We carry a lot with us.

We carry our stories, our loves, our histories, our traumas, inside ourselves every day. And they are heavy. They sometimes weigh on our hearts and take up residency in the back of our brains. Sometimes they make our bones ache with their presence.

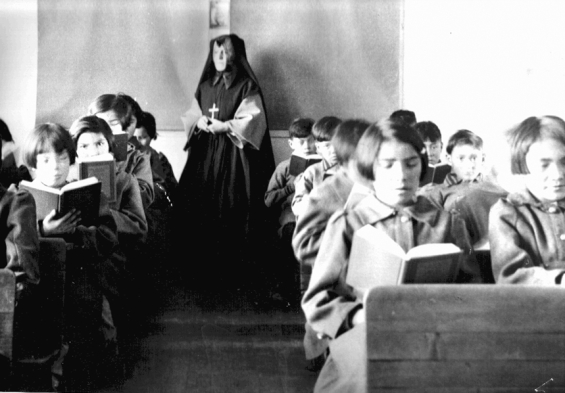

The term reconciliation is something I carry with me everyday. It makes my heart heavy and my bones ache. I have talked extensively about storytelling and the duty we have to tell our stories and protect our stories and about how we carry our ancestors’ stories with us. I have a duty to my kokum as her granddaughter: I carry her stories with me and her stories include her being a residential school survivor. Though I carry her story with me, a story that beats with every heartbeat, I do not believe it is my place to tell her story. It is hers to share if she wants to.

You see, my kokum is a fierce Metis lady. She’s a force of nature and someone I am truly honoured to share life with. She is unbreakable. She has this hilarious, crass sense of humour you would not expect out of a tiny Elder. She is someone who has such a compelling spirit that when I found out she had been through the residential school system, I honestly could not place these atrocities in her life.

Around the time I learned my kokum had attended Residential School was the time she was filling out all the paperwork for the settlement. This is when we found out that the Ile-a-la-Crosse school was not included, that Metis survivors were left out of this grand process of apology and reconciliation. This is also when I heard Metis Elders, my Elders, from across the country start the lay their traumas out for the world to hear. Because a process was created that measured abuse in dollars and called it an apology. So I heard Metis Elders yell their abuse in order to be legitimized. I listened to my kokum rehash her abuse so she could be a part of this grand act of reconciliation.

I want to reserve a moment to honour that this process was healing and powerful for some Survivors and I do not mean my words and feelings to neglect this.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission coming to conclusion and our era of reconciliation starting, I can not help but feel like my family and other Metis families have been left out of this process. Metis representatives were excluded from the closing ceremonies of the TRC , schools that were in Metis communities were excluded from the agreement, and from my own experience calling 1-800 numbers and talking to representatives at commission events that Metis peoples were uncomfortably excluded in many ways.

I obviously can not speak for Metis survivors, but as someone who has lived with this reality in her family I am unreconciled. I will stand in support of survivors and this process that has happened, but I cannot do so without my kokum‘s stories taking up space in my heart and making it heavy.

I carry my kokum with me. I carry the Metis elders who have been left out with me. State-mandated reconciliation that left out peoples who have been violated by the state is not reconciliation, to me.

I still do not understand the extent of intergenerational trauma, but I read somewhere that we carry our ancestors’ memories in our DNA. I will never understand the extent of the abuses my kokum faced in residential school or the violence my ancestors faced through violent dispossession of our communities and from diaspora. I do know that these are things I carry with me and these are things that my children will carry with them. I do not want this to be a burden, I do not look at it as a burden, but I do not look at it as something that has now been reconciled with the close of the TRC. I do not feel calmed or feel that I can pass down a legacy to my future children in a good way.

I am proud of survivors who told their stories and reached out through the Truth Commission process. I feel honoured to have been witness to their stories. But I feel for myself, for my family, for our communities, we are not healed.

I do not have the answers or a vision of a solution. But I know that even though I carry my kokum’s trauma and stories with me through her experience, I also carry her immense love and crass sense of humour too. Every now and then I have to remind myself that we are not our traumas, we not just an accumulation of the hurt and pain that we have experienced. We are also resistance, resilience, tenderness, and power. We are all our most beloved memories, memories that make our heart just that much lighter. We are the memories that make us laugh till our bellies hurt and our eyes crinkle at the sides.

We carry a lot with us throughout our days, and it is taxing and it is hard. But I think we need to remember, especially given our recent times, to be tender with ourselves. To give ourselves space to grieve and vent but also space to practice radical self love. We have to protect the memories we carry in us, even the ones that hurt.

Image: From the Edmund Metatawabin collection at the University of Algoma, via Wikimedia Commons.