter system. In the summer of 1996, the Toronto Coalition Against Homelessness, which had formed after the freezing deaths of three homeless men, held an inquiry inside the church to investigate living conditions in the shelters. In the fall of 1998, a few weeks before Toronto declared homelessness a national disaster, the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) gathered inside All Saints to protest the death of three homeless men. TDRC would later use the church to organize against the deteriorating shelter conditions and call for the federal government to build more housing.

The refusal of politicians to seriously address the city’s homeless crisis over the past four decades has led to a situation today where shelter occupancy levels run at well over the 90 per cent level that is deemed acceptable. Over the years, substandard bandage solutions have led to the creation of city-funded warming centres that have the homeless sleeping on mats, on church floors, and in overcrowded facilities that do not have sufficient washrooms and no showers. With the number of homeless using these centres now approaching the 500 mark, close to 10 per cent of the homeless who manage to secure a space in the shelter system sleep in spaces that do not meet the shelter standards. The federal government’s elimination of its Federal Housing Program in 1993, as well as cuts to welfare rates during Mike Harris’s Conservative government in the mid-1990s — rates that remain inadequate — have also greatly contributed to the current homeless crisis.

All Saints Church continues to offer respite to the homeless. Rev. Ellis testimony, however, provides us with an account of the conditions of the overnight shelter at All Saints decades ago, which eerily resemble conditions of the present day warming centres.

“During the winter and week-ends (Friday, Saturday, Sunday) this large hall is open as an ‘Over-Night Drop-in’ for people who have nowhere to sleep or who cannot afford a rooming-house, or who are barred from the missions — also for some who cannot bear to be in their room alone for hour after hour. We work in conjunction with the Salvation Army, Fred Victor Mission, and with the city hostel, Seaton House, and are supported by grants from the Metro Hall Social Services. Numbers vary from about 80 to 150. We have no beds, because we are not a hostel, so that the best we can offer are ‘moving pads’ to sleep on a very hard floor. It is a sad state of society that as many as 150 men sleep here in these conditions, when the other facilities of the missions filled to capacity.

It is unknown how long All Saints can continue to take in the poor. A few winters ago, it was forced to close its doors for several weeks after pipes froze during a cold spell. As the gentrification of Downtown East Toronto continues to intensify pressure will be put on the Anglican Diocese to sell the church. Over the years more and more people have been displaced from the area. The city’s homeless crisis shows no signs of ending.

In the 1990s and 2000s, when the city’s shelters were beyond capacity, the city asked the federal government to open the Fort York and Moss Park armouries to house the city’s homeless. Despite protests by anti-poverty activists, inter-faith groups, and social agencies calling on Mayor John Tory to open the armouries, he has refused to do so. His administration has also refused to boost shelter capacity enough to meet the needs.

When Rev. Ellis opened the doors of All Saints Church to the poor almost a half century ago, even he recognized the injustice of having 150 people sleeping on mats on a hardwood floor. The social gospel teachings that he practised and his interactions with the poor enabled him to see and understand the destitution that the poor were experiencing. The failure of today’s city politicians to acknowledge the homeless crisis and their failure to address the living conditions inside city shelters and warming centres will only contribute to more homeless deaths, serious injuries, and the spread of disease.

It is now midnight and the city’s cold alert continues to be in effect for the fourth day. Hidden away behind the doors of All Saints Church is the long history of the abandonment of Toronto’s poor by all three levels of government, and their failure and refusal to provide for some of the city’s most destitute residents.

Gaetan Heroux a member of the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty and co-author with Bryan D. Palmer of Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History.

Photo courtesy of Gaetan Heroux

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.