Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

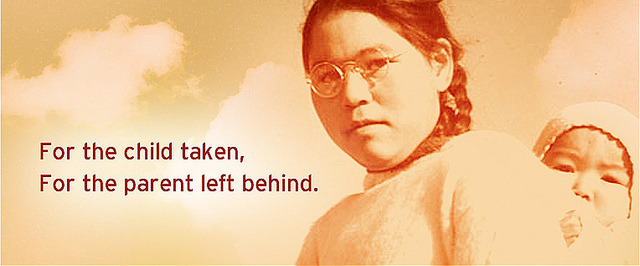

In a long-awaited ruling, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal finally confirmed what many have known for decades. The federal government provides less funding for child welfare services for First Nations children living on reserves and in the Yukon than it does for non-Indigenous child populations. Declaring this a case of racial discrimination, the tribunal ordered Ottawa to “cease the discriminatory practice and take measures to redress and prevent it.”

While taking some time to celebrate this victorious outcome, we should nonetheless understand that this victory is double-edged. It obscures the bigger picture. From its inception, the child welfare system has never worked in favour of Indigenous peoples. On the contrary, as a supplement to and later substitute for the Indian Residential School System, the child welfare system has wreaked havoc on generations of Indigenous peoples. And it continues to do so in the present.

Indigenous children continue to be removed en masse. The rate at which Indigenous children enter the child welfare system has been on the rise ever since the now infamous “Sixties Scoop.” In 2011, according to Statistics Canada, despite constituting only seven per cent of the overall child population, almost half (48.1 per cent) of the children under the age of 14 in foster care across Canada were Indigenous children.

Equally alarming is the fact that the death toll for Indigenous children in child welfare custody is also more pronounced than for their non-Indigenous peers. The problem — the large-scale removal of Indigenous children through the Canadian settler state — should not be reduced to one of unequal funding. This issue is larger than merely rectifying a discriminatory practice within a seemingly egalitarian system.

Child welfare laws manage the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the settler state. This relationship normalizes the settler society’s position over Indigenous peoples. Through this framework, the Canadian state possesses the unquestioned rights to enter Indigenous communities, judge the welfare of their children, and remove them as they see fit. The leading factors that cause Indigenous children to be removed from their homes are the very material conditions (such as poverty) that are a direct outcome of colonialism past and present.

Even as we remember that child welfare is a central part of the ongoing colonial management of Indigenous peoples, it is still immediately necessary to overhaul the funding schemes Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada uses to fund First Nations Child and Family Service (FNCFS) Agencies and child and family services in Ontario.

For one, as substantiated by the tribunal, the current model consistently provides less funding to First Nations children than non-Indigenous children. Secondly, the funding that is provided is directed towards child apprehension rather than prevention services (such as family support), resulting in higher levels of institutionalization of First Nations children. Two very good reasons to do away with it.

Why we need a court order to rectify such blatant inequality should give us pause. It should be noted that these dynamics are not news to the federal government. Already in the 1980s, the Canadian Council on Social Development identified the constitutional jurisdictional split between the federal government and the provinces and territories (which the current FNCFS funding model is a result of) as causing uneven social services for First Nations on reserves.

And prior to the implementation of the FNCFS funding schemes, Indigenous peoples informed the federal government that if it were implemented as suggested, their children would be funneled into child welfare institutions due to its prioritization of child apprehension over prevention services. The federal government proceeded anyway.

This long-standing impulse to discriminate will not go away with one court order for the simple reason that it begins in a colonial structure. Equal funding within a fundamentally unjust system, cannot lead to justice.

Strategic improvements to the child welfare system are certainly necessary in the interim as they may lessen the detrimental impact the child welfare system has on Indigenous peoples. But for the long-term, let us think beyond such narrow definitions of justice.

If the problem is colonialism, then the answer is decolonization. Solutions that are disconnected from Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty and self-determination can only go so far, and worse of all, may even enable us to believe that we have done our best.

Reacting to the Human Rights Tribunal decision, Justice Minister Wilson-Raybould proposes a nation-to-nation relationship as a possible way forward. What such a relationship can look like is something we need to think about.

Laura Landertinger is a PhD candidate in the department of Social Justice Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto. Her work examines the intersections of race, gender and settler colonialism in Canada, focusing in particular on the institution of child welfare.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Flickr/Neeta Lind