Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

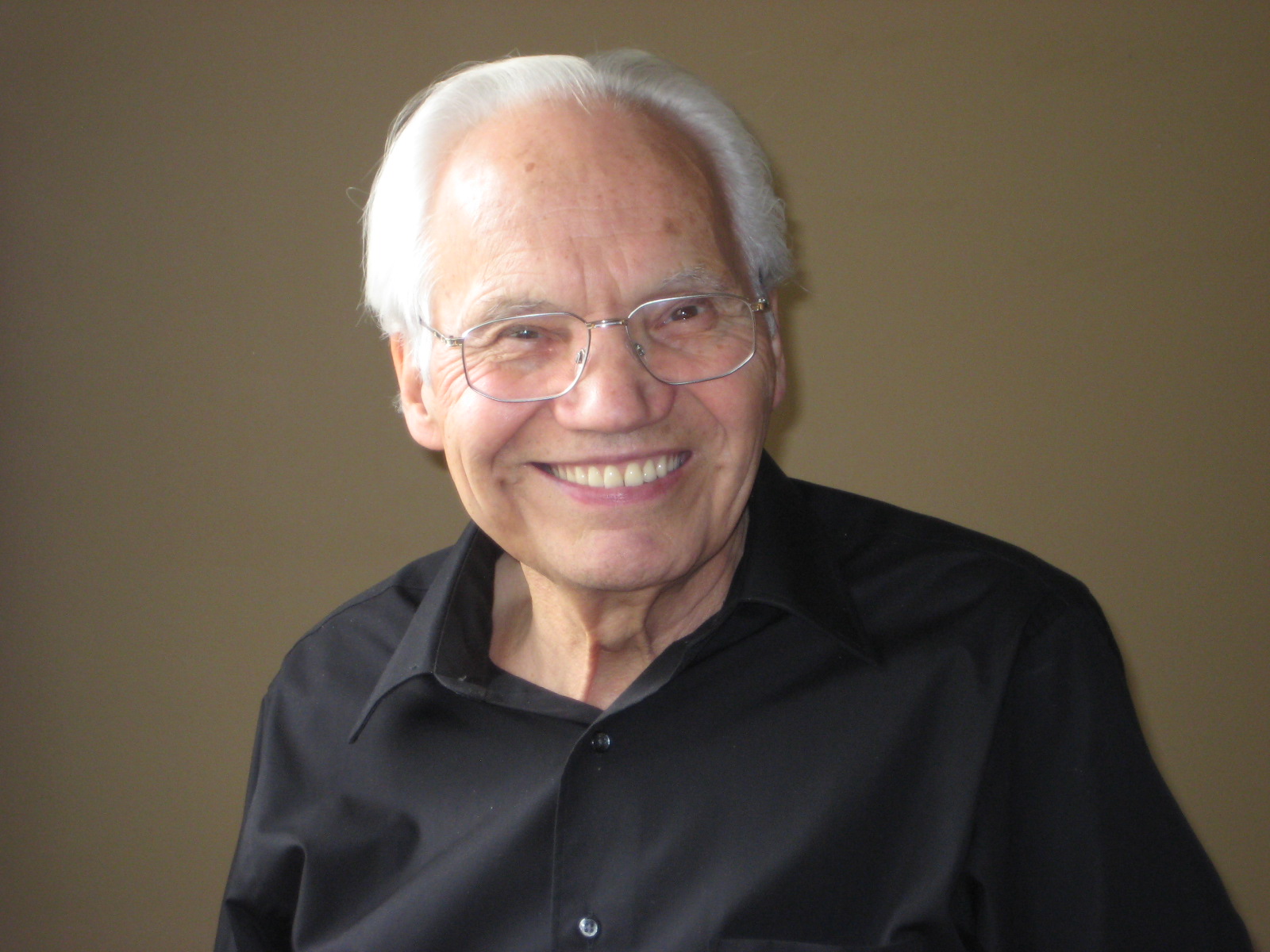

My hero and longtime friend William Wutunee has gone to meet the Creator at the age of 87. Or maybe not. Although Bill was a shaman who sometimes donned his eagle feather headdress to lead our Unitarian congregation in healing circles, he was also an intellectual who enjoyed reading atheist Richard Dawkins and debating his talking points.

Bill’s life changed Canada, not just for Native people, but for all of us. He was:

• the first Native lawyer in Western Canada,

• a friend and political ally of Tommy Douglas,

• an early defence lawyer on human rights issues such as homosexuality,

• a key person in convening the first national Chief’s conference (and the first national Chief),

• and above all, an Assembly of First Nations strategist around the issue of residential schools and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

I’ve known Bill for more than a decade, as well as his daughter Nola, a former anchor person with cable TV network APTN, and some other members of his family. I’m glad he lived to see the TRC deliver meaningful recommendations, even with the discomforts of his worsening health. I am posting the article I wrote for the Spring 2009 issue of Legacy magazine, another treasure Albertans have lost.

