If you know who you are, you will be able to treat others with respect. This is one of the key messages of Justice Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada. The TRC is charged with raising awareness among Canadians of the Indian Residential School legacy.

Knowing who you are is about both individual and collective identities. Knowing who we are as Canadians means acknowledging and understanding the injustices and harms experienced by Indigenous people at the residential schools. Yet many Canadians have never heard of the schools, and have no idea that they were part of a government plan to absorb First Nations, Inuit and Métis people into the dominant culture by removing the children from their families and communities.

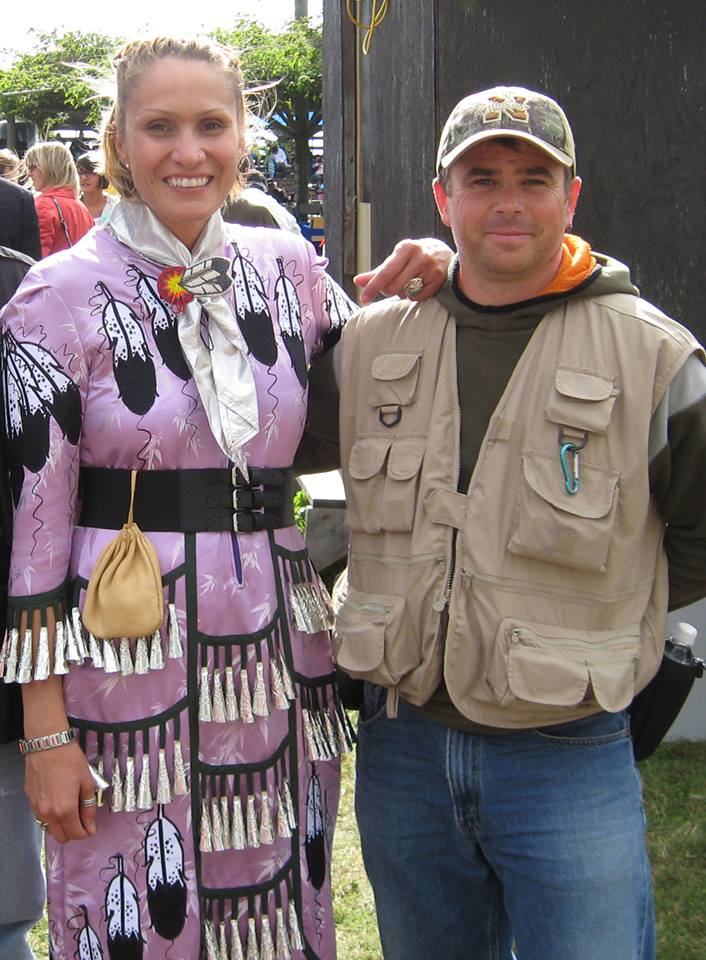

At the Alberta National Event of the TRC in Edmonton last month, Justice Sinclair’s words came to life for me in a relationship I was privileged to witness; a relationship between two people whose respect for each other deepened as James learned more about Jules through a shared experience of making a film together. Jules Koostachin, a Cree from Attawapiskat, and James Buffin who is non-Indigenous, met in the early 2000s in Toronto. Jules is an intergenerational residential school survivor. At the time she was starting a healing journey, and James, a filmmaker, was documenting it. The result is Jingle Dress: First Dance, a film that premiered at the TRC in Edmonton. Both Jules and James were at the screening and spoke about their experience making the film.

The film shows the strong bond of love shared by Jules, her mother and her grandmother. But it also shows the pain carried by these three generations of Indigenous women. To provide an opportunity for intergenerational healing, Jules involves her mother and grandmother as she learns about the jingle dress, commissions someone to make one and dances in it for the first time. The jingle dance is a healing dance that originated with the Ojibway people at Whitefish Bay, Ontario. It has since been gifted to all Indigenous people who carry the teaching of the dress with integrity. In the film, Jules and her mum say a prayer for each of the 365 jingles that are sewn onto the dress.

Meanwhile, through making the film, James, for the first time, learns about residential schools and the deep impacts they have had on families and communities. He undergoes his own journey, realizing how different he is from Jules, due to background, despite having a lot in common. He learns that he is part of a country that developed a system to forcefully eradicate Indigenous cultures, and that his friend has been on the receiving end of that policy of assimilation. In learning more about his identity as a Canadian he is able to more fully respect where Jules is coming from. Tens of thousands of people have attended the seven TRC national events and countless community hearings over the last five years. While the veil of silence and denial of this legacy is finally being lifted, our national narrative as a shining example of a country that respects human rights remains strong even though the pervasive and systemic discrimination against Indigenous children that allowed for residential schools to operate for over a hundred years continues.

If we are to move forward as a nation that truly upholds and defends the rights of all people, we must acknowledge this part of our shared history and understand how it shapes us. Only by accepting this truth will it be possible to realize a new, respectful relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Katy Quinn is the Indigenous Rights Program Coordinator at KAIROS: Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives.