After months of discussion with the Ontario and Federal governments, Ford Motor Co. has decided to take its engine investment elsewhere.

The global engine deal would have brought roughly $2 billion of investment to manufacture 1.5 and 1.6 Litre engines. It would also have created over 900 jobs and secured the future of engine manufacturing in Ontario for the next decade.

Speaking to CBC’s Amanda Lang, Unifor president Jerry Dias explained that the contract was originally slated for Mexico, but that the Union and the province were hoping to bring the contract north.

“We got involved with Ford a couple of months ago trying to wrestle it to Canada for our Windsor plants. We got together the government and gave it our best shot,” said Dias in the CBC interview.

After months of discussion, the federal and Ontario governments decided that they would not meet Ford’s $700 million requirement.

According to the Windsor Star, an anonymous government source says that the Canadian and provincial governments were willing to make significant investments, given the initial scope of the project. But the source believes that Ford never had any serious intention of making the investment in Windsor and that the whole process was Ford’s attempt to drum up more competitive offers from Mexico.

An accelerating ‘race to the bottom’

Canada’s failure to secure the engine investment is more than a lost opportunity, it’s part of an accelerating downward trend for the Canadian auto industry.

At the industry’s peak, Canada was the fourth largest auto producer in the world, assembling a record three million cars in 1999. Today, Canada ranks tenth and the industry has lost approximately one-third of its manufacturing footprint and almost 50,000 jobs.

Since the global financial crisis, car sales have been on the rebound in Canada and U.S., but the manufacturing industry has not.

Between 2010 and 2012, automakers invested $42.3 billion in North American plants. Yet only five per cent, or $2.3 billion of that investment came to Canada. According to a University of Windsor report, automakers invested almost $18 billion worldwide in 2013, and none of that money was spent in Canada.

Unifor economist Jim Stanford says that the tides won’t turn in Canada’s favour so long as our government continues to pursue an ad-hoc approach to industry development in Canada.

“It doesn’t make sense for the government to be trying to buy jobs with subsidies to companies with one hand, while signing more free trade agreements that gives all companies unconditional access to Canada’s markets with the other hand,” said Stanford.

“As long as the rules of NAFTA remain in place as they are, it’s going to take a hell of an effort by policymakers to win those investments in Canada in the future. And this disappointment on the Ford Engine is proof of that.”

‘Our enemy here is free trade’

Since the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, there has been a gradual southern migration of North American auto investment to Mexico, as the Canadian manufacturing industry shrinks and our economy becomes more dependent on imports.

With over $19 billion in new investment from foreign manufacturers including Honda, Nissan and Volkswagen, Mexico has one of the world’s fastest growing auto industry. In 2014 an estimated 3.2 million vehicles were manufactured in Mexico. Things going as they are, Mexico is poised to surpass Canada as the number one source of auto exports to the U.S.

With Mexican wages and benefits averaging at about $10 an hour, auto industries in Canada and the U.S. (excluding the non-unionized South) simply cannot compete with Mexico’s low cost manufacturing. Mexico is also well positioned for distribution to Canada and the U.S., as well as to the growing car markets in Southern and Latin America.

However, the growth of the Mexican auto industry will not contribute to higher wages in Mexico. To the contrary, given the competitive advantage of their low labour costs, it is the country interest to keep labour costs low, said Stanford.

“Free Trade was supposed to lift up Mexican standards towards ours, but in fact the current rules of the game are such that businesses, Mexican, American and Canadian alike, have a vested interested in continuing to suppress living standards in Mexico and that’s not going to change no matter how many auto plants move south.”

A tradition of state violence and “charro” or phony unions, not to mention overwhelming poverty, make it incredibly difficult for workers to exercise their rights or demand higher pay.

In addition to the downward pressure on wages and labour costs, governments are also expected to curry favour by providing cash subsidies, tax incentives, and free infrastructure and training.

While the $700 million dollars requested by Ford for the engine investment goes well beyond the 20 per cent that the Canadian government has traditionally made in auto manufacturing investment, the going rate in other regions can be as high as 60 per cent.

