Marx and Engels famously wrote: “Workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.” They should have added: “And if you don’t pull together, a lot of you will die in bloody wars.” For if the workers of Britain and Germany and of all the other countries had heeded Marx and Engel’s call and refused to fight each other, then there could have been no war in 1914. But there was such a war because Marx and Engels failed to see, in the Great Powers game that was building up, that lethal popular nationalisms would erupt, that workers in each country would rally round their own flags, that nations would trump class, and that war would trump peace.

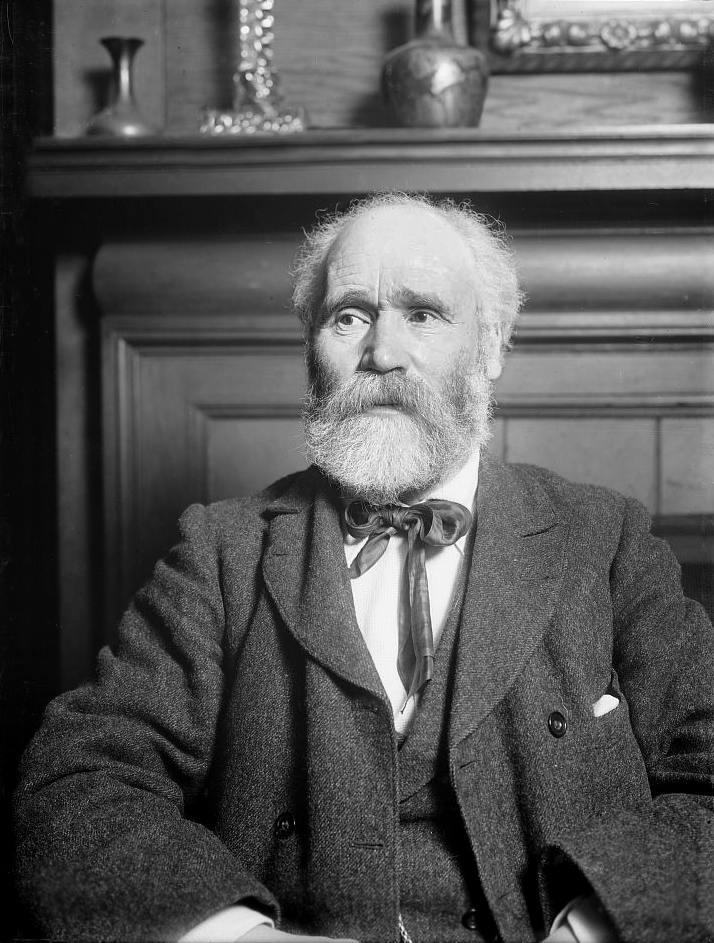

The American scholar Adam Hochschild tells the story of how this happened in Britain in his excellent, very readable, and very sad, book, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918 (2011). In his telling, perhaps the person who best exemplifies this failed hope is Keir Hardie, a name that deserves to be remembered for what he tried to do and still remains to be done. A child of the Scottish working class, he went into the mines at age eleven. He became a union man and a socialist. He was the first labouring man to be elected to the British Parliament. He was a founder of the Independent Labour Party in 1893 which became part if today’s Labour Party.

Hardie believed that socialism and pacifism were one and the same, that the socialist movement was a counterweight to war, that workers’ solidarity across borders was an expression of the universal desire for peace. He preached that in the event of war among the European powers, workers in all countries should call a general strike, refusing to go to war and refusing to work. Hochschild writes: “Hardie’s passion for justice knew no national boundaries.”

The outbreak of the war in 1914 betrayed all that Hardie stood for. Hochschild tells us that, as he spoke from the front benches of the House of Commons against the war, the backbenchers of his own party were softly singing the national anthem.

When war came, Hardie could not bear the thought of socialists killing each other. Old friends abandoned him. His spirit was broken. He suffered a stroke, recovered briefly, and died aged 59 in 1915, a year after the war began, in the midst of the insane savagery of gridlocked trench war on the Western front.

It’s the saddest of stories to read a century later. Hardie is history while Tony Blair, a more recent leader of the Labour Party who rushed to support the American War on Iraq, lives on, pronouncing on this and that while lining his own pockets.

The fate of French socialist leader Jean Jares was yet more awful. After the assassination in Sarajevo that set the events of 1914 in motion, he shuttled about Europe pleading for workers to strike rather than fight. His reward was to himself be assassinated in Paris by a young fanatic French nationalist who wanted war.

Germany had the largest socialist party in Europe and it was committed to peace. But when the critical vote came in the Reichstag, with crowds gathered outside clamouring for war, intimidated deputies gave their consent.

It seems that national publics wanted war when their elites put that option on the table. Meanwhile, democratic socialism was dealt a body blow from which, arguably, it has never recovered.

Moving up the class ladder, we have to ask: where were the Kings and Queens of Europe in the rush to the Great War? After all, so many were related to each other through intermarriage that the war, when it came, resembled a family feud desperately in need of a family therapist.

At the centre of the extended family was Britain’s Queen Victoria, who had reigned forever while her descendants set about the diverting business of producing offspring. She was herself the product of two German royal families. King George V of Great Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and the empress consort of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia — accounting for no less than three of the Great Powers — were all grandchildren of Victoria.

On learning of Austria’s attack on Serbia in response to the assassination in Sarejevo, Winston Churchill wrote his wife: “I wondered whether those stupid Kings and Emperors could not assemble together and revivify kingship by saving the nations from hell.”

All the costly pomp of monarchy would have been more that worth the price had it prevented war. It didn’t. Nationalisms trumped costly rituals and invented traditions.

As for the capitalists of each country, or each empire to be more accurate, there were learned writers who thought that the thickening entanglements among the Great Powers themselves through trade and investment in the decades prior to 1914 had created a new and potent interest in peace. That had not happened. The great surge of what is now called globalization utterly failed the most important of all tests.

Indeed, what may surprise when it comes to class, in Britain, officers, many from Oxford and Cambridge, died in greater proportion to their numbers than did soldiers. The ruling class sacrificed their children. The same was true in Germany.

Douglas Roche, Canada’s great peace activist, is now 85, and his hope only grows with his age. His inspiring new book, Peacemakers: How People Around the World are Building a World Free of War, reminds us that, in 1915, at the lowest point in one of the worst of wars, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was founded in The Hague. It is still functioning today. Marx and Engels might have been more successful if they had called for the women of the world to unite.

Image: Wikimedia Commons