The original French text is available here.

We are a collective from the fields of law, philosophy and journalism that citizens of all orientations and origins have sought to join. Among us are separatists, federalists and “agnostics” with regards to the constitutional future of Quebec.

It is with great concern that we commit these words to denounce the Quebec Charter of Values (formerly the Charter of Secularism) project, announced by the Parti Québécois government. The main focal points of this project were announced during the last election campaign and reiterated by carefully orchestrated leaks to the media, before being officially announced by Minister Bernard Drainville. The Charter would seek to define “clear” guidelines governing requests for religious accommodation, to guarantee the neutrality of the state by banning employees from wearing “conspicuous” religious symbols, and to do no less than to restore “social peace.”

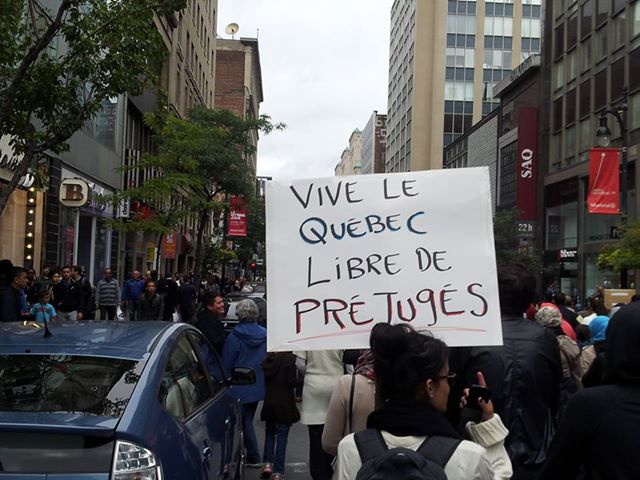

From the outset, the fact that the government calls on the few requests for accommodation as being responsible for a social crisis speaks volumes about the work done by some of the province’s most prominent media columnists. Explosive and populist headlines, sweeping and judgemental commentaries and superficial analyses have marked Quebec’s media landscape since the emergence of the public debate on religious accommodation. Using manifold shortcuts, tabloids and news channels continuously portrayed a besieged Montreal, inundated by unreasonable requests for accommodations from intransigent immigrants. Over the years, they were able to anchor a real fear for the survival of the Québécois identity in many of our fellow citizens. We regrettably note that today, our government seeks to exploit this fear for votes.

We strongly condemn that a handful of anecdotal events that sparked the imagination serve as a justification for our government to remove fundamental rights of some of our most vulnerable citizens. The publication of this manifesto seeks to explain to our fellow citizens and our decision-makers the basis of our opposition.

I. Inconsistency

It is probably no coincidence that the government has decided to rename its Charter of Secularism under the title of the Quebec Charter of Values . Indeed, the use of the term “secularism” to describe such a project must have seemed incongruous even to government bigwigs. Recall that wearing conspicuous religious symbols is to be banned for officials in order to ensure the appearance of the state’s neutrality and impartiality. However, the crucifix installed above the Speaker’s chair at the National Assembly, in the same enclosure where laws are passed, shall remain.

Mr. Drainville explained that the crucifix was a historical symbol, representing our heritage, rather than religious one. However, all religious symbols are rooted in history; it is for this reason that believers attribute as much importance to them. In short, the impression that emerges from this measure is that of a two-tiered secularism in which the religious symbols of the majority are celebrated, even within the highest echelons of our parliamentary democracy, while minority religious symbols should be banned as a threat to our values. Minority in symbols are thus stigmatized.

From the outset, this Charter of Values raises several intractable issues by their very nature. First, what is a conspicuous sign? Is the kirpan, an invisible religious symbol since it is concealed under clothing, to be considered a conspicuous sign? What about a crucifix worn under clothing? Is it permissible to wear a sweater with a printed cross? Will all scarves used to hide hair be considered religious? How long must a beard be in order to be considered a religious symbol? And who will establish the religious character of a piece of fabric?

Moreover, it is wrong that Minister Drainville claim that there are no clear guidelines regarding religious accommodation, leading to a moral obligation for the state to legislate and clarify the process. In reality, for an accommodation to be granted, there must be 1) a sincere religious belief, 2) a real violation of the right of freedom of religion, and 3) a proposed accommodation does not impose an undue restriction of the rights of others. If there is a need for religious accommodation, we propose that there is rather a desperate need for education. As such, the Human and Youth Rights Commission could publish an explanatory guide with an educational scope, to benefit concerned managers. One thing is certain: the addition of certain conditions to increase the burden of those requesting accommodation will do nothing to simplify or clarify the debate. Instead, the addition of these conditions will necessarily transfer the stage of constitutional oversight to the courts, which will unnecessarily monopolize time and money, in order to add “clear guidelines” to those that are already exist and work.

We also wish to denounce the misleading association made by some commentators between Canadian multiculturalism and respect for religious minorities. Far from being a Canadian invention, freedom of religion was protected by different apparatuses in most democratic countries over the course of the second half of the twentieth century. As such, Quebec legislated on the topic before the federal government had, by adopting its own Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1975, seven years before the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In addition, the Quebec Charter of Rights goes further than its federal counterpart by also governing matters of private rights. This means that Quebec has historically chosen to give additional protection to vulnerable groups, including religious minorities. And Pierre Elliott Trudeau has nothing to do with it.