A continuing struggle

Unifor has called on the Canadian government to develop an integrated national strategy for the auto industry, one that could be tailored to stabilize other significant Canadian industries as well. Their suggestions include:

-

Develop a strong North American Auto Pact that would require companies to maintain presence in each of the NAFTA member countries as a condition of tariff-free access to the whole continental market.

-

Buy public equity in auto makers, as opposed to handing out cash subsidies, then use those equity stakes to leverage future investment. (20% of Volkswagen is owned by the state government in Germany and they haven’t closed a single plant in since the end of the World War Two.)

-

Support Canadian manufacturing and curtail automotive imports (which will only exacerbate by free trade agreements planned with the EU, Korea and Japan) to keep profits in Canada.

-

Build a Canadian car industry, with an emphasis on fuel-efficient “green cars.”

Furthermore, it is in the best interest of Canadian workers to build international solidarity.

“We’ve put a lot of energy in developing relationships with the Mexican unions and supporting them in anyway that we can, and we are absolutely in a charged struggle to protect the security and safety of living standards in both places,” said Stanford.

“Our preference is for a whole different philosophy for how to manage an industry like this so that everyone can genuinely have a share of the benefits.”

Ella Bedard is rabble.ca’s labour intern. She has written about labour issues for Dominion.ca and the Halifax Media Co-op and is the co-producer of the radio documentary The Amelie: Canadian Refugee Policy and the Story of the 1987 Boat People. She now lives in Toronto where she enjoys chasing the labour beat, biking and birding.

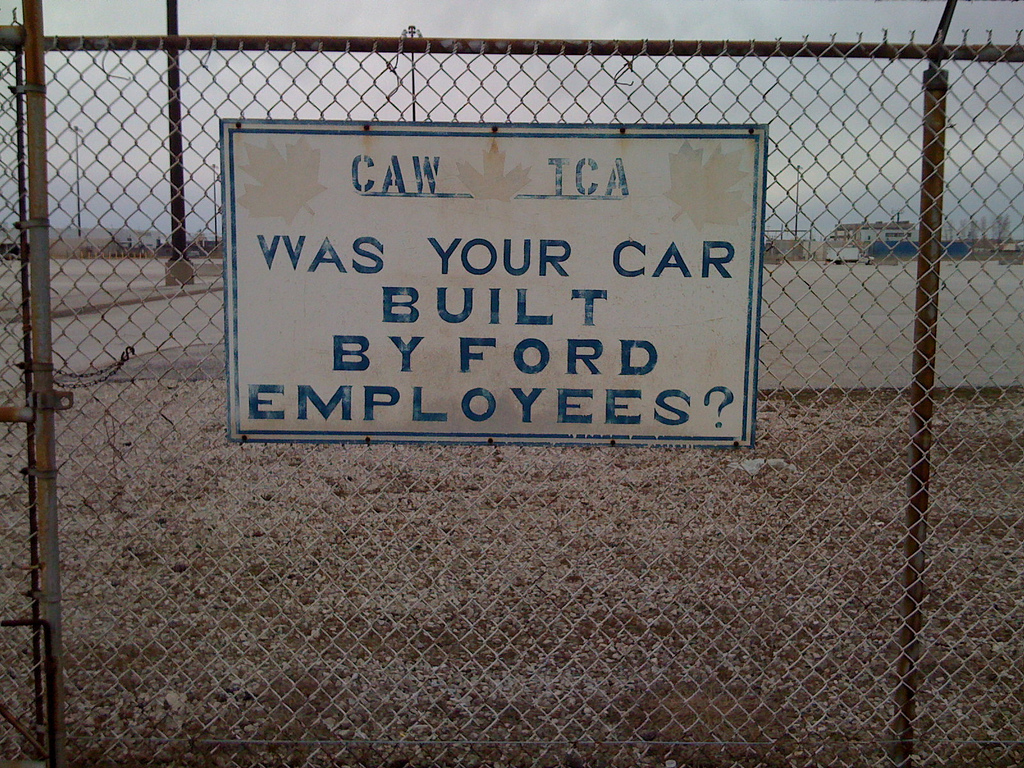

Photo: Shawn Micallef