In part 1 of Karl Nerenberg’s look back to 1968, there were assassinations, massacres, protests and a near-revolution in France. In part 2, we will look at the early Pierre Trudeau era and the beginnings of an Indigenous peoples’ movement in Canada.

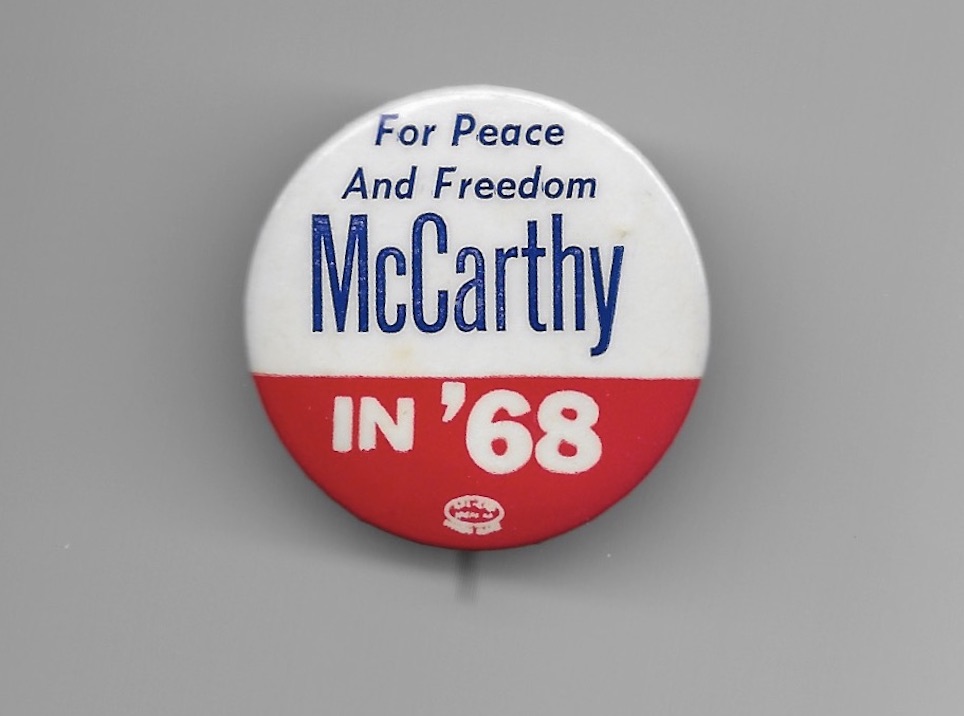

In 1968, young Americans went clean for Gene — Eugene McCarthy that is — the scholarly senator from Minnesota, who, on an anti-war platform, challenged a sitting president for the Democratic Party nomination. That president was Lyndon Johnson and after McCarthy came a surprisingly close second in the New Hampshire primary, Johnson announced he would not seek another term.

The more radical youth, who marched, and sometimes fought, in the streets, thought the ballot box a waste of time. They scoffed at the clean-for-Gene crowd. And the revolution-focused radicals differed from the change-the-system-from-within folks culturally as well. Political protest songs did not turn them on. Radicals preferred the Stax and Motown sound to acoustic folk. They related to Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man” and Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street” more than Phil Ochs’ “Draft Dodger Rag” or Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

As for Lyndon Johnson, a president who was chased from office by his own party, his reputation has improved over time.

Johnson had the blood of tens of thousands on his hands. Nonetheless, he is now seen as much as the author of such major social initiatives as Medicare (health care for the elderly) and Medicaid (health care for the poor) and the voting rights and civil right acts, as of the lunatic and brutal mission in Vietnam.

Today, Republicans actively seek to roll back just about everything progressive Johnson achieved. And Johnson’s stature has grown when viewed against the motives and characters of those who would undo his legacy.

The Vietnam War was continued after the U.S. suffered major defeats

It was early in 1968 when the National Liberation Front of Vietnam (a.k.a. the Viet Cong) launched the so-called Tet Offensive, which had a devastating impact on the American and South Vietnamese military. Reasonable people would have seen the writing on the wall and sued for peace there and then. Instead, the Americans, first under Johnson, but mostly under his successor Richard Nixon, expanded the war to neighbouring Cambodia and Laos, to disastrous effect. In the end, nothing worked militarily or politically and the Americans had no choice but to withdraw. Ironically, today, the U.S. is best friends with the notionally communist party government of a united Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands died needlessly in a callous exercise of Western ego and hubris.

While all of this was happening in the headlines of the West, in West Africa, far from the Western media’s glare, hundreds of thousands were dying in the Nigerian Civil War, the so-called Biafran War, which had started a year earlier.

In Nigeria, the battle lines and alliances were bizarre. Circumstances and self-interest made for strange bedfellows. The federal Nigerians had the full and unqualified support of their former colonial overlords, the British, and of the Soviets. Both had an interest in maintaining access to Nigeria’s rich reserves of oil and gas, most of which is found in the breakaway eastern Biafra region.

