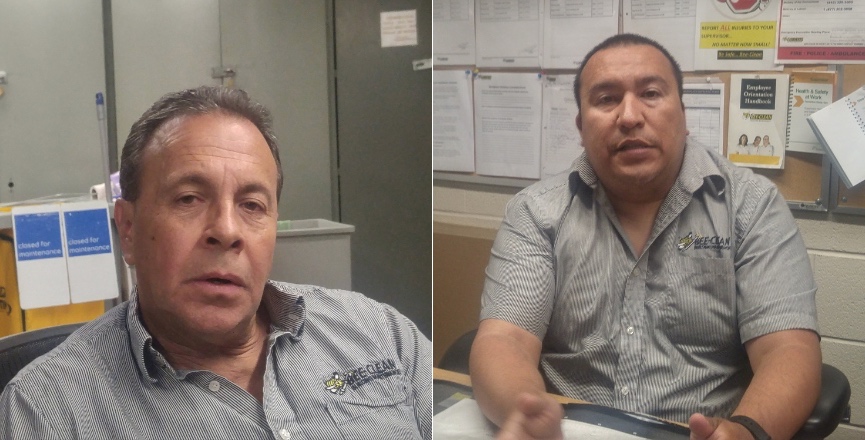

Martin Echevarrieta finishes his eight-and-a-half-hour janitorial shift around 4 p.m. at a residential building in Toronto’s North York area.

The 39-year-old is in charge of cleaning 22 floors, and takes pride in standing up to the rigours of the job. When initially recommended for the position two years ago, he was told that the employer wanted someone responsible who could handle the workload.

“I said, ‘Why not?’ Plus they give me good benefits plus a little more money [than my previous job]. But it’s what I like. I like to work,” he says, in his customary soft-spoken manner.

The management trusts him now, he says, crediting his strong work ethic. One day, he hopes to be promoted to superintendent.

After about a minute’s drive, Echevarrieta unites daily with his old friend, Enrique Turnainsky, 63. The older of the two Hispanic men also finishes his cleaning shift around the same time.

But they’re not headed home, or meeting for an after-work drink at a bar or café.

From 5:30 until 11:30 p.m., they lead the janitorial staff at a commercial building for a major telecommunications firm, where they have been employed for over a decade.

As the white collar workforce begins to empty out of the office tower, the two men start their second job of the day.

Reversing a pattern of disrespect

Turnainsky and Echevarrieta were part of the group who unionized in 2011, motivated by a toxic workplace atmosphere. Their organizing drive was part of the Service Employees International Union’s (SEIU) cross-border Justice for Janitors campaign that has made gains for over 225,000 custodial staff in dozens of North American cities including Los Angeles, Vancouver and Toronto.

As a union steward for SEIU Local 2, Turnainsky is the liaison between the management and workers. He is the point man for grievances, safety issues and any major problems that might arise at work.

Echevarrieta is the lead hand, a cleaner who coordinates with the building management on day-to-day tasks for the janitorial staff.

“The conditions at the workplace were stressful,” says Turnainsky, recalling the period before unionization. “It was kind of abusive.”

“Let’s say if the workers didn’t complete the job at the end of the shift, or if the workers didn’t do a proper job, it was constant menace — [the management would say], ‘I want to fire you.’ And they fired people, straight away,” Turnainsky says.

Workers faced harassment in the form of insults, and from supervisors who often lurked and hovered, alongside a myriad of other issues such as staff being prevented from going on planned vacations at the last minute.

After unionization, the routine confrontations gradually gave way to a more congenial workplace, where the janitors asserted their rights, thanks to the language enshrined in their contract.

“It took time to change the mentality, for them to follow the rules,” Echevarrieta says.

Management reps were forced to adjust, but as a union steward, Turnainsky too had a learning curve.

Over time he educated himself on labour laws, the Ontario Labour Relations Board’s procedures and the provisions of the collective agreement.

“We started to know how to use the rights that we had through the union, and balance it with the obligation that we had to the company, right? This is so important,” Turnainsky says.

