Each year, we here at rabble ask our readers: “What are the organizations that inspire you? Who are the activists leading progressive change? Who are the rabble rousers to watch?” And every year, your responses introduce us to a new group of inspiring change-makers. This is our ‘rabble rousers to watch’ series. Over the next few months, we’ll be sharing features about the people and organizations you nominated. Follow our rabble rousers to watch here.

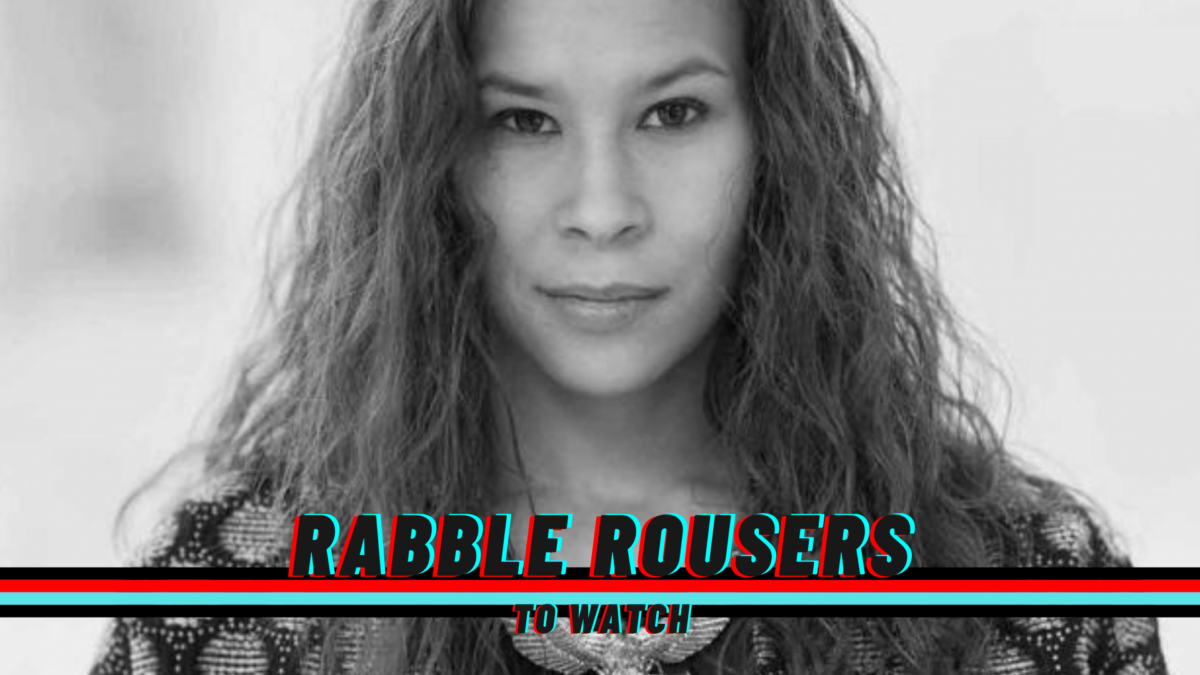

Our November rabble rouser to watch is poet and activist El Jones.

Based in Halifax, N.S., Jones is a powerhouse in social movements focused on anti-racism, human rights, and decarceration.

In September 2020, she was appointed chair of a 15-person subcommittee which was tasked with defining “Defund the Police” in Halifax. Jones and the subcommittee compiled a 218-page report which featured 36 recommendations to reallocate resources away from the police to more appropriate service providers.

Jones is an outspoken activist and dedicated member of her community who we’re proud to highlight as this month’s rabble rouser to watch. In her interview for rabble, she outlines what motivates her about the work she does and how anybody can participate in activism.

El Jones on her activism:

rabble.ca: Can you tell me a bit about the kind of activist work you do?

El Jones: Yeah, so I do a lot of activism really focused on fighting state violence. A lot of work with people in prison, organizing with people in prison, obviously fighting for prison rights. Then a lot of connected work with people facing deportation or immigration detention. I also do a lot of work with women experiencing violence. So women in prison shelters – policing, of course. So really trying to work in those places, where people mostly feel the sharp end of the state. Also, of course, trying to organize across different movements. So that touches on environmental justice, it touches on labor, it touches on all the different issues that we’re fighting and trying to build more of those solidarities.

rabble.ca: Can you tell us about how much time this type of activism/work takes?

