As we are bussed through Caracas to the airport, vultures perched on lamp posts on the concrete banks of the Rio Guaire remind me of a T-shirt I had in high school. The T-shirt featured two vultures in a tree. One addresses the other: “Patience my ass, I’m gonna kill something.”

The vultures hanging around what’s essentially a concrete drainage ditch through the capital might represent moneyed interests both inside and outside Venezuela. The country is a treasure trove of petroleum and minerals, and while the socialist government has made many mistakes, it doesn’t seem poised to fail anytime soon. And some vultures just can’t wait. Sanctions and an infowar by corporate media, parroting the neoliberal party line, have turned Venezuela into an economic warzone.

Since Hugo Chavez was elected in 1998, capital has attacked the country in every possible way. There was a coup d’etat, a general strike of petroleum workers, a “general strike” that sabotaged petroleum wells and refineries, and street violence by right-wing paramilitary gangs. None of it really shook popular support for the socialist government in election after election. On the ground, the reasons are obvious. Most of Venezuelans are poor or working class. The Chavista socialist party, the PSUV, has built over 2 million new housing units, instituted free education and health care, educated the army, provided every child with a laptop, and runs numerous food programs for the poor. One can argue about the efficacy of these programs, but they are the only things any government has ever provided for the majority of Venezuelans. Regardless of the quality of the housing, eight million people out of a population of 32 million currently live in government housing with a school, community center, and health centre in walking distance.

Because the middle and upper classes in the country form a small minority, the right-wing parties can’t win an election. The next best thing is to deligitimize elections altogether. The recent election in Venezuela was a prime example. The leading candidate, Henri Falcon, declared the election a fraud before the results were even tabulated. The U.S. imposed new sanctions the next day. The G7 followed two days later with a statement “rejecting” the elections “for failing to meet accepted international standards”.

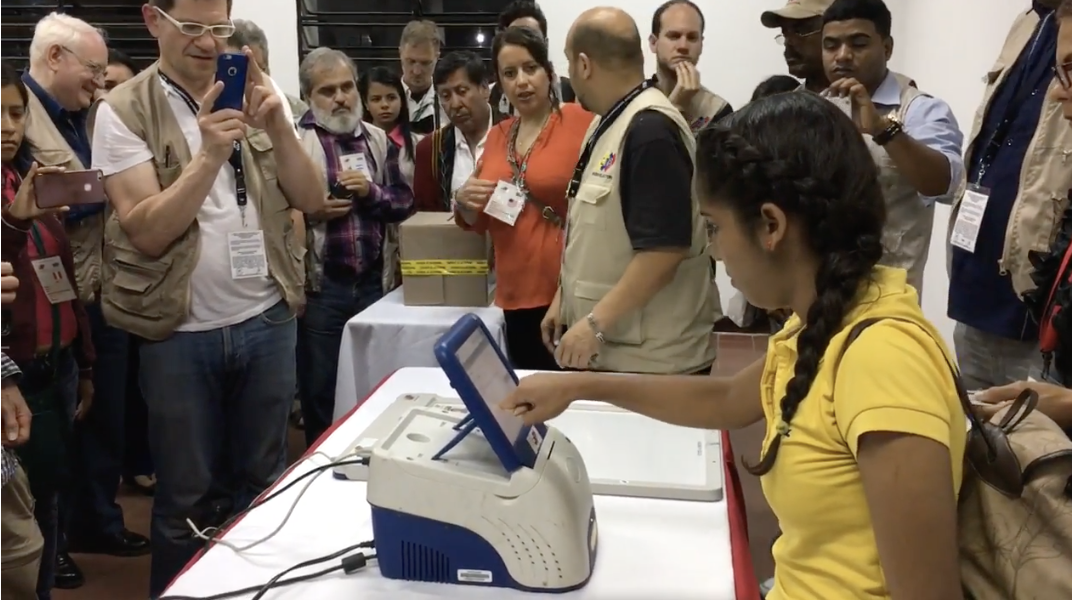

Venezeuelan elections, like Caesar’s wife, must be above suspicion, so the Venezuelans have developed a polling method that creates numerous checks to ensure that the result is verifiable. A voter must go to their poll, unlock the voting machine with the fingerprint biometric on their national identity card, and vote electronically. The machine issues a receipt/paper ballot verifying their vote and which they then deposit into a ballot box. After voting the citizen must sign off and provide a fingerprint beside their signature certifying they have voted. At the end of the day the results are transmitted electronically to the Election commission, and 54 per cent of ballot boxes are counted to ensure the machines tabulated the votes correctly. No hanging chads or butterfly ballots here. Just a high turnout of working-class and poor electors who know that keeping their welfare state depends on keeping the socialists in power. But because the neoliberals can’t win, those checks and balances are “failing to meet international standards”.

