Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

“Canadians are social democrats, but most don’t support the NDP,” said pollster Marc Zwelling at an NDP renewal conference in 2001 — the last time the party found itself in similarly dire straits. After a decade of Liberal austerity measures in the 1990s, he said, polls showed that voters prefer balanced budgets, but not at the cost of compromising the welfare state. Voters don’t die on this hill — the NDP shouldn’t either.

Fourteen years later, falling commodity prices wreaked economic havoc and Harper delayed his pre-election federal budget in spring 2015. Trudeau and his top strategist Gerald Butts made no secret of their intentions to swing left.

Journalists clearly saw Butts’ signature on the 2015 federal campaign. “The careful development and rollout of flashy, progressive policy, the polished delivery of it on the campaign trail, the all-important wedge issue to try to isolate the NDP: Gerald Butts’s fingerprints on the McGuinty campaigns in 2003 and 2007 are as evident on the deficit-spending Trudeau campaign of 2015.”

On May 4, Trudeau made a pre-campaign announcement that he would increase income taxes on the top 1% to reduce them for the “middle class.” (See part one of this series.) Once the official campaign began, the Liberals geared up for their second policy aimed squarely at outflanking NDP to the left: deficit spending to stimulate a shrinking economy.

Trudeau’s economic advisors had been planning an infrastructure program for at least a year, geared largely toward winning back progressive urban voters in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. “Within our means there are decisions that can be made around the kinds of investments that actually give us returns, whether it’s in education or infrastructure like public transit, without having to fall into deficit,” Trudeau had said back in January.

By the summer, it made Keynesian sense to use infrastructure spending to get out of Harper’s recession — even if that meant running deficits. In the first leaders debate on August 6, Mulcair forced Harper to admit that the Canadian economy had shrunk consecutively for five months — only one month from a technical recession. But it was the Liberals who adapted their infrastructure plans to position themselves as the anti-Harper party, taking full advantage of the contracting economy.

The NDP walked into the line of fire aimed at the Conservatives even before the Liberals even had a chance to launch their deficit-funded infrastructure program. On August 25, Tom Mulcair announced that the NDP would balance the budget regardless of the recession. The Liberals couldn’t believe their luck. A Liberal insider told the Toronto Star, “I don’t get it….They had a foot on our throat and they took it off.”

Trudeau lumped Mulcair in with Harper on economics the same day: “Let me tell you this, the choice in this election is clear. It’s between jobs and growth or austerity and cuts — and Tom Mulcair just made the wrong choice.” Political commentators familiar with Butts recognized the strategy. “This can only be one thing — a gambit to shore up the Liberals’ left flank and make a direct play for Liberal-NDP switch voters.”

But with the NDP pulling ahead of the pack to 40 per cent in the latest poll — the highest level of support they would receive during the campaign — Mulcair said the NDP is “not entertaining any thought of running a deficit, even if global economic trends continue to worsen.”

The very next day Butts and Trudeau drove the wedge in further. The Liberals officially announced that they would run $10 billion deficits for each of the next three years. They would increase annual infrastructure spending up from $6.5 billion to about $12.5 billion to get out of Harper’s recession.

As widely expected, later that week on September 1, Canada entered an official recession. A technical recession provided the perfect rationale to jettison a balanced budget policy proving more unpopular every day. Tim Harper at the Toronto Star warned: “Mulcair risks his own core support by trying to out-balance Harper even as polling data confirms that a deficit aimed at creating jobs and building infrastructure would be tolerated by a majority of Canadians.”

Polling numbers from early September showed strengthening of support for deficits to promote growth. “Most voters — 58 per cent — are alright with modest deficit spending,” Kyle Duggan wrote in iPolitics, “suggesting the campaign debate on deficits may help the Liberals to poach NDP supporters and red Tories based on Justin Trudeau’s promise to focus on economic growth rather than balancing the budget.”

