In the words of Justice Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), “Reconciliation is about forging and maintaining respectful relationships.”

But Canada has shown little respect for the Indigenous peoples of this land.

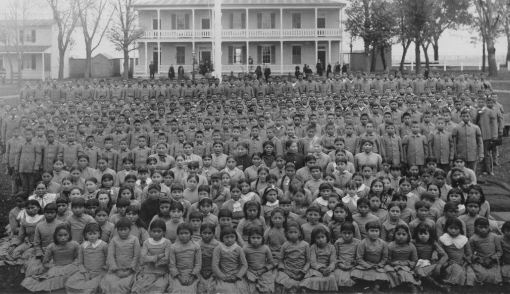

Between 1880 and 1996, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were compelled by law to attend residential schools run on behalf of the Government of Canada. These schools were a central tool in the policy to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people into another culture. Stated simply by one of those most responsible for its implementation, the goal of residential schools was “to kill the Indian in the child.” To achieve this goal, children were forbidden to use their language, practice their religion or see their families. Punishment for breaking the rules was severe.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was created as part of an out-of-court settlement in a class action lawsuit over the physical, psychological and sexual abuse that resulted, inevitably, from this dehumanizing policy.

In Edmonton at the end of March, the TRC held its seventh and final public event, bringing the formal process for gathering statements to a close. The University of Manitoba will house the voluminous record that is being collected and the TRC will publish its report in June of 2015.

Through the hearings, survivors and their families have been able to tell their stories publicly, often for the first time, and this has provided a form of healing for many. Their testimony also brings insight for those who make the effort to listen. These are important results.

The TRC is doing a difficult job with dignity, compassion and professionalism. Yet it will at best get at only a portion of the truth and assist a relatively small group of people in reconciling with their own past.

Even within the limited terms of the TRC’s mandate, parts of the story remain unexplored. The perpetrators of abuse were not compelled to testify at hearings. The number of children who died in residential schools is unknown, the reasons for their deaths obscured, even the burial sites of many remain a mystery. The extent to which scientific experimentation, deliberate malnourishment and other crimes against humanity were perpetrated likely will never be fully admitted.

As if to demonstrate the insincerity of his own apology for residential schools, Prime Minister Harper’s government squanders time, money and good will fighting against allowing the truth to come out. The TRC twice has had to take the government to court just to get available information on the public record.

And, there has been little attention from the rest of Canada. Some people of influence have attended the hearings — Joe Clark and Tom Mulcair were in Edmonton for example — but the public is not engaged, treating this as an Indigenous issue.

Meanwhile, broader questions regarding assimilation policy and its continuing application may not even be broached.

The failure to confront our shared past means that we will remain unable to build a common future.

Most Canadians have little understanding of the history of this land and its people. They have still less understanding of how that history relates to the conflicts we face today.

When I was in school, the mainstream education system — the flipside of residential schools — taught a false, self-justifying version of history, relegating the realities of Indigenous life and the legalities of Indigenous rights to the dustbin. In a form of self-fulfilling prophecy, the belief that Indigenous cultures would eventually fade away through assimilation was made manifest by pretending in our schools that it had already happened. Popular culture and media, owned and operated almost exclusively by those who have benefited most from this lie, serve to buttress these false teachings.

While there are signs this situation is slowly changing, the result has been concealment of the truth and continuing colonization.

As a result, reconciliation — a goal legally mandated by more than one Supreme Court of Canada decision — remains misunderstood and elusive.

For many Indigenous people, the term is losing appeal as they come to see in it an expectation they will reconcile to the mainstream culture without reciprocation.

The respect on which reconciliation relies remains absent from public attitudes toward Indigenous peoples and from government actions contradicting Indigenous rights. And for many Indigenous people in this country, the feeling is mutual.

It would be unfair to expect the TRC to have tackled questions beyond the topic of residential schools. But it would be a greater mistake to believe that its process should be the end of the discussion. There is much more truth to uncover and a very long way to go before we all reconcile ourselves with it and with each other.