II. Exclusionary effect

We hope that the government’s objective is not to exclude thousands of our fellow citizens from employment within the public sector. Yet under the guise of promoting the neutrality of the state, the expected effect of the prohibition to wear any obvious religious symbol in fact would be to exclude citizens unable to choose between the requirements of their conscience and those of their job. It is precisely to avoid this kind of dilemma that Charters of Rights have protected freedom of conscience and religion for over thirty years.

The unemployment rate dramatically affecting Quebec immigrants is among the urgent problems in terms of integration. However, the ban on religious symbols in the public service, schools and daycares can only exacerbate the exclusion of immigrants from the Quebec labour market. In this regard, the ban will only contribute to making women wearing the hijab more vulnerable and increase inequality between men and women, particularly in terms of access to employment. It is therefore to be expected that this Charter, proffered as a tool to help achieve gender equality, would have the opposite effect.

Moreover, the demagoguery and populism espoused by some columnists, then conveniently repeated by some politicians, would only strengthen this exclusion. Thus, when Minister Drainville indicates that this will be the end of the “free pass,” when the government endorses the statements made by the President of the Quebec Soccer Federation stating that Sikhs wishing to wear their turban would simply have to “play in their own backyard,” it reinforces existing prejudices against religious minorities, as well as the impression among some quebecers that by accepting to accommodate a group of individuals in favour of integration, we grant them a privilege.

Worse yet, in interview on 24 heures en 60 minutes on RDI, August 23 2013, Minister Drainville gave the example of the windows of the YMCA being frosted at the request of Hasidic Jews to justify the urgency of the intervention. However, this anecdotal event has nothing to do with the concept of reasonable accommodation, as developed and applied under our Charter of Rights. The same goes for the famous anecdote of the sugar shack interrupted by a Muslim prayer, or of the Christmas trees removed from public places. Recent statements by the Minister therefore are exceedingly worrisome, as they seem to confirm that the measures put forward by the government are based on stereotypical anecdotes rather than factual analysis.

With this draft Charter of Quebec Values, the Parti Québécois fulfills its deviation of a civic nationalism towards an exclusionary nationalism, a rejection of others and a withdrawal within. Ironically, by requiring that some Quebecers choose between their Quebec identity and the respect for human rights, the Parti Québécois is running a much greater risk of weakening identity than of strengthening it.

III. Fear of the other

The Quebec Charter of Values offers an exclusive concept of secularism under the banner of a common identity. Although the question of identity in Quebec certainly calls for our attention in all deserving seriousness, it also requires that the lines of communication and dialogue remain open to all quebecers. The question of identity must also raise the correlative question of citizenship if it is equally true that democratic debate must consider the moral and legal equality of all citizens who comprise the examples.

What are the criteria for membership in a political community: ethnic affiliation, linguistic affiliation, cultural affiliation, religious affiliation, civic affiliation? If we resist the temptation to demonize the defenders of this conception of secularism by charging them with racist and xenophobic intentions (because it only leads to polarizing the positions of both sides and truncating the opportunity for a real exchange), it remains that the consequences of the Charter can be seen as a form of political xenophobia. One can understand the original intention behind this secularism project: to make public space void of any particular bias. Nevertheless, it is a misunderstanding and a poor targeting of the fundamental issues of a political design of secularism, not a metaphysical one.

Debates about religious beliefs are insoluble and it is also desirable that a democratic society characterized by the free exercise of reason lead to legal and political protection of the freedom of conscience and religious diversity. We can only aspire to a political secularism that manifests not physically, but in the spirit of secularism which should guide the exercise of our functions in the public sphere. Making cultural and religious affiliations invisible is a naive and illusory attempt to deny the inescapable fact of pluralism within our open societies. An understanding that is even more naive seeing that some of us carry our cultural, ethnic and religious differences in our facial features and skin colour (many Asians are Buddhists, for example). The real test for secularism is the acceptance both of the visibility of differences and of the need for consensus on the spirit of tolerance and impartiality which should govern our interactions respectful of these differences.

With regards to the argument of male/female equality, extremely important debates should definitely take place in the public sphere in order to promote and protect women’s rights in Quebec society. However, the linkage between the concepts of secularism and equality leads to problematic interpretations. Banning the wearing of religious symbols and, namely, let’s face it, the veil by women in the public sphere violates a set of fundamental democratic principles linked to individual rights, the freedom of conscience and religion and minority rights. The Quebec Charter of Values would result in an undue burden … upon women. From this point of view, some might consider this notion of secularism as being, in essence, much more sexist, occidentalist and paternalistic than at first glance.