The two have formed a workplace environment they are clearly proud of — a cordial relationship between the workers and the employer, grounded in respect and relatively fair working conditions.

An industry-wide problem

The harassment of custodial workers is rampant in the industry, according to Jorge Villa, an organizer with SEIU Local 2.

Villa’s insights are based on five years of experience dealing with the problems of custodial workers in Ottawa and Toronto. The union represents close to 6,500 janitors across the two cities.

He says management’s prerogative is to get the job done, and they will hire supervisors who can be enforcers in the workplace. In that sense, unfriendliness can be an asset for prospective middle-managers.

“The supervisors only care about getting the work done. So if that means yelling at somebody, or being a little mean to them, or doing anything to get them to hurry up, that’s all the supervisor really cares about. And that’s all the company cares about,” Villa says.

“As long as work’s getting done, it does not matter if the worker’s going through hell every day, you know. If they are losing their mental health by being in this workplace, it doesn’t matter at all.”

The largely racialized, female and immigrant workforce can make for easy prey. Villa says that newcomers in particular can be targeted because they may not necessarily be informed about their own rights.

While having a union helps, it doesn’t provide blanket protection. Villa says he often has to guide workers on documenting abuse, in order to file official complaints.

He finds that when workers take a stand and file formal complaints, management often backs down. However, for workers in precarious situations who are desperate for work, and relatively new to Canada, challenging authority at the workplace isn’t simple — especially when employers use a range of range of divisive, anti-union tactics.

Among the management’s bag of tricks is to hire supervisors who can favour workers from their own racial group, in order to disenfranchise other workers.

“If there’s a group of Filipino and Spanish speaking workers in the building, they might try to get a Spanish-speaking supervisor to split the workplace,” Villa says.

The role of the union’s workplace leaders becomes imperative then, in maintaining a sense of cohesion and unity, which can be a powerful force to overcome.

“When it works, it really works. It’s a great sight to see the diversity and everyone working together to lift everyone up,” Villa says.

Solidifying their gains

Over the years, aside from providing a channel for amicably resolving workplace conflicts, the union has brought in better health and safety standards at Turnainsky and Echevarrieta’s office building.

Workers have guidelines in respect to using cleaning chemicals and detergents, their application, the use of gloves, safety equipment and so on.

“Back then, they were using the vacuum maybe with the wire cut,” Turnainsky says. “Right now [they can’t do that], we have a committee.”

“If you don’t have a union, some companies don’t care about [health and safety],” he says.

Turnainsky and Echevarrieta illustrate a transition whereby workers have gone from being disposable to having their humanity respected.

“Sometimes people do disgusting stuff in the bathroom,” says Echevarrieta. “Before you had to clean it. Now you have a choice. You can say, ‘I’m not comfortable.'”

If they find themselves in such a predicament, janitors have access to a protective suit and a mask. Or if there is a stain that is too high on the wall, they have the right to get a ladder and be accompanied by a colleague to ensure their safety.

Working hard — and struggling

Even as Turnainsky and Echevarrieta can celebrate the evolution of their workplace environment, low wages continue to be a persistent problem across the industry. Janitors represented by SEIU typically make between $14.95 to $16 an hour, with some reaching a high of $17.75 at the end of the latest three-year contract in 2022.

Inadequate pay is the reason for their 16-hour work days. Neither of them complain much, accepting their grueling schedules as normal in the exploitative system of low-wage work for racialized immigrants.

Turnainsky was studying to become a lawyer in Uruguay before political turmoil forced him to emigrate in 1989. Custodial work was his source of survival.

Echevarrieta arrived from Argentina in 2005 to follow in his father’s footsteps, who worked as a janitor besides briefly operating a trucking business in Canada.

For someone who began working at age 11, Echevarrieta is accustomed to a life of hardship.

“Every day that I wake up, life is a struggle,” he says matter-of-factly, when asked about his work schedule.

“[It’s a] surprise for my co-workers to see me in the morning so happy. I have problems too. I leave my problems in the car or my house,” he says. “But I try and make it better for me. And I like what I do.”

Enjoying work is a theme that comes up in conversation with the duo every so often.