Ruffled Feathers

Helping to set up Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is just the latest work in Cree Elder Bill Wuttunee’s lifetime of activism on behalf of Native people, and indeed, of all Canadians who face discrimination.

Bill was born in 1928 and grew up on a farm on the Red Pheasant Reserve in Saskatchewan. His parents, James and Jane Priscilla Wuttunee, were both well-educated for their time. James earned the equivalent of a Grade 12 diploma in the early 1900s, when few Canadians attended high school at all. The couple ran a small mixed farm, with livestock as well as crops. During the Great Depression, they had plenty of food and intellectual stimulation to share with their 13 children, of whom four died young, and only four are still living.

When he was 12, Bill said, he was reading Hansard report on the joint House-Senate committe on Indian Affairs, and came across a case where a lawyer told Indians they were “estopped” from making their presentation. He taunted them that they did not know what “estoppel” means. Bill vowed he would become a lawyer, and defend his people. He was called to the Bar in Saskatchewan in 1952, thus becoming the first Native lawyer in Western Canada. And he fulfilled his childhood vow in 1959 when, “I appeared before that very same committee,” he said, “and I was a lawyer, and I could answer any question they asked.”

In 1958, (then) Saskatchewan Premier Tommy Douglas asked Bill to work on the Provincial Committee on Minority Groups. That summer, Bill visited 56 Indian bands across the province and organized a conference on the topic of what the province could do for Natives. When the band representatives voted to ask for provincial voting rights and access to liquor, Tommy Douglas promptly introduced the legislation to grant their requests.

“So that’s how all the provinces began to get involved with Indians,” Bill recalled. “And the next year, the federal government passed a law so that Native people could vote across Canada.” Bill spent the next few years working on getting electricity and then telephone services to the reserves. Saskatchewan Telephone didn’t want to put a phone on a reserve because they said nobody would pay the bill. “So I said, put in a pay phone,” said Bill, “and they did.”

In 1962, Bill moved to Edmonton to work for the Canadian Citizenship branch — for one year. “I was fired because I’d been talking with Indians about independence,” he said. “I never made a fuss over that. But at the same time, there was a fellow named Marcel Chaput, in Quebec. He was fired at the same time, for advocating independence for the French. He made a fuss, and that hit the papers.”

Bill decided to set up his own law practice in Calgary handling criminal cases and family law. “I didn’t know anybody here. I came here because the weather was nice and the people seemed nice, and I’ve never been sorry. Alberta has been good to me, and good for my family.” Bill and his first wife, Bernice, raised five children together, all of whom now follow professional occupations, in academia and education, media, law, and the civil service. He and his life partner, Rose, have a son who is a lawyer.

In 1966, Bill opened a branch office in Yellowknife, where one of his cases was to defend Everett Klippert in a case that led to changes in the law against homosexuality. Charged with “gross indecency” because he admitted to having had sexual relations with four separate men, Klippert was sentenced to “preventive detention” (that is, indefinitely) as a Dangerous Sexual Offender. He served five years, while his appeal worked its way through the courts to the Supreme Court, where it was finally dismissed in a controversial 3-2 decision.

Then Tommy Douglas raised the issue in the House of Commons and, within six weeks, Pierre Trudeau introduced changes to the Criminal Code, decriminalizing homosexuality. Said Bill, “Trudeau cited the Klippert case when he said that the state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.”

At 81, Bill Wuttunee seems to be a bundle of contradictions: thoughtful and intellectual, yet playful and unpredictable; living among French Provincial furniture and wearing Holt Renfrew sweaters, yet proudly rooted in his Native history and traditions. Although he no longer practices law, he keeps busy. To name only one among his many pastimes, he researched and compiled an extensive Cree grammar, and plans to put it on a website someday.

Bill’s home office boasts a state-of-the-art videophone, in addition to a computer and fax machine. He is promoting the idea that every remote reserve community needs videophones, so people there can participate in conferences, and their schools can receive classroom instruction onscreen.

He still has some pull with the Assembly of First Nations. In fact, as a representive of the AFN advisory group, Bill helped shape the federal government’s response to the tragic effects of the Indian Residential Schools. Bill is a residential school survivor himself — he attended the Onion Lake Residential School for two years in his teens, so he knows what the issues are and (in a very real sense) where some of the bodies are buried.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is largely a fact-finding panel, with a mandate to document what it learns from survivors and make their experiences part of the public record, although exactly how they will accomplish that has yet to be determined. “We want a research centre, with the records from the government and churches. And some of us had the idea to set up memorials. I would like to see museums in different locations across the country,” said Bill. “Some of our planners have suggested films, written work, songs, places to display pictures.”

Meanwhile, the TRC operates under specific guidelines and parameters. For example, most hearings will be held without any public or media attention. “Every time we have meetings, people need [medical] attention. Even remembering and talking about what happened can be very emotional,” said Bill. “One man in Montreal passed out.”

Despite the horrific nature of some of the complaints about the Residential Schools, the Commission is not an investigative body and has no authority to charge anyone with crimes. However, Bill pointed out that there is a separate tribunal to deal with charges of abuse. He also mentioned that he had heard the RCMP might follow up on some TRC complaints.

