Please help rabble.ca stop Harper’s democratic demolition. Become a monthly supporter.

As summer finally gets underway after a record-breaking winter, farms and orchards across Canada are preparing to open their gates to hungry locals eager for a taste of the season’s first fresh produce.

With anticipation running high, it’s easy to forget that so much of our “local” food is planted, nurtured and harvested by “foreign” migrant farmworkers of colour.

In 2012, there were more than 6,000 migrant farmworkers in British Columbia alone, a fraction of the almost 40,000 employed across the country. Most come from Mexico and Jamaica through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), the principal agricultural stream of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP).

On June 20, the federal government announced several sweeping changes to the TFWP. These include a replacement of the previous Labour Market Opinion with the new Labour Market Impact Assessment, a spike in request fees from $275 to $1000 per foreign worker and a reduction in the length of “low-skilled” worker contracts from two years to one.

These so-called “reforms” were met with immediate criticism from migrant justice groups from coast to coast to coast and are likely to result in the premature deportation of thousands of migrants across the country.

Chris Ramsaroop is an organizer with Justicia for Migrant Workers, a grassroots migrant advocacy group operating in Ontario and British Columbia. He fears that with the reduction of worker contract and visa lengths, “This could be the largest mass deportation in Canadian history.” But he adds, “This isn’t a done deal. We still have the ability to take steps to resist this via both legal and community-based strategies.”

Even with these changes to the TFWP, it’s essentially business-as-usual for Canadian employers hiring migrant farmworkers. While the retaining of farmworkers’ jobs comes as a relief, the government’s continued silence with regard to migrant farmworkers is troubling. The lack of attention, positive or negative, paid to TFWs in the agricultural sector reflects not only our general ignorance of the SAWP, but also the federal government’s implicit belief that this stream of the program is actually working without issue. But we know differently.

Migrant farmworkers who come to Canada under the SAWP constitute a bonded or unfree labour force. Their work contracts and, by extension, their right to remain in Canada, are tied to single employer. They do not choose where they work, cannot easily change jobs and cannot freely search for other employment. They do not choose where or with whom they live and bunk, and their housing is frequently isolated, racially segregated and maintained at a standard unacceptable to most Canadians. Complaints about their living or working conditions are often met with immediate dismissal and deportation, causing many to put up with workplace abuse, including racist verbal and sexual assault, as well as unsanitary, even dangerous, housing arrangements.

In addition, most migrant farmworkers have dependents including spouses and young children who are neither permitted to accompany nor to visit their family at work in Canada. These migrant men and women, as well as the families they leave behind, must cope daily with the heartache caused by long term separation from their families — a separation lasting up to eight months each year, in some cases for decades.

Adding insult to injury, and in direct contestation of Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Chris Alexander’s claim that many farmworkers acquire residency in Canada, there is no path to permanent residency for migrant farmworkers in the SAWP.

Even B.C.’s provincial nominee program, designed for individuals with “experience and qualifications needed by B.C. employers,” does not facilitate the permanent residency of farmworkers or their families.

Indeed, migrant farmworkers can labour their entire lives in Canada, picking the fresh, local and organic food Canadians demand, without ever stepping out from under the discriminatory and repressive labelling given to so-called “temporary” “foreign” workers, let alone escaping their legal subjugation.

The discursive and material divide between “foreign” and “local” workers is significant here.

“Canada, as a nation, has been built on a foundation of expulsion and exclusion of Others,” says Ramsaroop. “We have constructed ourselves as a nation through the creation of programs such as the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, which is legally constructed to deny rights and entitlements that permanent residents enjoy.”

Significantly, he adds, “It’s not a coincidence that the same communities that endured colonialism, slavery, indentureship and the Bracero program are today living and working under these contemporary forms of indentureship. The federal government and employer organizations’ defense of a labour migration program that denies humanity to racialized migrant workers is based on reaffirming Canada as a white settler nation.”

The SAWP represents the most precarious and least regulated of the TFWP streams, yet it is continually overlooked by the media, neglected by the government and ignored in popular discussions of migrant worker abuse. The well-being of those individuals and their families who make it possible to put fresh food on our dinner tables seems to be, itself, permanently off the discussion table.

With all of this in mind, and as many of us prepare for yet another season of delicious, locally grown produce, we can’t help but ask: what about migrant farmworkers?

Elise Hahn is an organizer with Radical Action with Migrants in Agriculture. She is also a Master’s candidate at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus and studies immigration, labour and race.

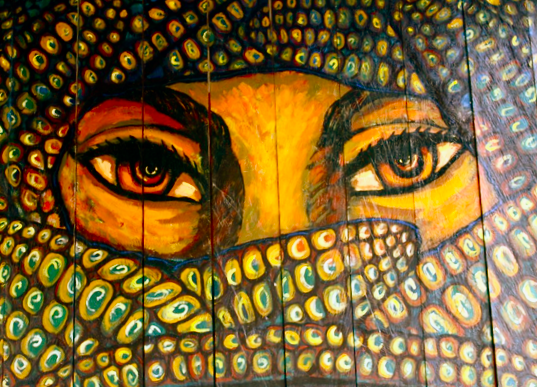

Photo “Mural in the Zapatista caracol of Oventic: Rebellion and Resistance for Humanity, Chiapas, Mexico. by Levi Gahman