Echevarrieta takes pride in his obligation to work, and keeping his employers happy.

“I don’t say, ‘Oh no, it’s not my job, this is not my responsibility.’ When you [want] something [to be done], we have to respond.”

At both jobs, his managers also entrust him with responsibilities, which grants him autonomy and a measure of respect.

That empowerment allows him to push back on behalf of his team, when the demands of management are overwhelming.

Much as it’s understandable that in some ways the job works for Turnainsky and Echevarrieta, surely there is something wrong with a system that necessitates people working 70-hour weeks to provide a decent standard of living for their families?

Turnainsky agrees.

“That is a part of the societal problem — the organization of the country,” he says.

“If you [and your wife] want to work only eight hours here in Canada right now — probably your life will be just from the work to your place. Pay the rent, pay expenses a little bit, but probably you are not allowed to go on vacation, to enjoy your life because why? Because here, it is too expensive.”

“If you have children or you want to help children with university or college, you have to do what Martin [Echevarrieta] and myself are doing,” says Turnainsky, who helped pay for his daughter’s education at Toronto’s Ryerson University.

The spiralling costs of living essentially require people in the low-wage sector to work themselves to exhaustion and forgo time with their families, if they are to have any hope of upward mobility.

The same old fears

Over the years, SEIU has substantially improved working conditions for its members in Ontario — including several victories on the bargaining table such as health benefits, personal days and a recently won pension plan.

However, inadequate wages continue to profoundly impact the lives of janitors, and others in low-wage jobs. As a recent Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives study showed, minimum wage workers cannot even afford to rent a modest one-bedroom apartment in major Canadian cities.

The ability of unions to fight for fairer wages is, however, constrained by larger systemic forces.

Janitorial work is handled by cleaning companies that bid for contracts for government-owned and commercial buildings. Contracts are awarded to the lowest bidders, who minimize costs through low wages and understaffing.

“When the contractor wins the bid, 99 per cent of times they’ve outbid the existing contractor [through underbidding] to make more money,” says Luis Aguiar, an associate professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia, who has extensively researched janitorial work.

“One of the key features of [contracting out] is to make a profit on the back of workers, and especially those most vulnerable,” he says.

In a particularly blatant recent example, a new contractor at a downtown Toronto condo attempted to drastically reduce the benefits and compensation package of five Filipino cleaners, ultimately locking them out of their jobs for months.

The conception of the work as “dirty” and low-value, and the largely new-immigrant, racialized and female workforce, helps normalize the societal discourse of the “unskilled” workers who must “work their way up” to achieve a better standard of living.

This narrative works particularly well if it can be internalized by immigrants themselves.

“When I come to Canada, my father sit with me and he said to me, ‘Martin. This is not your country. You have to respect this country. This is like we are born again,'” Echevarrieta says.

The undervaluing of their labour, and the invisibility that has become intrinsically tied to custodial workers — due to the interplay of gender, race and immigrant status as well as the predominance of night-time work — helps perpetuate systemic discrimination.

And then, despite the many successes of Justice for Janitors, the jobs themselves are intrinsically precarious. Since cleaning jobs at offices are predominantly done after regular business hours, most of SEIU’s members work part time and require other sources of income.

To be sure, workers like Turnainsky and Echevarrieta have made their jobs work for them, through the support of their union. Due to their sacrifices, their children can live a better life.

But there is a vulnerability to low earnings that is not lost on those who have traditionally been consigned to the margins of society.

In regard to implementing discipline among his three children — doing chores, being financially prudent — Echevarrieta says that his wife jokes that he is a dictator at home.

“I say, ‘You don’t know what’s gonna happen. In the years coming, maybe it’s gonna be hard.’ You never know, they need to be prepared.”

Next week: Part 2 of rabble’s series: “The Daily Grind of Working as a Janitor.”

Zaid Noorsumar is rabble’s labour beat reporter for 2019, and is a journalist who has previously contributed to CBC, The Canadian Press, the Toronto Star and Rankandfile.ca. To contact Zaid with story leads, email zaid[at]rabble.ca.

Image: Zaid Noorsumar