The French had similar reasons — access to oil and gas — for supporting the secessionist Biafrans. The Portuguese also supported Biafra, but less for its natural resources and more for geopolitical reasons. Portugal was still under the rule of the proto-fascist Salazar, and had persisted in maintaining its African colonies long after Britain and France had granted theirs at least nominal independence. The Portuguese hoped to win at least the passive support of one Black African country for their retrograde colonial project by helping the Nigerian breakaway region.

Was it time for a French-speaking leader?

In Canada in 1968, the governing Liberals had to choose a new leader and new prime minister. There was a notional, but entirely unofficial, Liberal rule, going back to Laurier, that the party should alternate English and French leaders. One would have thought, in that light, that there would be more than one French-speaking candidate to succeed Lester Pearson. It did not turn out that way.

Early on, many Liberals approached former union leader and senior Pearson cabinet minister Jean Marchand urging him to run. He demurred, saying he did not speak English well enough. That was not really true. Marchand probably had other, very personal, reasons to stay out of the race.

Marchand’s colleague Pierre Trudeau had limited political experience and was seen by many as something of a dilettante. He had, to his credit, impressed during his brief tenure as Lester Pearson’s justice minister, and, to some backroom Liberal operators, he looked just like the candidate who could embody the spirit of the age: youthful, insouciant, athletic, articulate and sexy without being too Rock-Hudson-style handsome.

The doubts persisted, however, and many Liberals wanted a more traditional candidate — alternation be damned. At the April 1968 convention, Trudeau only barely won over a large field on the fourth ballot.

Much has been written and said about Trudeau’s great and lasting influence on Canada. He did have his accomplishments, notably the repatriated Constitution and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In many respects, however, Pearson accomplished more in five years than did Trudeau in more than 14. Canadian-style health care and the Canada pension plan, both transformational social policy milestones, were both Pearson achievements, for instance.

To be fair to Trudeau, Pearson’s success was, in considerable measure, as much a product of the times as of the leader.

In the early 1960s, much of the West had embraced activist government — government that would expand the welfare state, impose high taxes on the rich and take steps to at least ameliorate chronic poverty. Any mainstream Canadian prime minister would have been inevitably swept up in that spirit of social democratic interventionism. In fact, one of the most revered Pearson-era accomplishments, universal, public, comprehensive health insurance, got its start in a royal commission headed by Justice Emmett Hall, who was appointed by Pearson’s Progressive Conservative predecessor John Diefenbaker.

It was in many ways a backward time

When we look back to 1968, it might be useful to remember what did not exist back then, as much as what changes were taking place.

- Abortion on demand was still a crime.

- Maternity leave was virtually non-existent, and in many workplaces, open and acknowledged discrimination against women was commonplace.

- The death penalty was still on the books, although it had not been used in six years.

- Indigenous residential schools were going strong, as was the Sixties Scoop.

- Running water in Indigenous communities was an extreme rarity, and those communities were governed — as arbitrary, petty dictatorships — by the neo-colonial agents of the white government.

Indigenous Canadians, or at least those known as status Indians, had only recently gotten the vote, and the landmark court decisions upholding Aboriginal and treaty rights — Malouf (James Bay Quebec), Calder (Nisga’a, British Columbia), Morrow (Northwest Territories), Delgamukw (B.C. Interior) — were all in the future.

None of the candidates for the Liberal leadership in 1968 uttered a single word about Indigenous people. Indigenous people were entirely out of sight and out of mind.

There were glimmers of change on the horizon.

The Pearson and then Trudeau governments had their eyes on the oil and gas and other resources of Canada, north of the 60th parallel. In reaction, Indigenous communities started to organize.

In 1968, for example, the Yukon Indian Brotherhood was born. Indigenous groups, for the first time started to make common cause with often better financed and resourced environmental organizations based in big cities. It was the beginning of an alliance that continues to force business and government to take notice — witness the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion.

In 1968, gender politics, in Canada, in the U.S. and elsewhere, were also undergoing a transformation. The world, or, at least, much of it, was witnessing second wave feminism.

The media tended to reduce the movement to images of bra burners. But feminism’s second wave produced results as earth shaking as those of the suffragettes more than half a century earlier.

Those who remember back alley abortions, women who got pregnant losing their jobs, less pay not only for work of equal value but for exactly the same job done by men, and the routine dismissal of sexual violence as the fault of the victims, will know what feminism’s second wave, which might have reached its apogee in 1968, achieved.

Parliamentary reporter Karl Nerenberg opens 2018 with a special historical series, which looks forward to the coming year in politics by looking back. In this collection of articles, we travel back through 50 years of history, one decade at a time. Read the full series, spanning 1968-2018, here.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.