“As an ordinary Canadian I feel deeply that this wonderful country is at a crucial, and very fragile, juncture in its history. One of the major reasons for this fragility is the deep sense of alienation and frustration felt by, I believe, the vast majority of Canadian Indians, Inuit and Métis. Accordingly, any process of change or reform in Canada — whether constitutional, economic or social — should not proceed, and cannot succeed, without aboriginal issues being an important part of the agenda.”

– The Right Honourable Brian Dickson, Report of the Special Representative respecting the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1991)

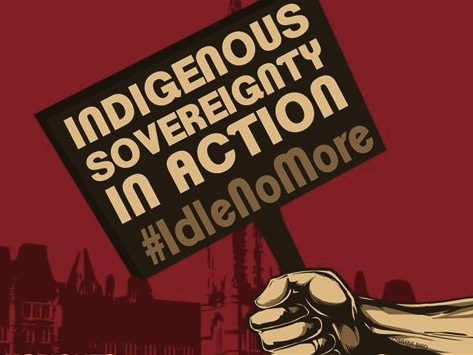

The demands of the protesters led by Idle No More have a familiar ring. Like today, Canadians became aware “something was wrong” when Aboriginal issues exploded in the media.

Shortly after the end of the Oka Crisis in 1990, the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney asked former Chief Justice Brian Dickson to consult with Indigenous Peoples and their leaders as well as experts and federal and provincial politicians. From these consultations came the mandate of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), which was charged with examining the historical and contemporary relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians and to make recommendations on how the relationship could be improved.

Former Assembly of First Nations Grand Chief George Erasmus and Justice René Dussault of the Québec Court of Appeal, co-chaired the Commission, which had a comprehensive — some said impossible — mandate.

Mr. Justice Dickson wrote that the Royal Commission “should investigate the evolution of the relationship among aboriginal peoples (Indian, Inuit and Métis), the Canadian government, and Canadian society as a whole. It should propose specific solutions, rooted in domestic and international experience, to the problems which have plagued those relationships and which confront aboriginal peoples today….”

The Commission ran from 1991 until 1995. During this period, the Liberals under Jean Chretien replaced Mulroney and the Conservatives.

A generation has passed since the RCAP was established and its major findings and recommendations resonate today as the Idle No More movement draws global attention and the Harper government struggles to grapple with an issue not on its carefully managed agenda.

The 4000-page RCAP report contained more than 400 recommendations and was released in the magnificent Grand Hall of the Museum of Civilization in November 1996. The co-chairs called it “a new beginning… Our report proposes a comprehensive strategy over 20 years to restore social, economic and political health to Aboriginal peoples and rebuild their relationship with all Canadians.”

In front of hundreds of people and banks of television cameras, the co-chairs said, “the legacy of Canada’s treatment of Aboriginal people is one of waste: wasted potential, wasted money, wasted lives.” It was time to turn a new page.

Among RCAP’s main recommendations was an Aboriginal Nation Recognition and Government Act to establish “a process and criteria for the recognition of each Aboriginal nation, acknowledge its immediate jurisdiction over ‘core issues’ within its existing territories, and provide interim fiscal arrangements to help finance self-government.”

It also recommended an Aboriginal Treaties Implementation Act to enable “a recognized Aboriginal nation, in negotiation with other Canadian governments, to renew its existing treaties or create new treaties to establish its full jurisdiction as a member of an Aboriginal order of government and establish or expand its land and resource base to foster self-sufficiency and create a home for its people.”

An Aboriginal Parliament Act would establish a body to represent Aboriginal peoples within federal governing institutions and advise Parliament on matters affecting Aboriginal people. Eventually, this would lead to “a House of First Peoples to take a place in the governing of the country alongside the House of Commons and the Senate.”

In making the case for why change was needed, the Commission’s stated:

We believe firmly that the time has come to resolve a fundamental contradiction at the heart of Canada: that while we assume the role of defender of human rights in the international community, we retain, in our conception of Canada’s origins and make-up, the remnants of colonial attitudes of cultural superiority that do violence to the Aboriginal peoples to whom they are directed. Restoring Aboriginal nations to a place of honour in our shared history, and recognizing their continuing presence as collectives participating in Canadian life, are therefore fundamental to the changes we propose.

The Commission called for “restorative justice by which we mean the obligation to relinquish control of that which has been unjustly appropriated: the authority of Aboriginal nations to govern their own affairs; control of lands and resources essential to the livelihood of families and communities; and jurisdiction over education, child welfare and community services. As well, there needs to be “corrective justice, eliminating the disparities in economic base and individual and collective well-being that have resulted from unjust treatment in the past.”

Full Aboriginal participation in Canada society is not only a matter of justice, the report said, “opening the door to Aboriginal peoples’ participation is also a means of promoting social harmony.” The kind of harmony that is absent from the national landscape these days.

It’s time to revisit the RCAP report. The Commission had much to say about inclusion and the proper functioning of democracy. These are issues that Idle No More is talking about, and they are issues that concern all Canadians. The current protest grew out of concerns sparked by the Harper Government’s omnibus bill C-45 which contained not only the budget but also changed parts of the Indian Act, the Navigation Protection Act and the Environmental Assessment Act, among others.

The Idle No More movement has struck a chord with many Canadians who feel there is something wrong with the way the country is being governed. The frustration many Indigenous Peoples are expressing is, in many ways, symptomatic of a democracy that has lost its way. There are few opportunities for people to express their opinions other than a periodic trek to the polls.

Social movements remind us of an inconvenient truth, that we are responsible for the actions of our governments. If we disagree with the direction and decisions they make, then it’s up to us to set them on the right path.

John Crump is a CCPA research associate. He worked as a researcher, policy analyst and writer for the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.