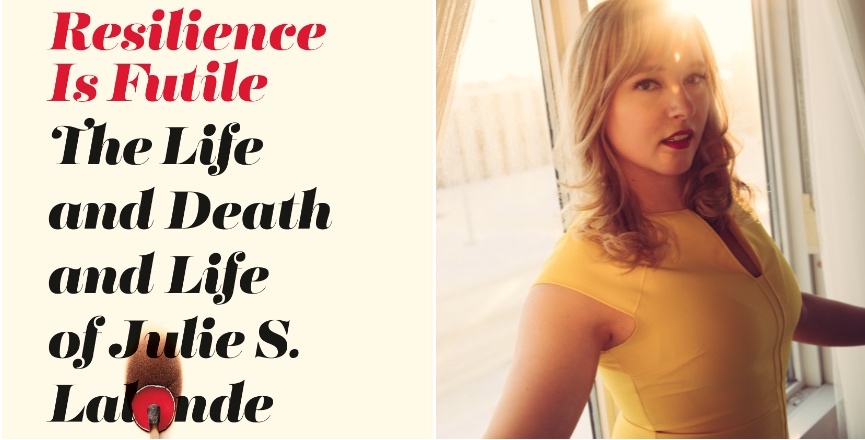

Julie Lalonde’s memoir, Resilience is Futile: The Life and Death and Life of Julie Lalonde, visually demands your attention, from the flame on the cover, to the letters from her stalker ex-boyfriend incorporated within the design. With such a unique and powerful hard copy that told the emotional story of Lalonde’s personal life and activism, her newly released audiobook posed some challenges. While many authors do not narrate their own audiobooks, Lalonde tells me she became empowered to be the voice of her own story after her friends told her they could not imagine it any other way.

She describes the difficulty of reading aloud letters, notes, and poems in her stalker’s handwriting. Not only did she have to describe the documents, she had to read them into a microphone, alone in a recording booth. She had not read the letters since she first received them. Lalonde tells me she was encouraged to overcome the pain of reliving those movements by those wanting to see their stories of survival reflected.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

rabble: Why was it important for you to tell your story not only as a personal narrative, but to weave in political and systemic criticisms?

Julie Lalonde: I started to write a book when a fancy agent approached me. It is commonly known that mainstream publishers did not want to tell my story with political analysis, instead they were looking for trauma porn. There seemed to be no interest in survival’s healing or in scathing commentary on the systems that uphold this violence. But for me there was no question about it: I wouldn’t tell my story without investigation of the broader pieces like the complexity of resilience, our culture’s individualization of domestic abuse situations, and problematizing the treatment of some survivors as beacons of hope. That is why I was so happy to find Between the Lines as my publisher, who explained they are interested in my book precisely for the feminist analysis. I felt it in my bones; I didn’t want to dig up my nasty personal trauma without serving a purpose. My book is meant to be messy; it is not linear just like healing.

r: As you wrote in your essay for Sick of the System: Why the COVID-19 Recovery Must Be Revolutionary, the lockdown measures that followed the global COVID-19 pandemic have posed new barriers to those seeking help, especially to those trying to leave domestic abuse situations and abusive partners. What are your predictions on how this has and will continue to impact survivors?

JL: When the lockdown started, I put myself in my own shoes 15 years ago. I would have been stuck in a house with my stalker, legally mandated to stay indoors. If you are being stalked during the lockdown, you cannot evade your stalker; stalkers have heightened capacity to find you in person and online, since you are most likely in our own home the majority of the day. Women who are trying to leave an abusive person might not even know the logistics and legalities of moving during this time. People are asking: how can I even move? Can I look for a new apartment?

While services like shelters and sexual assault centres are considered essential and always remained open, there is misinformation and that meant people did not and do not take advantage of these services. Many therapists moved online, but can you really talk freely while your partner or family members are in the same or adjacent room?

It seems like there is no good time to speak about violence against women. There is no political clout for caring about women. When it comes time to find room in the budget, poverty, women, and racial justice issues, are the first to be trimmed. While I think many of these barriers existed before, the pandemic and lockdown shed light on their severity.

r: Black Lives Matter protests have recently been gaining momentum in Toronto and many parts of the United States. What is the interrelation of racial justice movements with your own work?

JL: I worry about the momentum of all progressive political movements and the bandwidth of the leaders. When I saw the BLM protests erupt all over the United States after the death of George Floyd, it brought me back to our work around the Ghomeshi case. The #MeToo movement drained a lot of activists but it created concrete change that will be hard to take away. Before that moment, rape culture was brushed off as nonsense. Now it is common vocabulary and used in mainstream media reporting. BLM is doing the same thing; they are fighting and gaining big wins that cannot be discounted. One simple example is seeing an outlet like the Ottawa Citizen using and explaining the phrase: defund the police.

It is our job as activists to make sure we transform the anger people have into action. I remember how pissed people were during the Ghomeshi case, but five or six months later their eyes were glossed over. That is our failure as progressives and as leaders of movements. We need to give people the tools to tear down the house.

Barâa Arar holds a bachelor of humanities from Carleton University and is currently an MA candidate at the University of Toronto, focusing her research on photography, gender and colonial resistance. Her writing has appeared in This Magazine, CBC, and the Globe and Mail.