On Sunday, August 10, people both inside and outside the prison system came together in solidarity against prisons and the global rise of hyper-incarceration. In 1975 Prison Justice Day began as a day of silence and mourning amongst Canadian prisoners in response to the death of Eddie Nalon which was caused by the negligence of prison guards while Nalon was in solitary confinement. Since then the occasion has spread across the world, fueled by an increasingly widespread understanding of the immense social costs of prisons.

Change cannot happen soon enough. While the politics of criminal justice may be beginning to shift, Canada’s federal government is pursuing an aggressive tough-on-crime agenda. Federal legislation has increased sentence lengths, imposed unrealistic and probably unconstitutional fines on offenders, and deprived many currently incarcerated people of many basic amenities during their time in prison.

Provincial and federal governments build prisons and increase spending on criminal justice and corrections while funding for housing, treatment, and mental health care is cut. According to the Adult Correctional Services Survey of Statistics Canada, between 2002 and 2012 criminal justice spending nationally rose by 23 per cent, with Provincial/territorial expenditures currently around $1.93 billion in 2010-11. According to the Office of the Correctional Investigator, the per capita cost in 2010- 11, adjusted for inflation, was $51.80, increasing from $42.80 per capita (21.0 per cent) in 206-07.

In B.C, Premier Christy Clark has overseen a $128 million prison building campaign, the largest investment in corrections in the province’s history. Meanwhile funding for legal aid has not increased since 2002, amounting to a 40 per cent proportional decrease in funding for legal representation for low-income people. In Vancouver, policing is the largest and fastest growing endeavour on the municipal budget. In a time of austerity, corrections and criminal justice are glaring exceptions.

Despite this spending, life within Canada’s prison walls, by most measures, has deteriorated significantly over the past five years. Prisons in Canada are chronically over crowded, with prisoners frequently double-bunked (more than 20 per cent federally), a practice that contributes to violence, and may violate international human rights laws, particularly the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. The rates of violence and self harm within federal correctional institutions, as reported by the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI), have increased massively. According to OCI’s numbers, over the past five years, use of force incidents in Federal Corrections have increased by 91 per cent, incidents of self-injury have increased by 236 per cent, and assaults by 124 per cent.

Prisons remain harmful from a public health perspective, negatively impacting the physical and mental health of those detained. Among prisoners, HIV infection is seven times more prevalent, while the rate of Hepatitis C is 40 times greater. Recent research by the B.C Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDs found that a stay in prison is correlated to an overall lower quality of treatment upon release, whether that treatment is occurring within prisons or outside of them. 21 per cent of HIV infections among injection drug users in Vancouver may have been acquired within prison. Mental illness is also commonplace. The OCI warns that “Canadian penitentiaries are becoming the largest psychiatric facilities in the country” yet nearly one-third of the Correctional Service of Canada’s total psychologist staff complement is either vacant or “under-filled.”

B.C is no exception to these disturbing national trends. A 2009 report showed a need for double the psychiatric care beds that were available in the province. An estimated 50-70 per cent of prisoners in B.C. have hepatitis C, ten per cent of women prisoners in B.C. have HIV, and prison staff estimate that 80 per cent of prisoners have a substance abuse disorder. Studies have shown that 26 per cent of B.C. prisoners have a mental disorder unrelated to substance use.

While life within prison walls seems to be getting worse, for many people released from prison life in the community is a struggle. The stigma of a criminal record, combined with an acute lack of affordable housing, and an underfunded social safety net catch many in a cruel nexus between prisons and marginalized communities. Since 2004 more prisoners are held in remand centers (temporary detention awaiting trial) than are in sentenced custody. Remand prisoners have less access to programming and release planning than those held in sentenced custody.

Rather than getting serious about poverty and social inclusion, tough on crime policies pour money into largely symbolic anti-drug initiatives that accomplish little of substance. Consider illicit drug use in prisons, which has long been a priority of conservative tough-on-crime posturing.

In 2008, in response to concerns about drug use among prisoners, the Federal Government launched a five year $120 million drug interdiction strategy in federal penitentiaries. This anti-drug offensive involved tightening security within correctional facilities, more stringent search standards, purchase of expensive “detection and interception technologies” like x-ray machines and thermal imaging goggles, and the expansion of drug sniffing dogs in all federal prisons. During the same period drug treatment programming administered by The Correctional Service of Canada was cut by $2 million.

According to a 2012 report by the Office of the Correctional Investigator, “the rate of positive random urinalysis,” the best available objective measures of drug use in prisons, “has remained relatively unchanged over the past decade despite increased interdiction efforts.” In other words, Corrections Canada has been unable to staunch the flow of drugs into prisons, despite their best efforts.

While these interventions failed to reduce drug use within federal penitentiaries they did succeed in reducing the quality of life for prisoners. Criminal justice institutions are not able to stamp out illicit drug use, even within correctional institutions. Interventions that have been shown to work, like housing first approaches, prescription heroin, supervised injection sites, and on demand detox, are unavailable, underutilized, and/or underfunded.

Prisons do succeed at one thing: hiding human suffering from view. The ongoing violence of colonialism, violence against women and migrants, assaults on working class people and the labour movement, and growing social inequality are made acutely visible to anyone visiting a prison. Here again, the OCI provides telling numbers: the average education of a federally incarcerated person does not surpass that of middle school, the majority of offenders are chronically underemployed before they enter the prison system, 70 per cent of federally sentenced women report histories of sexual abuse, and the Indigenous offender population has increased by 47.4 per cent over the past decade, which now represents 22.8 per cent of the total incarcerated population while the Caucasian offender population decreased by four per cent over the same period.

Prison Justice Day is a moment in which we are called to task by the bravery of those organizing behind bars to acknowledge and work against these trends. By bringing light to the violence and abuses that happen within prison walls we can help put an end to them.

This article was originally published at The Mainlander. It is republished here with permission.

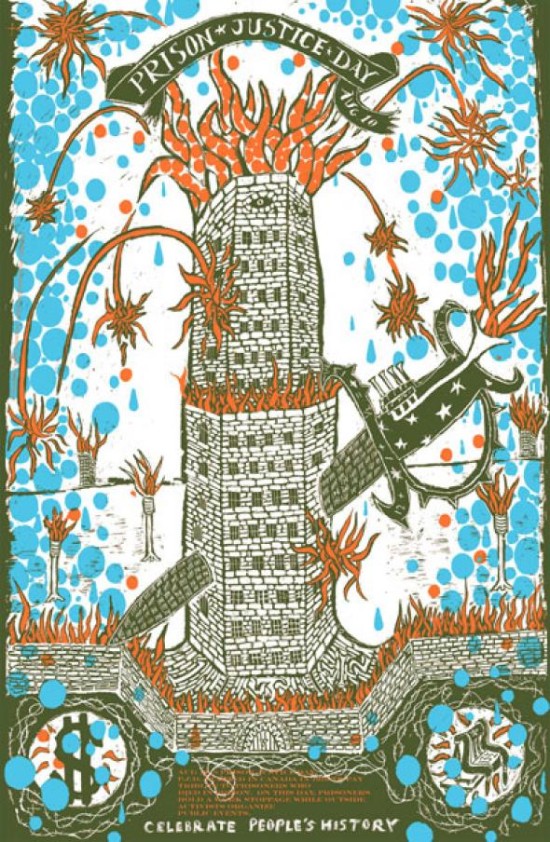

Artwork by Rocky Tobey. Found at Justseeds.