Nevertheless, Mulcair held the line that he could get out of the recession (and pay for $15 child care) with a modest corporate tax increase. Over the next few days, the NDP lead evaporated, falling into a statistical tie with the other two major parties.

By October a full 78 per cent of Canadians surveyed supported deficits for infrastructure to stimulate the economy in a recession.

Why didn’t the NDP adapt?

“Tommy Douglas is the model that I want to follow. Seventeen balanced budgets,” said Mulcair, executing the longstanding NDP strategy to push back against Conservative attacks on NDP economic management. His campaign relied heavily on the economic records of provincial NDP governments. Of course, the NDP could have looked to more recent precedents than Tommy Douglas. Earlier this year the Alberta NDP’s Rachel Notley swept to power by opposing Jim Prentice’s widely loathed austerity budget.

The NDP campaign was in a bind. From the start of Mulcair’s NDP leadership run, he promoted himself as the candidate opposed to saddling future generations with social, economic, and environmental debts — a conviction he emphasized in his one-on-one interview with Peter Mansbridge. Then Mulcair called Trudeau a flip-flopper in the leaders debate on the economy, increasing the political cost of any on-the-fly policy changes.

While Mulcair admitted that stimulus spending was necessary in 2008 — the worst financial crisis since 1929 — the campaign had to agree with Harper that the recession of 2015 was different. “We can’t run a deficit. We’re the NDP,” insisted a senior advisor in late September. The campaign rejected deficit spending as a flexible tool of governing.

Mulcair’s anti-deficit stance seemed like a confident shift to the centre that would scoop soft Liberal votes. But unlike a classic wedge issue, which unites your own party but divides your opponents, the NDP’s shift to the centre exposed its left flank and failed to attract Liberal supporters. It smelled opportunistic in an election about authentic change.

The repeated failures of tacking to the centre raise a perennial existential question about the NDP. Why shift away from core NDP principles and policies when they are so popular? Support for progressive values remains high across Canada.

Zwelling’s advice to the 2001 NDP renewal conference is as pertinent today: “The federal NDP is not in trouble because voters have turned conservative or because social democratic values are out of style. The polls put the blame for the party’s demise squarely where it belongs: on the NDP. Its candidates have failed to harvest their potential vote.”

As the NDP enters a new era of renewal, it’s time to return to the fundamental question: how to translate support for progressive policies into votes, rather than tacking ever closer to the centre. Cleaning house of top party strategists and the leader — as necessary as such moves may be — may not be enough.

The deficit debate didn’t propel the Liberals into first place, but it put Trudeau in the game as the anti-Harper on economics.

The Liberals learned their lesson from the Bill C-51 backlash: this was a “change” election and you win by looking like the polar opposite of the incumbent.

This was part one of a three-part series: “How the Liberals outflanked the NDP on the left.”

Read part one: Tax the rich: How the Liberals outflanked the NDP

Read part three: The NDP’s queasy opposition on the niqab

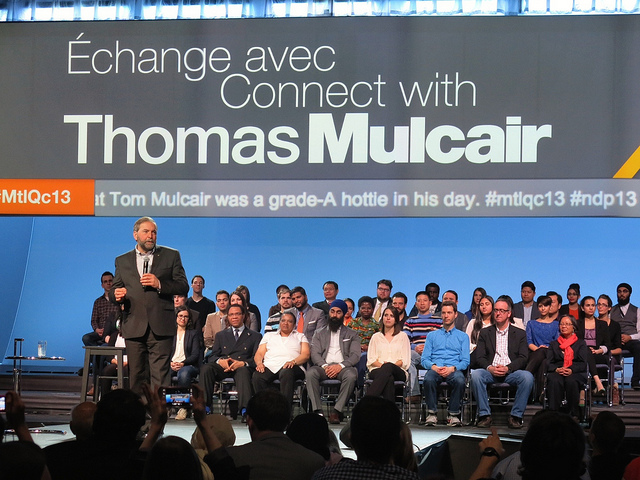

Photo: Kim Elliott

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.