Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

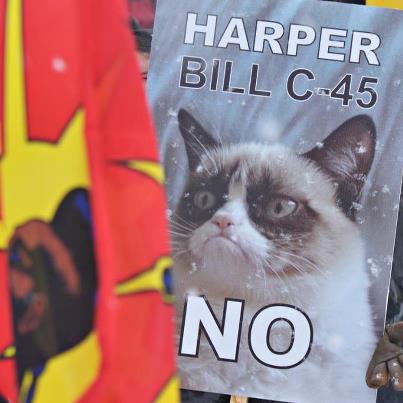

As Parliament resumes, Stephen Harper has made it clear that he remains committed to implementing Bill C-45 in the face of widespread social protest. But thanks, in part, to Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike, Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples are now working together, through the Idle No More movement, to grow a strong oppositional alliance against the Harper government, and Bill C-45 has become something of a lightning rod for criticism.

Yet, there is still much confusion about why Bill C-45 is so problematic. To help clarify the case against Bill C-45, this article first breaks down the Conservative Party’s rationalization of Bill C-45 and then examines how the bill can be understood as a dangerous attack on democracy and a continuation of the Canadian state’s support for colonial and capitalist expansion and exploitation.

The mainstream media has worked hard to convince the public that Idle No More is an over-reaction by “special interest” groups to the perfectly reasonable omnibus Bill C-45, known formally as the Jobs and Growth Act, 2012. For example, Tom Flanagan — University of Calgary political scientist, Indigenous “expert,” Fraser Institute pundit, close advisor to Harper until 2004 — recently took to the Globe and Mail to defend the bill and explain to Canadians why they should support the legislation as well (see Tobold Rollo’s critique of the “Calgary School” of which Flanagan is most certainly a major player).

Flanagan uses the rhetoric of neoliberalism to justify the bill. In fact, he summarizes his main point in the title of the article: ‘Bill C-45 simply makes it easier for first nations to lease land.’ He claims that many communities have raised their standard of living by leasing parts of their reserves for commercial development including for “shopping centres, industrial parks, residential developments, casinos and anything else that might make money. Such projects create jobs and generate property tax revenues that first nations need to provide better services for their members.”

However, Flanagan asserts that because of stipulations in the Indian Act relating to the leasing of reserve lands — namely that such decisions must be agreed to by a majority of the community by referendum, at a meeting in which a majority of the community is present, or, if quorum is not reached, through the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs — such commercial deals are being slowed unnecessarily. Flanagan contends that “First Nations pursing economic development have complained for years that the slowness of these procedures caused extra expense and sometimes even the loss of lucrative projects to competing jurisdictions able to move more quickly.”

As a result, Flanagan argues that the Conservatives really passed Bill C-45 to help Indigenous peoples. While Bill C-45 makes extensive amendments to over 60 laws, he focuses on two crucial changes to the Indian Act: “(1) replacing approval by order-in-council by approval of the Minster of Aboriginal Affairs; and (2) replacing the requirements for a majority of a majority to simply majority rule.” He then rationalizes such tweaks thusly: “These amendments do not force first nations to do anything. They only make it easier for those who want to lease land to do so.” He does not, of course, explain how these changes effectively make it more difficult for those in Indigenous communities to oppose leasing treaty lands for capitalist development and to protect the lands and waters of traditional territories, which is a major concern of Idle No More.

Thus, in examining Bill C-45 we must keep firmly in mind political economy’s central guiding question: who benefits the most? From this perspective, Flanagan’s assertions — and the Conservative Party’s explanation of Bill C-45 in general — must be challenged on a number of fronts.

First, the changes sharply narrow the scope of democracy in Indigenous communities by removing a broad-based collective power and replacing it with the kind of majority rules mentality that can, for example, see a prime minister elected to a majority government with only 39 per cent of a popular vote in an election in which only slightly more than half of all “qualified” Canadians voted, as happened in the federal election of 2011. In fact, only 5 million out of Canada’s population of 33 million elected the Harper government. Such a decision-making system allows small groups in society to grasp power and wield it as if they have carte blanche — the Conservatives’ recent omnibus bills, of which Bill C-45 is but one, are an example of this in action.

Second, Bill C-45 was simply imposed without any consultation with Indigenous peoples themselves; it was a unilateral political change to treaty rights that violates previous contracts, and as such is simply unacceptable and, it could be argued, illegitimate. Nevertheless, Flanagan justifies the lack of meaningful discussion and dialogue with Indigenous peoples: “Consultation has become a shibboleth of our time. It is, indeed, an essential part of democracy, but it can also become a constraint on freedom.” Translation: if we ask the people what they want they might disagree with our plans for capitalist expansion and then we won’t be free to do whatever we want. This is not real democracy in action.

Third, Bill C-45 will, more correctly, increase the “freedom” of those pursing capitalist accumulation by removing democratic checks and balances in Indigenous decision-making. There can be no doubt that “freedom” has become the go-to watchword for today’s capitalist class and those who work on its behalf.

In essence, Bill C-45 will make it easier for particular groups in Indigenous communities, with corporate support of course, to push through controversial development plans that will, undoubtedly, benefit community members unequally. Thus, the consequences of Bill C-45 might be understood as yet another form of what geographer David Harvey has called “accumulation by dispossession,” that is the privatization of public lands or resources designated for common use to be used, instead, to generate profit for a small minority.

Instead of mobilizing a rough community consensus, which would require cooperation and compromise, smaller factions can now convince a majority of a minority of peoples present at a meeting to vote in favour of, say, allowing resource extraction to take place on protected lands or pipeline projects to be built over traditional territories. In short, the Conservative government, with its obvious ties to Alberta’s tar sands and resource development, does not want Indigenous communities to be able to block pipeline development or other resource extraction deals, as was the case in the 1970s with the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline project.

Bill C-45 must be understood as a direct attack on democracy in Indigenous communities and a deliberate attempt to open up Indigenous lands to capitalist development; the bill is about removing the barriers and obstacles to the “freedom” of capitalist accumulation. And as Alanis Obomsawin’s new film People of the Kattawapiskak River has pointed out, leasing Indigenous territories for capitalist accumulation is certainly not a panacea for Indigenous peoples’ problems. Indeed, Obamsawin shows how the Attawapiskat First Nations’ signing of an agreement allowing the De Beers company to operate the Victor Diamond Mine on traditional territory has not eliminated the sordid conditions for many in the community but has in fact exacerbated inequality, an inequality that people like Chief Spence are trying to draw much-needed attention to through their actions and support of the Idle No More movement.

Now that Chief Spence has ended her hunger strike those involved at the grassroots of Idle No More are faced with the task of developing new strategies to grow the movement. Despite Harper’s insistence that Bill C-45 is here to stay, refocusing oppositional energy around the consequences of Bill C-45 and its connections to colonial and capitalist oppression could serve to bring different movements together to defend Indigenous sovereignty and treaty rights in particular and to oppose neoliberalism more generally.

Indeed, if securing increased “freedom” for capitalist accumulation is a central pillar of Bill C-45 then opposing it and other capitalist attacks (e.g. undercutting the power of public and private sector unions, changing EI provisions, underfunding health care, limiting refugee rights and protection, privatizing lands and resources etc.) must become a focal point of our struggles and, most importantly, guide our tactics and strategies in more radical directions moving forward.

Sean Carleton is a PhD Candidate in the Frost Centre for Canadian and Indigenous Studies at Trent University. He is currently a visiting student at the London School of Economics and Political Science in London, UK.