EJ: I think when you’re doing this kind of work, there can’t be a schedule, right? Especially for example, with prison, people get out and they call and they call. So [sometimes] you’ll have a barrage of calls [at] like 7 p.m. is when everybody’s getting out. And then you might spend two hours on the phone for the rest of the evening or three hours, just call after call. But you know, you might be in the middle of a run and somebody calls. And that’s the time they have, 20 minutes. So it can be quite relentless.

And then when you’re in the middle of a campaign. So for example, if you’re familiar with the case of Abdoul Abdi, which was a deportation that we were fighting of a Somali child who had been in foster care and then was being deported. That was 24 hours, I mean, we would be on the phone until 3 a.m., get up, go to work, you know, 6 a.m., get off work, get back on the phone.

So it can be quite a bit of work, obviously, especially in the thick of things and very unpredictable. Often, [you] have to drop what you’re doing, commit to that, and then come back to whatever else you’re working on. It can also go quite long, as well as quite intense.

rabble.ca: And so how has having to commit that type of time affected you?

EJ: I always say that I think it’s a blessing to be asked to do this work. You know, when people trust you enough to turn to you, I think that is an honour. So I would never complain about that.

But obviously you’re a human being and it gets hard … I think it can get challenging if you don’t feel that you’re in a good place, and then [try] to give of yourself. That can be hard. But I think something that I really try to remember is that in any human rights case … there is somebody whose rights are being violated at the center of that.

And it’s not about you, it’s about them. And if they’ve managed to reach out to you, it’s life or death, really for them … So I think I just really try to hold that in mind. And remember, it’s not about me.

And many benefits have come to me from doing this work. I’m the one that gets into the media, I’m the one that has a book … The person that’s sitting in a cell doesn’t have the opportunity to write a book. So to also remember my own power in that situation, and privileges, I have to do this work, because it is a privilege.

rabble.ca: So what keeps you motivated? Because it is very intense and involved.

EJ: I always say that, you know, it’s the people that you’re working with. There’s intense love. When I saw Abdoul for the first time after his deportation being stayed … He ran towards me, he picked me up and twirled me around. I felt so much joy. I never felt that much joy in my life. Because we had really struggled together. We’re still close, we don’t just finish working with somebody, and then you know, you’re kicked to the curb. Like we have a relationship, we have love, we’re in each other’s lives, we’re family with each other.

Then of course, the people that you’re around, I mean, Lynn Jones; I’m lucky to live in a community with just an amazing elder like Lynn who has taught me a lot of what I know about community organizing. Rocky Jones, who taught me a lot about what I know. So I’m very blessed to be in a community with the African Nova Scotian community with people who have been doing this work, and were doing it long before it was cool and trendy. Desmond [Cole], Robyn Maynard – we work together, we pick each other up. So there’s a lot of love in this work and a lot of shared work and a lot of people carrying the load together.

rabble.ca: How can we open up this work so that it’s more of a mass movement?

EJ: I always say that not everything everybody does is activism. But everybody can do activism. What I mean by that is that there are real strategies.

There’s been hundreds of years of black people, from the time of enslavement, talking about these issues. So we know what works, our elders have taught us: “this is how you go into the meeting, this is what they’ll do to you in the meeting, how to do a petition, how to organize long term.”

So often also, we think of mobilizing as activism. This is what Kwame Touré (formally Stokely Carmichael) was talking about, right, that mobilizing is like a protest. Organizing is the long-term work of getting your ducks in a row all the time. And that’s less glamorous. So people often don’t want to do that work. Everyone wants to come to the rally and be on camera. And it’s the stuff that you might be doing for five years before that, the slow organizing work, the most thankless work.

We [also] need to do a better job of mentoring young people, giving young people training, because so often people come in cold, don’t get a lot of support, end up having a bad experience … So I think we need to do a better job of passing down knowledge.

And I think also … there’s no transformative justice, there’s no abolition, without mutual aid.

Obviously, we have a big vision … but it’s not going to happen tomorrow. So we have to – on a daily basis – think about ‘what can I do today?’ … We have to … understand that on a day to day basis, we are taking small steps through organizing together. It’s not going to be in my lifetime, it’s not going to be in your lifetime. It’s not gonna be in our grandchildren’s lifetime, but we keep working and stepping towards it.

Note that this interview has been condensed for brevity; and the full interview with El Jones can be found here.