I have had the privilege of being able to champion the cause of human rights on the pages of this fine magazine—and, god knows, there are plenty of violations of rights to talk about in the 21st century!

In my own work on behalf of victims, I have focussed particularly on rights violations among powerless children who suffered early institutional trauma which has had lasting, life-long effects, leaving their nightmarish imprint on both bodies and souls.

Now elderly, these childhood victims of perverted provincial authority and power from so many decades ago, still walk among us daily, still carrying their pain and grief like a silent disease, condemned by their original oppressors in church and state to be treated like lepers, untouchables, undeserving of justice or reparation for their mistreatment.

In a flagrant abuse of their civil powers, these authorities were guilty of criminal mistreatment of innocent children, condemning them, not to sad death, but to tragic life.

Which is why I now want to propose that these living stricken deserve a public memorial as much as dead heroes deserve a cenotaph. We must find public ways to express our sympathy, share their grief, encourage reflection, in order to recognise and memorialise their plight. Let us strive to honor Pope Francis’s ultimate challenge to victimisation made in Quebec City in July 2022 —“NEVER AGAIN!”

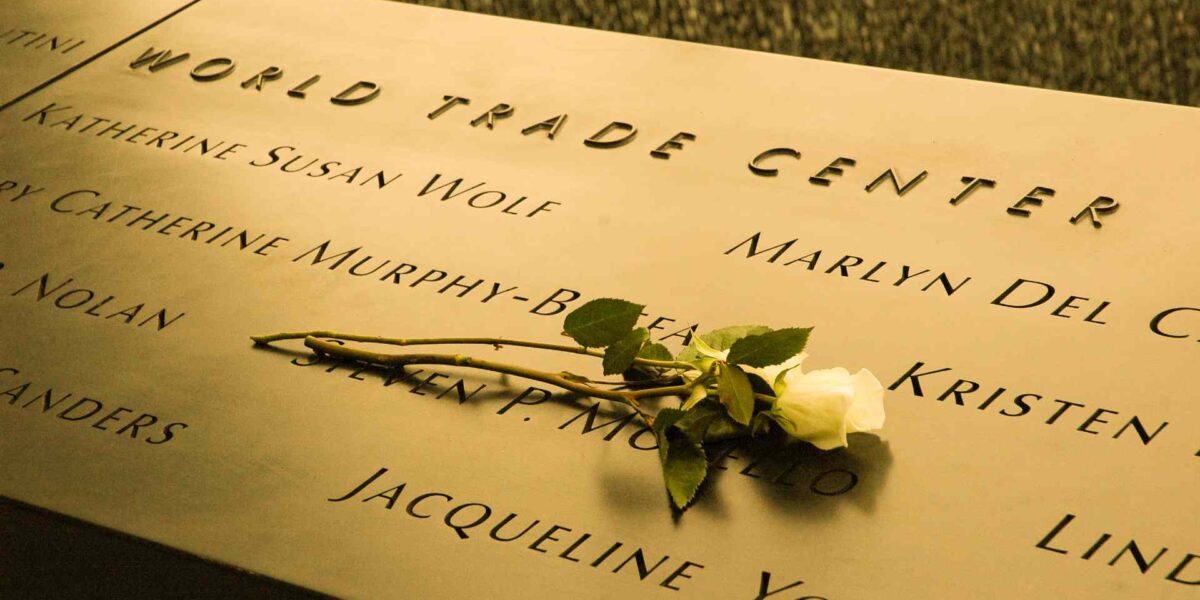

Where can we find inspiration for our resolve to remember the living as well as the dead? When I wrote about this historical, social, cultural obligation last June, I invoked the 9/11 annual memorials as a paradigm, not only for remembrance, but also for national solidarity. I felt that the event, and the courageous reactions to it, could help us remember all victims, everywhere, who share our common humanity. In that spirit of bearing witness, my exhortation “Lest we forget” was offered as a rallying cry.

My inspiration then was a sister (Anthoula Katsimatides) who had lost her brother John at 9/11, yet urged us to “take the torch and pass it on”, for the future good of mankind. And at this year’s 9/11 Memorial (dare I say “festival of life”?) in New York City, we were again exhorted to bear witness to collective tragedy as our obligation, not just to victims and survivors, but also to future generations.

This time the message was delivered by Jay Winuk who lost his brother, Glenn, in the attacks. Effectively carrying Anthoula’s torch, Jay participated in a volunteer initiative called “9/11 Day” which “… aimed to transform Sept. 11 from a day of tragedy to one of service.”

As reported by the New York Times, Jay’s brother “Glenn Winuk was a volunteer firefighter who was at home getting ready for work at Holland & Knight, the law firm where he was a partner, when he saw the first plane hit the North Tower on television. He ran to the scene and died trying to help evacuate his firm’s offices in the South Tower”……. “For me, personally, it’s cathartic.” Jay Winuk, 65, said of the service day he helped create. “It’s a great tradition to hand off to the next generation, which is so important to us, because 100 million people in this country weren’t even born when 9/11 happened.”

Survivors of tragedy like Anthoula and Jay teach us how to create new birth after death so that society’s loss will not have been in vain. 9/11 is a universal teachable moment that the past should inspire the future, that tragedy can be redeemable via right acts.

In this new vision of past, present, and future, the living and the dead gain reciprocal privileges: our elderly Canadian survivors become new foster brothers to bereaved 65-year-old Jay Winuk in New York, while his narrative, in turn, offers them a pathway to guide them in their quest for a healing catharsis of justice and reconciliation.

And that is the memorial lesson I want us to learn here. Just as we formally memorialise the victims of fatal tragedy, like Glenn and John, let us also cherish the memory of the living survivors of human tragedy, like our elderly Canadians abandoned by their oppressors. They too need to know that we, their fellow citizens, have not abandoned them, that they can still enjoy expectations of recognition, of support for their rights—to know, regardless, that “je me souviens”— we remember!