Because a lot of corporate oil ended up under the Venezuelan jungle or seabed, something else needs to be done when the electorate continuously votes irresponsibly. Like in Guatemala, Iran, Chile, Honduras, or Brazil, etc. before, enter the inpatient vultures in the form of economic hit men wielding disinformation, hyper inflation, sanctions, blockades and violence to do the job of opening the market, which democracy failed to do.

When I went to Venezuela I had to ask myself, am I being a useful idiot for an authoritarian regime? Am I just being taken on a propaganda tour to legitimize sham elections? That is not something I wanted to do. But after five days spent touring public housing, walking through the City, and sitting in luxury hotel lounges stone cold sober (the country goes dry for three days before and one day after the election), I concluded that the only thing “wrong” with this country is the poor were winning the class war at the ballot box. The rich just didn’t have the numbers to outvote them and couldn’t fool them with

pie-in-the-sky when the socialists had already provided a home and a school. It is said that people vote their values and not their interests, but the average Venezuelan knows better than to do that. The useful idiots are corporate media outlets parroting disinformation, in order to destroy a country to benefit their corporate masters.

In Caracas at least, there doesn’t seem to be anybody starving, the narrative of the western corporate media to the contrary. There don’t seem to be many homeless either. Walking through the city, I was accosted by fewer panhandlers than in Toronto. The shops have a limited amount of product, but basic foodstuffs like fruits, vegetables, and fish are available. Ice cream is sold by peddlers on the street. People are getting by. The government even has food trucks selling nearly free arepas around the city. Those had a fairly long line up. Funny though, despite a short money supply to buy foreign goods, nearly every shop has as much Coca Cola as anyone could possibly want.

But as soon as you enter the departure area of the airport. You suddenly remember what it’s really all about. There is a massive Duty Free shop that rivals anything Miami offering the array of designer luxury brands that people buy when they travel. There are trendy bars, restaurants and cafes. The burgers are massive and juicy, dripping with cheddar and bacon. You can get ceviche in a martini glass. It seems like at the airport, on the far side of security, we cross back through the looking glass into the global consumer wonderland. Anyone is free to cross over, there is no limitations on freedom of speech, assembly, or travel. But in this respect, Venezuela is like Flint, Michigan, or Appalachia, or any number of North American indigenous communities. You can leave any time, if you can afford the ticket.

My father left Portugal for Venezuela, a fabled land of opportunity, on a ship in 1955. Things were working out for better for one of my uncles in Canada, so two years later my father left Venezuela on a Pan Am flight to join them. He had a long and happy life in Canada. My mother joined him two years later, and I was born in Canada, though I might just as easily have been born Venezuelan. I was lucky. Canada is a generally a peaceable and prosperous place where the predations of empire don’t affect me too keenly as a white man. I grew up in a time of upward class mobility aided by decent public education, public healthcare, and available full time jobs with health benefits straight out of school. There were also periods like this in 20thcentury Argentina, Chile, Venezuela and Brazil, but those times ended as those countries became the early laboratories of neoliberal capitalism.

When I was nine, I borrowed a book about hawks from a public library and developed an amateur ornithologist’s interest in birds of prey. My eyes always scan Canadian skies for Red Tailed Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Peregrine Falcons, Sparrow Hawks, and even the occasional Osprey. But what I have noted in the last few years is that carrion eaters are venturing further north. These vultures are easily distinguished by their long black wingspan used to cruise lazily on thermals looking for dead stuff, and their heads that are featherless, so they aren’t be fouled when they go neck deep into bloated carrion to beak out the juicy bits.

Apparently, the pickings are getting slimmer elsewhere because of the decline of migrating herd animals. So global warming and plentiful roadkill along the highway systems has let them north. So although growing up in Canada I never saw vultures, I see them all the time now, circling over my land.

Photo: Humberto Da Silva

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.