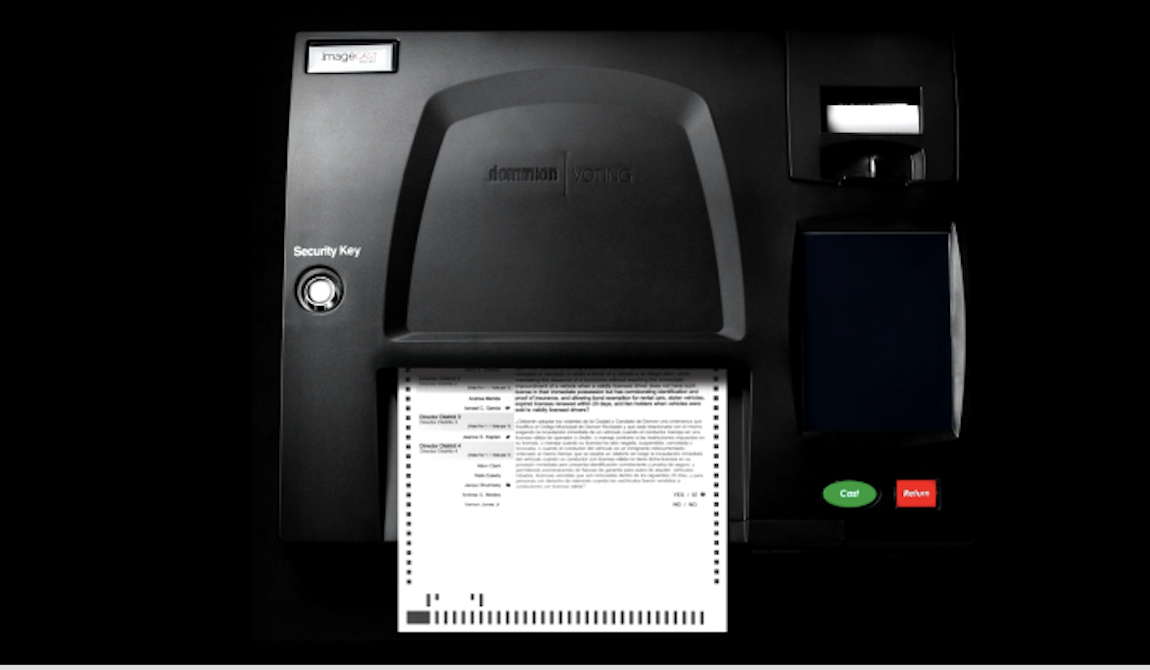

A seismic shift will occur in Ontario politics on June 7 regardless of which party wins the election: electronic vote-counting machines will be used across the province for the first time.

Machines will scan voters’ paper ballots and calculate the totals at each polling station that is equipped with them. Ninety per cent of the ballots will be counted this way. The rest will be counted by hand, as not all polling stations will have machines. When the polls close, offsite computers will add up the votes.

On June 1, CBC News reported that the Progressive Conservatives, “wrote to Elections Ontario this week to flag several issues, including concerns about protection from hacking and the certification of the vote-counting machines.” Elections Ontario’s chief administrative officer, Deborah Danis, was quoted as responding, “There is no possibility that the counts could not be fully corroborated. I would actually argue that the introduction of technology increases our accuracy.”

Unfortunately, this response from Elections Ontario falls far short. Here’s why.

The major problem with the plan is that scrutineers, appointed by parties to watch for cheating, will no longer be able to observe the count for 90 per cent of the ballots. Nor will they be permitted to object to any aspect of this automated count.

Unfortunately, the government offered no public consultation about this switch before making it law in 2016 — even though it is just as consequential as past proposals that warranted a referendum.

Elections Ontario is framing this as a change for the better by speeding up ballot counting and reducing the number of polling station staff, which they say are hard to find. In a test of electronic voting in a 2016 by-election, the agency found e-counting ballots took only half an hour, compared with 90 minutes, for hand-counting.

