It is my sincere hope that the next phase to Idle No More would be to bloom into a full civil rights movement; similar to what we have seen in history’s past.

Native Rights = Human Rights

I am taken aback by how much the current digital campaign of #MMIW to fight for the safety of Indigenous women and girls is similar to other campaigns in the past.

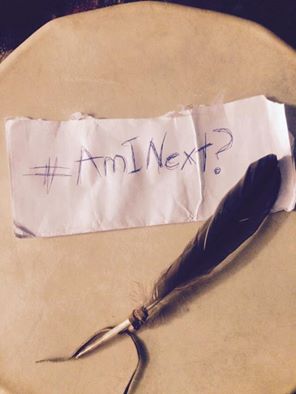

Currently on the Internet, there is a campaign called #AmINext which strips away any safety-of-a-faceless-victims that the viewer can hide behind.

Indigenous women and girls have been using social media to post humanizing photos of themselves stating simply – in that simply beautiful way a few words can express a huge idea – “Am I next?”

“Am I next to be murdered or disappeared?”

“I will not be next!”

#ImNotNext

It is the: I am not the next statistic. I am not the next to have my blood spilled on the backseat of some guy’s car, in my own home or on the streets.

Banding together while preserving individualism and diversity at the same time is a tricky balance women are traditionally better at pulling off as part of the Idle No More and Am I Next campaigns.

Am I Next? reminds us that Indigenous women and girls are persons, someone you could look in the eye, shake hands with, donate blood to; not simply an extension of the lumpen proletariat or a sociological or criminal statistics.

“I AM A Indigenous Woman”. “I AM A Indigenous Girl”.

And in of itself, I have rights.

Because I Am. I exist.

Of course, we need to stymie any notions of patriarchal behaviour here since it’s a slippery slope to White Knight Syndrome.

Writes Sarah Hunt, “As Indigenous people, our refusal to be portrayed as victims must extend to all members of our communities, including youth, sex workers and many others whose ‘vulnerability’ is all too often used as an excuse for colonial interventions into our homes and communities. We need to remember it is the systems and ideologies of colonial society that make us vulnerable, not our Indigeneity, our age, our sexuality, our ability, nor how we make a living.

This “I am” is limitless: I am a mother, a daughter, an aunt, a friend, a grandmother. This “I am” is not a sociological ‘other’; not garbage strewn across the side of a highway or laying at the bottom of a river.

The move to band together and humanize their experience and struggle reminds me of a similar strategy employed during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

The times and method of communication are different – placards not hashtags – but the underlying emotions and understanding in the same.

The campaign for civil rights was also beautifully simple: “I Am a Man!” is a declaration of civil rights, often used as a personal statement and as a declaration of independence against oppression.

The declaration came as a strategy for social change during the emancipation period – as United Kingdom and United States’ abolitionists used, “I am not a man and a brother?” as a slogan in their effort to bring about the emancipation of African and Caribbean slaves and halt the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

This theme of the importance of recognition of a person – for example, legally as having habeas corpus in the court system for both the emancipated African Americans, and Native Americans – allowed people to intrinsically and systematically be recognized as having worth.

Unfortunately, the passage of time did not automatically solidify someone’s recognition of personhood – whether a woman, an immigrant, someone Indigenous or freedman or freedwoman.

For example, the judicial case of Dred Scott vs. Standford brought forward a case that attempted to clarify defined personhood back into the spotlight.

The question of “Am I Not A Man and a Brother?” let to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling to decide whether a Free and/or Slave male could in fact be considered a person and could therefore sue the courts for his freedom.

Dred Scott, an enslaved African American man who had been taken by his owners to free states and territories, attempted to sue for his freedom. In a 7–2 decision written by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, the Court denied Scott’s request. He was to remain a slave despite the fact of living in a ‘free’ state.

The question was raised again during the American Civil Rights Movement at the Memphis Sanitation Strike which started on February 11, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee.

After years of poor treatment and dangerous working conditions, around 1,300 African American sanitation workers walked off the job; while also seeking to join a union.

The incident that triggered the strike was the death of two black, male employees – Echol Cole and Robert Walker. Cole and Walker accidentally died when they were crushed to death after sitting among the garbage in the back of their compressor truck, the only place they were allowed to stay dry by a Memphis City bylaw that forbid them from seeking shelter from the rain anywhere but amongst the garbage.

During the strike, black men wore A-sign placards that read: I AM A MAN.

This is why we need to move from Idle No More to a full civil rights movement here in Canada for no other reason than simply uniting Canadians together in the binding, legal and human understanding that how we treat an Indigenous woman can be no different than we treat a white woman.

I feel one of the only reasons why the death of almost 2,000 Indigenous women and girls has not prompted more of a public outcry and appropriate government action is racism.

We all have questions to ask ourselves:

“Are they not women?”

“Do they not deserve justice?”

It is the concern for the community and the concern for the fate of the self – the “I” in the question posed – that reminds us of the humanity we all share. We are all one.

Supporting the call for justice and an end to the murder and disappearances of Indigenous woman and girls is to be on the right side of history.

**

Please use this link to find a Sisters in Spirit Vigil near you and come out on Saturday October 4, 2014.