Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

Earlier this week, from Goose Bay to Yellowknife, thousands of Nehiyaw, Dene, Metis peoples (joined by Canadians supportive of them) gathered in front of provincial legislatures, constituency and Aboriginal Affairs offices. They sang honour songs, danced jigs, and waved their flags and homemade protest signs out in the cold and the wind.

This hashtag movement known to some as #IdleNoMore (#NativeWinter to others) is challenging manifold issues in the Indigenous-Canadian relationship. Among the more critical:

-the move to strip environmental protections from most of this country’s waterways

-a lack of consultation on amendments to the Indian Act

-the chronic failure to maintain and uphold treaties

-the continued refusal to acknowledge the rights of those still without treaties

-repeated calls for a national inquiry on missing and murdered Aboriginal women

We’ve protested before; in fact, we do it often. At the very earliest origins of Canada as a country, Mississauga leaders (concerned by continued European encroachment) diplomatically expressed their frustration this way:

“You came as a wind blown across the Great Lake. We received you, we planted you, we nursed you. We protected you till you became a mighty tree that spread throughout our Hunting Land. With its branches you now lash us.”

When diplomacy failed, protest gave way to active, physical resistance throughout the late 1800s by Metis and Cree peoples on the Plains, the Tsilhqot’in and others in B.C., and the aforementioned Anishinaabe in Ontario.

With incidents of violence followed by more heavy-handed government suppression, appeals were made directly to individual Canadians. In 1923, Cayuga leader Deskaheh would complain:

“We are tired of calling on the governments of pale-faced peoples in America and in Europe. We have tried that and found it was no use. They deal only in fine words — we want something more than that. We want justice from now on.”

The pan-Indian political organization The League of Indians was formed soon after, sharing some of the same goals as Deskaheh. The Canadian government responded by banning the League: in fact, the time would soon come when all such Indigenous organizing would be prohibited under the Indian Act.

Eventually, returning World War II vets and victims/survivors of residential schools did get organized. They forced changes to both the school system and the Indian Act throughout the 1950s in what was becoming the so-called ‘Red Power’ movement. Their efforts culminated in a powerful response to the White Paper in 1969-70. And yet it wasn’t enough to prevent ongoing dispossession. Once again, Indigenous forms of protest evolved into more provocative confrontations, at places like Gustafsen Lake, Oka, Ipperwash and highways and rail lines during the 2007 National Day of Action.

The efficacy of these movements should not be discounted. They are directly responsible for the fact that our peoples still have some semblance of culture and lands remaining today, as well as legal rights (however limited). Still, those earlier movements also failed in many ways. Ultimately, we’ve been largely unsuccessful at wholesale, widespread change. This outcome is partially a consequence of the effective suppression by AANDC, obfuscation by the mainstream media, and appropriation of these movements by do-nothing leaders.

But I think the most significant factor, especially in more contemporary efforts, is our reactive posture, leaving us always on the defensive. When Canada introduces policy, legislation, or funding changes, we respond with outrage that the mediocre status quo might be upset. In the best-case scenario, the offending legislation is shelved.

The danger of this reactive activism is that it can actually serve to solidify some of the institutions we’ve come to accept, despite the fact that it is those very institutions that make up a large part of the problem. For instance, while rallying against the First Nations Transparency Act or the potential First Nation Land Ownership Act is important, it also means defending the existing Band Council system and/or land tenure arrangements on reserve — even though we know that both are extremely problematic and require fundamental change. But instead of working out the shape of that change, we inadvertently entrench an inherently flawed system. So as we move one step forward, we also effectively take one step back, mistaking inertia for movement. Such unwitting, stubborn idleness allows Canada to push its agenda.

So this new and compelling movement presents a unique opportunity. Firstly, it allows us to build on the momentum already created in creative and committed ways to continue raising our collective consciousness (the hunger strike by Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence as an active example). Secondly, it offers the chance to channel energy into considering alternatives.

Speaking recently with Anishinaabekwe writer Leanne Simpson about where we go from here, she advocates that we bring together Anishinaabe academics, activists, community members, leaders, etc. to talk about what we want and how we’ll achieve it. Generally, this means spending genuine time together to foster national movements and re-assert a real concrete plan, not just repeat rhetoric.

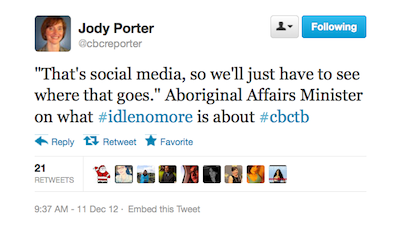

When the League of Indians, Deskaheh and Great War veterans started causing trouble in the early decades of the 20th century, Indian Agents responded by calling it “annoying” and “advising Indians to have nothing to do with it.” When the current Aboriginal Administrator John Duncan was asked about Idle No More, his curt response — “That’s social media, so we’ll just have to see where that goes” — echoed the same dismissive and arrogant tone of his predecessors.

Canada expects (and hopes) this movement will melt away. Making it sustainable and meaningful requires reflecting on past and current trends in activism among Mushkegowuk, Algonquin and Lakota peoples. That means honoring and being thankful for them, but also absorbing their lessons.

Hayden King is Anishinaabe from Beausoleil First Nation on Gchimnissing in Huronia, Ontario. Hayden is a writer, student, teacher and researcher based out of the Politics Department at Ryerson University in Toronto, Ontario.

Photo: Blaire Russell Photography.

This article was first published in Media Indigena and is reprinted here with permission.