Bill is most troubled by the approximately 55,000 missing children who were recorded as picked up but who never returned to their homes and parents. “Some may still be alive,” he said hopefully, “but there are a lot of witnesses who say they buried residential school children in unmarked graves. Just imagine — 55,000 children died, or maybe were adopted out, at a time when the census shows our people numbered only about 100,000.”

Although Bill helped set up Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings all across Canada, he pointed out that about two-thirds of the residential schools were here on the Prairies. He had input in selecting the lawyers who will be involved. “There are two thousand Native lawyers now,” Bill said. “Imagine that!” And he helped create the format: “I urged them to honour Native traditions — for example, to have witnesses hold an eagle feather instead of swearing on the Bible.”

The TRC received national media attention in October, when Justice Harry S. LaForme abruptly resigned as Chief Commissioner. Bill flew to Ottawa and took part in some of the news conferences about the unfortunate turn of events. Later, he said that Mr LaForme could truthfully have cited his health as the reason he was stepping down. He shrugged. “These kinds of problems are not unusual in such Commissions. There have been other Commissions set up, in Australia, in South Africa, in Peru, in Chechnya, in East Timor. They’ve all had similar problems.”

In mid-November, Bill spoke publicly about the TRC and about his own experiences in residential school, and he revealed experiences that his family in attendance said he had never spoken about with them before. “I came from a reserve that had lots of land, more than 36,000 acres,” he told the congregation of the Unitarian Church of Calgary. “We could do anything we wanted. We could go horseback riding. We could gallop across the plains. We could go hunting. And we had good parents, they cared for us, they weren’t disciplinarians. Then one day, a Black Mariah drew up, and all the kids got in there, and a white guy took us off to Onion Lake, to a three story brick building, where we had to line up for everything.

“There was one bathtub, for about a hundred boys, and two or three showers, and about eight toilets. One time I saw a little boy being strapped. I had a wrist watch on at the time, and I looked at my watch. And do you know, that little boy was strapped for 20 minutes, on his bare arms. Sometimes people who were punished tried to run away. And if you ran away and you got caught, you were severely punished. My brother Paul ran away, with some other boys, and the RCMP brought them back. They were stripped naked, and whipped a hundred times. Then they had their hair cut off, and they were put in dresses.”

As Bill described some of the unspeakable behaviour that went on in residential schools, listeners could only shake their heads numbly. Finally he asked, “What can we do about it now?” and he answered, “We have to trade our tears of sadness for tears of joy, for the people who were put to great distress, at a time when they were only children. Those children became parents, and passed all their unresolved stress unto the next generation. We can now show the oppressed, and the oppressors, that we can work together to bring about reconciliation.

“The Commission has the task of bringing about this reconciliation, so that all Canadian participate in it. And how do we do that? This is part of it, sharing the story. You’re listening to me talk, and you feel sad, and you wonder what you can do….”

“The plans to destroy an indigenous nation so their lands could be taken over by the settlers have been done all over the world, for instance the British in India, and continues to happen here and in other countries. This is done because of greed, and selfishness, and the search for gold, land, minerals, at any cost. But the native people don’t amass wealth, like other people do. We have enough in our land, in our lives, and the people and animals around us, and that’s the big difference. As time goes on, I’m sure we will have similar values. You will learn from us, and we will learn from you.”

Post-script

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is one aspect of a $4 billion court settlement reached in December 2006, as a result of a class action suit that the Assembly of First Nations filed in August 2005. The AFN Task Force had been collecting evidence on the Indian Residential Schools since 1998.

Residential schools operated for about 100 years, starting from the 1850s. For several decades in the early to mid-1900s, federal law required all Aboriginal children aged 7 to 15 to attend Indian Residential Schools. This aspect of the 1857 “Gradual Assimilation Act” was strictly — sometimes brutally — enforced. RCMP, priests and Indian agents literally tore children from their parents’ arms, and sent them away to distant schools run by the Catholic or United Church, where the children were forbidden to speak their own languages or hug their own siblings. Most students found the experience traumatic, to say the least. Few of them ever did assimilate into the larger society.

In the 1980s, former residential school students began disclosing that they had endured physical and sexual abuse at the schools. The Assembly of First Nations struck a task force that reported in 2005, “There are approximately 87,000 residential schools survivors still alive in Canada. The average age of survivors is 57 years old. The government has an ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution’ process in place, but at the current pace it will take 53 years to settle all claims, at a cost to Canadian taxpayers of $2.3 billion dollars in administrative and legal expenses alone.” Instead of waiting 53 years, the AFN launched a class action suit on behalf of the survivors.

Under the class action settlement reached in 2006, every Indian Residential School survivor is eligible to receive a Common Experiences payment of $10,000, plus $3000 for each year of school, and to be individually assessed for more benefits. In addition, there are funds for commemorating what happened, for an Aboriginal Healing Foundation, and for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.