Several feminist voices, including those who have rallied to the positions held by the Women’s Federation of Quebec in the context of the Bouchard-Taylor Commission, attest to the fact that the struggle for women’s rights must not be at the expense of freedom of belief. Not only must we respect the autonomy of women in terms of their religious beliefs and their moral and ethical rectitude with regards to the execution of their various professions and public functions, but if there doubts remain in the minds of some as to the kinds of pernicious discrimination that might cause them harm, coercive measures preventing the display of their religious beliefs are not necessarily more important or more effective than addressing the social determinants that can lead to constraints limiting their freedom. In other words, it could be that working towards ensuring equal opportunity, equal access to education, equal socio-economic standards of living, the equality of means of expression, the equality of the options made available to all in a democratic society, constitute the basic measures that a just society should rather promote through public policies in the name of gender equality.

IV. Slippery slope

Added to the above is the following: any attempt to prioritize certain civil liberties is the perfect recipe for a predictable failure. Fundamental rights are, by definition, fundamental. They must, by force of circumstance, reign atop the hierarchy of constitutional order. Consequently, any modulation or prioritization scheme affecting these rights requires both societal consensus and a motive as equally transcendent as pre-determined. It is clear that none of these conditions are met in this case.

Take, as an illustration, Minister Drainville’s latest fad: the imperative of male/female equality, which would be, a Quebec value in need of protection, according to the minister. Is the minister aware that Article 28 of the Canadian Charter and Article 50.1 of the Quebec Charter, already protect this very same gender equality? Would he also not be aware of the predominant character of this provision on any application of multiculturalism, be it theoretical or practical? Would it then be possible for Drainville Minister to explain how the banning of any religious symbol in the public sector ensures this desired equality?

Let’s admit this instead: the current scheme is quite unsubtly a red herring. A mere pretext to impose certain values, a certain conception of religious practice, necessarily those of an artificial majority at the expense of various rights, fundamental ones, of minorities. And this is precisely where the problem lies.

In fact, the very essence of any bill of rights is to ensure the rights of vulnerable minorities against the dictates of the majority. It is what the community of nations hoped for in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As well as what all Western legislatures desired by inscribing these principles in their constitution or quasi-constitutional laws, having incited a necessary consensus amongst the international community.

Consequently, let us remember that any changes to these can not be taken lightly. The trivialization of the violation of certain individual rights, especially on the grounds of electioneering, has itself visibly the same intrinsic gene of future slippages. In fact, it is easy to identify this kind of populist scheme. What is more complex, however, is successfully predicting the extent of the damage it will cause.

Conclusion

With the announcement of the Quebec Charter of Values and the reactions to it, we recognize that there is some discomfort within the Quebec population, which is calling for “clear guidelines” and wants to see its culture and identity reinforced. However, we believe that these requirements do not have to be capped with an oppressive legislative apparatus whose impact on the civil liberties of minorities and, by the same token, everyone, could be devastating.

Regarding guidelines, they already exist. They must simply be publicized and popularized to administrators and citizens so that they feel sufficiently equipped to accommodate the needs of minorities without the majority being bullied. In terms of culture and identity, Quebec will continue to celebrate its authenticity through a rich culture protected by an integration model that has proven its worth. The concern felt about the survival and development of Quebec’s identity only confirms the merits of investing in culture and stresses the importance of teaching history in schools so that future generations feel a strong identity that has evolved with the winds and tempests. We believe that the Charter of the French Language and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms are necessary and sufficient tools to protect Quebec values.

Furthermore, never in history has exclusion, such as we feel this draft charter has imposed upon a minority to choose between his or her conscience and his or her survival, been a part of Quebec values. Quebec has always been a warm and welcoming land where everyone could contribute to the greater social quilt. We believe that it is through greater social diversity and not ostracization by a few individuals that we can continue to live in harmony. Quebec’s identity is not attained by the rejection of the Other.

We therefore urge the government to review its position on the draft Charter of Quebec Values, a charter that could have irreversible consequences for the rights of minorities and, thereby, for justice and social peace. We also invite our fellow citizens to be more demanding of the government, so it might not merely participate in the utter fabrication of a crisis of which it purports to be the saviour instead of addressing the issues that truly threaten the social fabric, such as the economy, employment, culture, justice and education.

It is tempting to accept a simple solution to a complex problem. We invite our fellow citizens to not be cajoled by populist proposals that respond to unfounded fears, but rather to learn about the potential consequences of such provisions. Above all, we ask the government to abandon any project that would result in further making a segment of the population more vulnerable and eroding the scope of fundamental rights on which social peace, which is so dear to Quebecers, is based.

Jain Bourget – Lawyer and blogger FaitsEtCauses.com; he has been the spokesperson for lawyers opposed to Law 12 in the Spring of 2012;

Frederic Berard – Constitutional lawyer political scientist;

Ryoa Chung – Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Université de Montréal;

Judith Lussier – Columnist

Translated from the original French by Translating the printemps érable, a volunteer collective attempting to balance the English media’s extremely poor coverage of the student conflict in Québec by translating media that has been published in French into English. These are amateur translations; we have done our best to translate these pieces fairly and coherently, but the final texts may still leave something to be desired. If you find any important errors in any of these texts, we would be very grateful if you would share them with us at [email protected]. Please read and distribute these texts in the spirit in which they were intended; that of solidarity and the sharing of information.