I had long dreamt of this moment.

I realize that sounds horrid and morose, given how extreme the carnage was early Sunday morning in an Orlando nightclub where 50 people lost their lives after one person opened fire. But I have seen it, in my own imagination, over and over and over, with plenty of blood and lives lost in abject horror.

I think I first saw it when I would make the pilgrimage from Montreal to Toronto for the country’s largest Pride celebrations, in the 90s. There I would join thousands of others as we would march down the streets, eventually stopping to party enthusiastically in the streets, often kissing one another, sometimes removing much of our clothing, always celebrating the fact that, on this day at least, we had nothing to hide and everything to celebrate.

It’s not really like that on most days, when LGBT people have to watch what they say and how they act in public. I remember seeing Christian extremists protesting on the sidelines of the parade. “What’s stopping them?” I would ask myself.

The ties between the anti-gay religious right and the pro-gun lobby so often overlap, it seemed an inevitable marriage made in someone’s perverse sense of heaven.

It also arrived so vividly in my imagination because at that very time, many of my friends were dying or doing their best to survive the horrific disease we were all grappling to deal with called AIDS. That so many on the religious right were repeatedly referring to the disease as God’s wrath against gay men — in other words, a fate we deserved — only made the likelihood of a mass murder all the more probable.

A legacy of violence

In the late 80s and 90s, it often seemed some onlookers were taking a distinct pleasure in watching so many gay men get snuffed out. Larry Kramer came to refer to it as a holocaust; it was akin to what I call no-fault genocide. Homophobes didn’t even have to pick up a gun.

Perhaps it’s seeing so many movies, as doing so can open up your imagination of disaster. But it also seems so obvious: in a culture that’s as steeped in homophobia as our own, why wouldn’t something like this happen? Guns are available, LGBT people meet in public spaces, and the recent advances in legal rights often mean a backlash.

It happened to women famously in Montreal with the Polytéchnique massacre of 1989. There’s a long history of it happening to African Americans, most recently last year, when Dylann Roof opened fire inside a predominantly African-American church in South Carolina, killing nine. For whatever reason, people feel threatened when people who have been shut out of power ask to have some. It sounds like a simple equation, but it’s the ugly truth.

I think one of the bits of information I found most devastating, as I partook in the cable-news-feed ritual that follows a shooting like this, is the story behind the name of the Pulse nightclub where the massacre took place. One of the club’s founders, Barbara Poma, revealed that she had named the club in honour of her late brother, who had died of AIDS in 1991. It further connected the line of violence, hatred and apathy in the face of the death of LGBT people.

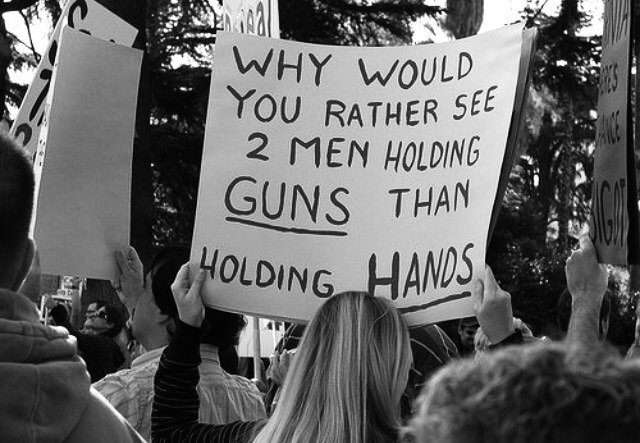

And then, the theory of the father of Omar Mateen, the American-born man who is now widely believed to be the person who took all of those 50 lives on Sunday morning, was revealed: Mateen had been horrified and disgusted by the image of two men kissing one another. He had complained angrily about having to be subjected to such an image, and went on about it for quite some time, his father recalled. This, the father said, is the reason he believed his son had opened fire in a crowded queer nightclub.

As Sunday dragged on, the inevitable statements of politicians piled up. And those statements began to become somewhat divided: American Democrats and Canadian Liberals and NDP politicians named the LGBT communities, while often discussing the need for more gun control; GOP and Conservatives were more likely to call for prayer and to evoke the need to fight terrorism.

Many on the right now find themselves in a very tricky situation: clearly an extreme mass shooting like this needs to be condemned immediately. But Mateen didn’t act in a cultural vacuum: on some level, he must have taken at least some of his cues in a country where there are now widespread debates over which washrooms trans people can use — and this despite the fact this issue has not been a problem, has never been reported to police as a problem, and in fact has been identified simply as a way to create a problem.

Religious freedom bills have been popping up in many states in the U.S., some of them passing into law. And in Canada, only just last month did the Conservative Party vote to leave behind their long-standing fight against the legal recognition of same-sex marriages. And that only came after a lengthy, bitter debate.

Not responsible, but maybe complicit

I realize many of you are now quivering with rage about the connections I’m making. Being a small-c conservative (or even a big C one) in a country like Canada does not make someone a rabid killer of 50 people. You’re right — it doesn’t. And I don’t hold you responsible for what happened in Orlando over the weekend, not for a moment.

But I ask you to take a few moments to think about your own attitudes and opinions, and the impact they do have. Do you really find the idea of two people of the same sex getting married makes you uncomfortable? Would the sight of two men kissing one another make you feel queasy? Would you cover your son or daughter’s eyes from such a sight? Would you really feel uncomfortable going to a bathroom next to a person who is trans? Do you still feel that LGBT people shouldn’t have equal access to the very institutions that allow people to pursue full, happy lives?

Because for many decades, many of us have been doing our best to educate our fellow citizens about what it means to be queer, about what our goals, aspirations and values are. We’ve been doing so in protests in the streets, university and college classrooms, newspapers and magazines, political campaigns, films, TV shows, books and online social media.

In the process, LGBT people have revealed ourselves to be every bit as diverse as the dominant straight population is and in doing so have won over much greater acceptance. In some instances, gay people have proven to be every bit as conservative as their straight counterparts, with equally conservative aspirations and life goals (I confess I have about as much interest in getting married as I do in joining the military — but that’s another column).

So if you still do harbor these nagging, uncomfortable questions about the identities and lives of LGBT citizens, I would ask you to take this rather extreme emotional moment to ask yourself one simple question: Why?

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Twitter/@MarcJacobs