The convenience and cost savings have led Ontario municipalities to use tabulators in their elections for years, but it is far from clear whether their counts were ever accurate.

One source of doubt is how the devices are tested by the cities. On the City of Toronto’s elections website, for example, there is only one document about tabulator testing. It says they run sample ballots through the tabulators and if the counts are correct they assume the machines will function correctly on election day.

Unfortunately, as Volkswagen car owners found out, this is not a good way to test computerized devices.The company illegally programmed their emissions-control devices to behave correctly on test day, but spew 40 times more nitrous emissions in real-world driving.This proved to be a $15-billion boondoggle for Volkswagen: the largest settlement of an automobile-related consumer class-action lawsuit in American history.

Another good reason to distrust these devices is a June 2017 report from Canada’s Communications Security Establishment, warning that cyber threats to elections are growing worldwide. The report concluded “the trends we identify… are likely to act as a tailwind, putting some of Canada’s provincial/territorial and municipal political parties and politicians, electoral activities and relevant media under increasing threat.”

Despite this, Ontario is imposing automated counting precisely at a time when others are waking up to its hazards. Indeed, last year The Netherlands switched back from electronic voting to hand counting to eliminate the threat of hacking.

Traditional checks and balances within the Election Act would normally have protected our system from these hazards, but the government has found a way around them.

The Act clearly states: “the deputy returning officers shall open the ballot box and proceed to count the number of valid ballots cast for each candidate and all other ballots, therein giving full opportunity to those present to see each ballot and observe the procedure.”Outsourcing the count to computerstakes away this opportunity.

To cover itself, the government added a new section to theAct in 2016 that empowers the Chief Electoral Officer to impose the use of electronic vote-counting equipment, and modify the voting process, even in ways that conflict with the rest of the Act.

This new power removes two key protections in the Act. First, the ability of scrutineers to observe the counting process in the open provides public accountability at each polling station. Second, putting scrutineers in every polling station means that an impossibly large number of people would have to be corrupted to significantly distort the count.

By largely eliminating independent, direct observation of ballot counting, the government is creating unprecedented opportunities for interference. For example, participants at a major hacking conference last year found ways to manipulate electronic voting machines in mere hours.Other methods of compromising e-voting systems have been repeatedly laid out in both the popular press and in security publications.

Ontario’s Chief Electoral Officer has attempted to deflect these concerns by telling us that their security contractorshave tested the equipment.

Both the Liberals and the NDP are satisfied with the testing, according to the June 1 CBC report.

An NDP spokesperson was quoted as saying the agency “has provided all the parties with detailed information about the voting process and the counting machines.”

However, none of these details have been shown to the public.

Elections Ontario also is not subject to freedom of information requests.Therefore, the public has no way of knowing how important issues have been addressed. For example: What kinds of examinations were done on the hardware and software? How were offshore-sourced components checked for hidden devices designed to give control to bad actors? What checks will be in place on voting day to limit access to the machines’ removable memory cards that record the counts?

Without answers to these questions, we have no guarantee the June 7 official election results will reflect the choices made by voters.

But we can virtually guarantee that an attack will occur. Why? The software and hardware comes from a single source: the manufacturer. This centralises our previously decentralised system, creating a magnet for abuse. It provides an unprecedented opportunity to corrupt the entire count by controlling just one target.

Look no farther than the 2017 hack of the Equifax credit-rating agencyto see what happens when you centralise control over data.The financial information of 150 million people was compromised, despite Equifax having world-class cybersecurity resources.

In the face of all these problems, Elections Ontario still expects our trust despite its own difficulties in securing voter data.

Any government that is genuinely interested in election integrity would restore scrutineers’ rights, or at least implement sensible checks such as risk-limiting audits.

On the same note, if the public believes election integrity is more important than convenience, we must speak up. When candidates come knocking at your door, tell them you don’t trust computers to count your vote.

Howard Pasternack is an engineer in Toronto. Rosemary Frei is an activist and journalist in Toronto.

Photo: Dominion Voting Systems

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.