Is something rotten with privacy?

The word “czar” in politics, a colloquial designation of an omnipotent commissioner responsible for the state of affairs in a particular area, highlights the high degree of his or her autonomy and the scarcity of checks and balances under which the czar acts. The privacy commissioner of Canada is one such czar with the mandate to protect citizens’ privacy rights.

The independence of the czar from other government bodies has a clear rationale: that person is expected to curb the government’s appetite for invading the citizens’ privacy. But should that czar also enjoy a significant degree of autonomy from citizens?

The privacy commissioner deserves credit for many good things. In the recently released Annual Report to Parliament she discusses outcomes of audits of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority and selected databases under the custody and control of the RCMP.

Many breaches in the privacy legislation have been identified in the operations of these government bodies. Air travellers would hardly disagree: practices of screening at the airports have long been subject to criticism because of potential breaches of passengers’ privacy and the lack of respect for their human dignity. These endeavours on the part of Canada’s privacy czar justly received accolades from both the press and general public.

A reasonable question nevertheless arises:

Should citizens rely on the czar’s insight and expertise in the matters of protecting their privacy rights or they should take their own initiative and guide the commissioner’s efforts in this highly sensitive area by helping her spot problems that call for solutions? Does the commissioner always have the last word when identifying and addressing citizens’ privacy concerns?

When introducing the Privacy Act (PA) in July 1983, its architects wanted to have an ombudsperson responsible for helping citizens ensure that their privacy concerns would be addressed. The ombudsman’s office was expected to operate in a “bottom-up” manner, by focusing on issues raised by Canadians through their inquiries and complaints. “The Commissioner will investigate on behalf of complainants, taking up their cases and making representations on their behalf.”

In Jan. 2001, the commissioner’s scope of responsibility was extended with the enactment of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, PIPEDA. While the PA deals with privacy issues in interactions between Canadians and government bodies, PIPEDA was intended to protect citizens’ privacy in their dealings with private businesses.

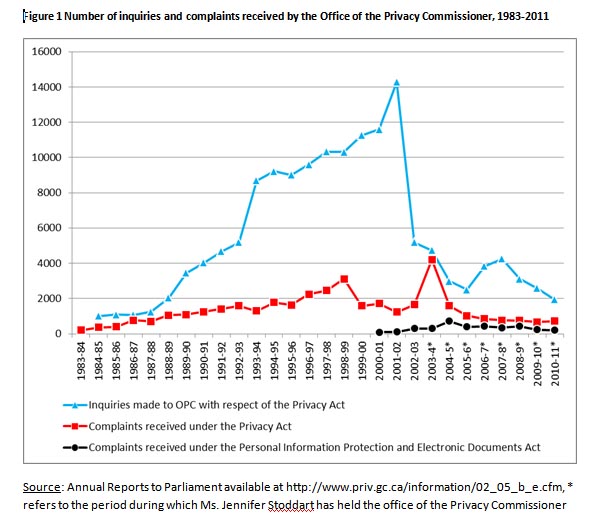

In the first 20 years since the establishment of the position of ombudsman position, the office dealt with a steadily growing number of both inquiries and formal complaints, which arguably reflects the increasing complexity of government, increased awareness of Canadians about their privacy rights and also a growing population.

This trend was reversed radically between 2003 and 2005 however: Canadians started to make fewer and fewer inquiries and to file fewer and fewer complaints under both PA and PIPEDA. For instance, during the period from April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011, Canadians lodged fewer complaints under PA than in 1986-7. The number of complaints under PIPEDA dropped below the 2002-3 level. The ombudsperson has acknowledged this slippage but has not offered an explanation.

The number of inquiries and complaints received by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, 1983-2011 (Source: Annual Reports to Parliament and see above) refers to the period during which Jennifer Stoddart has held the office of the privacy commissioner. Can this drop in the number of citizen contacts with the ombudsperson be attributed to the increased efficiency of government bodies in meeting and anticipating the privacy concerns of their constituency or to Canadians growing reliance on the ombudsperson’s website as a source of information about privacy? A simple comparison with the situation in another country with a similar culture, a similar level of development and a similar legal system could be of help in this respect.

The United Kingdom seems to be a good point of comparison, taking into consideration the intense cultural ties between the two countries and the fact that their legal systems are based on common law. The British information commissioner has an informative website as well. The only substantial difference consists in his or her broader mandate: it also includes freedom of information inquiries and complaints, whereas in Canada a separate office, that of the information commissioner, deals with such matters.

A completely different pattern characterizes the dynamics of inquiries and complaints in the case of the U.K. Their number has been growing over the past seven years. In 2010-11, the UK informational commissioner received in total 114,000 inquiries and 26,227 data protection complaints (4,458 of them refer to government bodies).

The difference between 4,458 complaints in the UK and 708 in Canada cannot arguably be attributed to the superior efficiency of the Canadian government or to a different total population. Canadians lodge 2.7 complaints under PA per 100,000 of total population as compared with 7.2 complaints filed by the Brits, i.e. almost three times fewer.

A clue that might account for this difference could perhaps be found by looking into how the two ombudspersons deal with complaints. In 2010-11, 22.8 per cent of cases considered by the Canadian Commissioner were resolved, whereas the number of resolved cases was double in the case of the U.K. Commissioner (44 per cent).

To conclude, the British privacy watchdog acts less as a ‘czar’ than as an adviser, investigator and public counsel giving high priority to concerns expressed by citizens. As for the Canadian counterpart, her office seems to prefer taking initiatives on its own and proceeding in a “top-down” manner when spotting urgent privacy issues. Does the latter approach accurately reflect the intentions of the Canadian legislators and their constituency? This question is at least worth discussing further.

Anton Oleinik is an associate professor of Sociology at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Dear rabble.ca reader… Can you support rabble.ca by matching your mainstream media costs? Will you donate a month’s charges for newspaper subscription, cable, satellite, mobile or Internet costs to our independent media site?