Guantánamo Bay, located on the southern tip of Cuba, is home to the notorious U.S. military prison known as “Gitmo,” where 779 men have been held, most without charge, and brutalized over the past twenty years. One of these prisoners, Yemeni-born Mansoor Adayfi, or “Detainee #441,” was held for 14 years, until 2016. He is now living in exile in Serbia, where the U.S. forced him to relocate despite having no connection to the country. Adayfi’s memoir has just been published. In it, he describes the horror of Guantánamo, and how he and his fellow prisoners maintained their sanity, built solidarity, and survived.

Adayfi spoke on the Democracy Now! news hour from Belgrade. He smiles and laughs throughout the conversation, despite having endured years of torture and arbitrary imprisonment. He picked up most of his nearly fluent English from the guards at Guantánamo. He described the remarkable diversity of the prison population into which he was thrust:

“Imagine around 50 nationalities, 20 languages, different backgrounds,” Mansoor Adayfi said. “People who were at Guantánamo were artists, singers, doctors, nurses, divers, mafia, drug addicts, teachers, scholars, poets. That diversity of culture interacted with each other, melted and formed what we call Guantánamo culture, what I call ‘the beautiful Guantánamo.’”

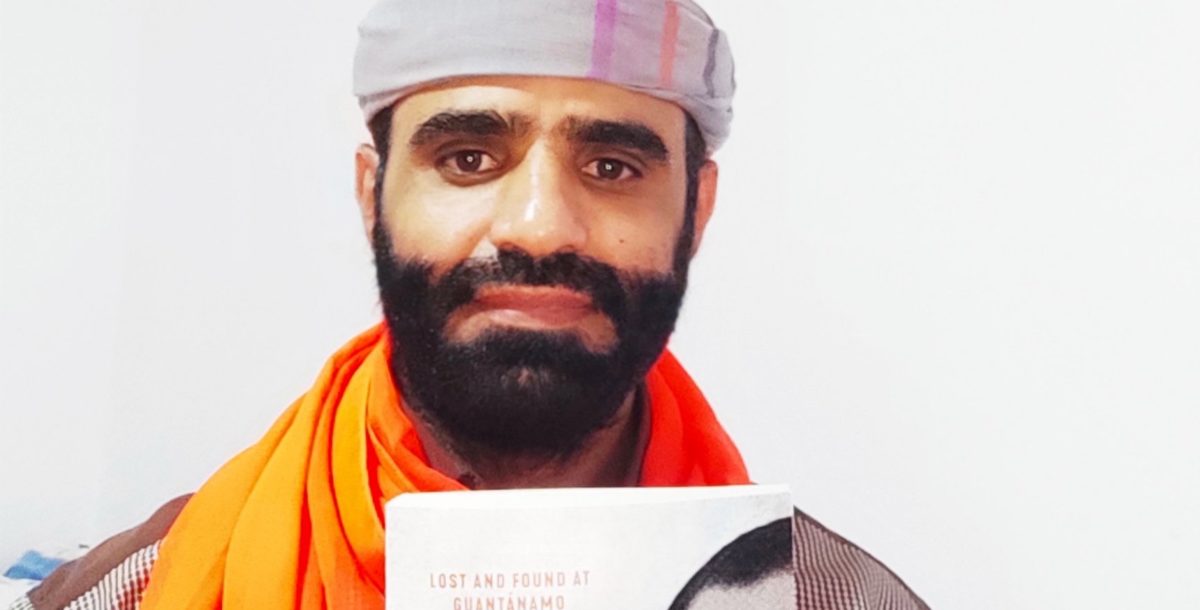

Adayfi’s eloquent memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo, is a deeply personal testament to the horror of the prison. It’s also a searing indictment of the brutality of the U.S. military and of those in charge there, including General Geoffrey Miller, a relentless torture advocate who would go on to “Gitmoize” Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, and the string of Presidents/Commanders in Chief, from George W. Bush to Obama to Trump and now to Biden.

“Please allow me to take you on a journey through Guantánamo,” Adayfi writes in the book’s introduction. “Buckle up and prepare yourself. I will be your guide, but don’t worry — you won’t have to wear the orange jumpsuit, shackles, or hood. You will be free every night to leave behind the fences and isolation cells and rejoin your life. But I think you will come back and join me again to see a side of Guantánamo few people have experienced, where yes, there is much pain, but there are also unexpected moments of beauty and joy that will take your breath away. This is my Guantánamo.”

Born into a large family in rural Yemen, Mansoor did well in school and was sent to Afghanistan to help with a research project when he was just 18. He recounted what happened there:

“One day, after 9/11, I was kidnapped by the warlords…American airplanes were throwing a lot of flyers [pamphlets] offering a large bounty of money. I was sold to the CIA as an al-Qaeda general, middle-age Egyptian, a 9/11 insider. I was taken to the black site, where I was tortured for over two months.”

He’ll never forget what happened there:

“No one knows how many people actually died there. There was no limitation to what they could do to you — hang on the ceiling all the time, upside down, even blindfolded, naked…Standing, and there’s no rest. Twenty-four hours, sleep deprivation, beating, waterboarding.”

Shackled and hooded, he was flown 40 hours from Afghanistan to Guantánamo. His captors hung a “Beat Me” sign around his neck, and the guards on board obliged, beating him throughout the journey. At Guantánamo, the abuse continued. Eventually, the prisoners organized themselves and began a hunger strike.

“Our bodies were the battlefield, because Americans torture us, abuse us and beat us on our bodies; also, we were torturing our bodies by hunger strike, by trying to resist. It was a slow journey toward death.”

While he suffered countless beatings and horrendous interrogations at the hands of the guards, he still felt compassion for those who returned from a combat tour in Iraq or Afghanistan: “I saw how the guards came back, many of them were mentally devastated. When you see a broken soul, it’s the most severe pain.” Another guard moved him deeply when she refused a direct order to drag him to an interrogation.

“Hope, it was a matter of life or death. You have to keep hoping,” Adayfi reflected. “That place was designed just to take your hope away.”

He defiantly wears an orange scarf, rejecting the warnings given him by a Guantánamo prison psychologist and an International Committee of the Red Cross representative, who said the color orange might trigger post-traumatic stress.

“What I have learned at Guantánamo, I will never keep silent,” Mansoor Adayfi, Detainee #441, concluded on Democracy Now!, “keeping silent only gives the oppressor a means to oppress you more. So, I will never keep silent.”

Amy Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 1,300 stations. She is the co-author, with Denis Moynihan, of The Silenced Majority, a New York Times bestseller. This column originally appeared on Democracy Now!