The Harper government is targeting charities working on energy and pipeline issues, development and human rights and those charities with significant funding by labour unions.

A lot of coverage about this bullying and many of the stories — which picked up on the findings of my recent Master’s thesis — have portrayed these charities as the victims of the government’s rhetoric, which conflates charities with criminal and terrorist organizations, and of the government’s corrupt use of Canada Revenue Agency to fight its policy battles through politicized audits.

Why? Well, it was found that the rhetoric and auditing of perfectly legal “political activities” affects the ability of charities to pursue their goals by muffling and distracting from their work.

These charities are altering their communication through changes in content, tone, communication channel and frequency and making changes to their internal processes to reflect new policies introduced by the Harper government since 2012. They’re also preparing for and going through time-consuming audits of their political activities.

It is easy to portray these charities as victims because the Harper government’s actions reach beyond Canadian political norms, treating certain charities as enemies of the state rather than as groups of citizens with different policy preferences to those of the government.

But that’s not the whole story.

Most charity leaders interviewed for my study are aware that the government has no monopoly on power. They see their own power as publicly recognized experts in the issues related to their mission — whether it be climate change, international development, human rights, etc. The charities see they have power through the support of their members, donors and followers and through using their communication channels, and in their ability to affect public opinion regarding policy issues, such as the environmental risks of pipelines or the need for new policies to reduce childhood poverty.

The Harper government began its over-the-top anti-charity rhetoric and actions with a focus on environmental groups in 2012 because it was losing a public-opinion battle with environmental groups concerning climate change, expansion of the tar sands, building of pipelines and export of bitumen.

In their kick-off actions, led by then-Natural Resource Minister Joe Oliver’s “open letter” published in The Globe and Mail, cabinet ministers directly attacked the messengers rather than debating the messages. Charity leaders saw it as a desperate attempt to change the channel by smearing the charities’ reputations.

The Harper government’s framing of charities as ‘traitors undermining hard-working Canadian families’ was choice raw-meat to the hardcore party supporters, but the charities think it has backfired among average Canadians. Some charities even experienced short-term donation increases by playing on the “un-Canadian” riff in fundraising campaigns.

Sure, the Harper government’s abuse of power is affecting the performance of some charities. But the focus on damage to charities misses the bigger point: muffling and distracting these experts causes damage to society and democracy. We risk making poor national decisions if we’re not getting the full story at the very time Canada faces some of the toughest decisions in our history. Canada has never more needed deep and broad discussions of policy alternatives.

Charities themselves are responding just as Resource Mobilization Theory would predict of social movements: aware of their vulnerabilities to the threat of state authority in the form of CRA sanctions, most quickly responded to new annual reporting demands. They also changed internal processes around education, activity tracking, peer training and use of lawyers and accountants.

But they are also responding as would be predicted by Charles Tilly’s Social Movement Theory and Contention Theory. And some are refusing to be muffled, instead choosing “trench warfare” over public opinion as theorist Antonio Gramsci’s predicts for battles over fundamental values.

Recognizing their own power, charities increasingly collaborate with each other and discuss response strategies, such as the Canadian Council for International Cooperation’s decision last week to ask for a meeting with CRA. And, being shut out of directly contributing to public policy under this government, they build public opinion around their issues, such as the proposed tar sands pipelines, in order to indirectly pressure the cabinet.

Charities are building previously neglected links between different sectors, such as joining and working through the national charity umbrella and lobbying group, Imagine Canada. Some contribute to the Voices/Voix website that tracks the damage caused to national conversations through government actions against individuals, scientists, charities, non-profits and others. They’re also working to get charity-friendly, and pro-consultation policies into the 2015 election platforms of some federal parties, and discussing whether to launch a lawsuit against the federal government for abuse of authority.

Some non-profits (not charities) are knocking on voters’ doors in information campaigns targeting vulnerable federal B.C. ridings.

Within their own organizations, leaders and board members are weighing the advantages and disadvantages of adding non-profit arms that are not also charities. Working partly through a non-profit arm would enable them to participate in public conversations that are limited or forbidden to groups with charitable status, but requires costly duplication of administrative functions under law. And when some charities realized that they were significantly under the ten per cent of resources that may be devoted to political activities as defined by CRA regulations, their boards ordered them to increase that activity — not the outcome seemingly intended by the government.

Government has massive power that it can abusively use against citizen groups that it views as threats to its worldview. But citizens and their organizations need not submit. Charities have the power and the ability to resist and push back when they choose action over paralysis.

Gareth Kirkby is a recovering journalist and media manager who recently completed his Master’s thesis for Royal Roads University and works as a communication professional. Check out his blog at garethkirkby.ca and follow him on Twitter @garethkirkby.

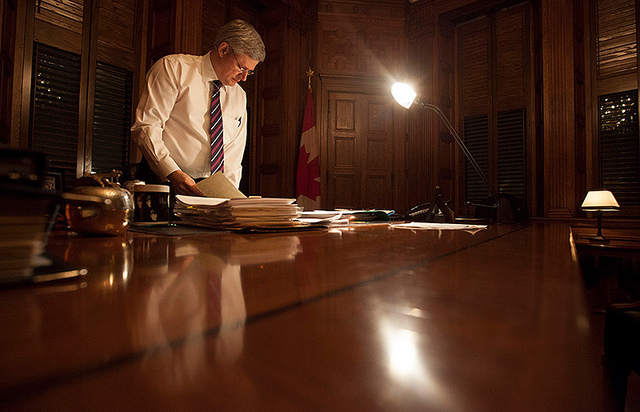

Photo: flickr/Stephen Harper