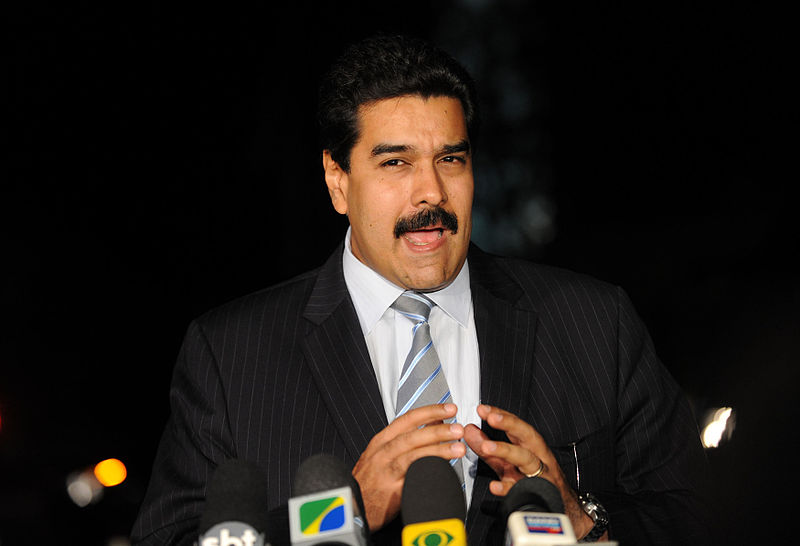

The first week of the new Parliament was quite predictable — until late Friday afternoon when, out of the blue, Global Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland announced sanctions on forty Venezuelans, including President Nicolas Maduro.

As the Global Affairs department explained the move, about two weeks ago Canada and the Trump government of the U.S. formed an “Association,” the aim of which was to “take economic measures against Venezuela and persons responsible for the current situation in Venezuela.” Canada is now following through on its pledge to the Trump administration. It has imposed sanctions similar to those the U.S. imposed a while ago.

Venezuela is an important target for Trump.

The U.S. President used part of his maiden address to the United Nations General Assembly to slam Venezuela’s elected socialist government, yoking it, in an act of monumental false equivalency, with the psychopathic regime of North Korea. Earlier, Trump had said the United States would not rule out a military option in dealing with Venezuela, evoking American gunboat diplomacy of the not-so-distant past.

Maduro and Chavez partly to blame for economic woes of Venezuela

Economically, Venezuela is in a severe crisis, suffering both runaway inflation and shortages of food and other necessities. Part of the cause of this crisis lies in the bad choices of the Maduro government, and even, to some extent, its predecessor, the Hugo Chavez government.

Gabriel Hetland, a sympathetic analyst, explained the complex causes of Venezuela’s crippled economy in The Nation, a little more than a year ago.

Put simply, Chavez turned the country into too much of a petro-state, financing generous social payments, and nationalizing firms to turn them over to their workers, with dollars from oil exports, which were abundant when prices were high. Chavez and Maduro also failed to invest sufficiently in the productive capacity of Venezuela’s national oil company, PDVSA.

The country became too dependent on exports of a single commodity that served to finance imports of many essential goods. When the price for that single commodity dropped, economic dislocation inevitably followed. Declining exports depressed imports, which fuelled inflation. These conditions fed off each other — exacerbated by corruption and a fixed currency — and engendered something resembling an economic death spiral.

The Maduro government claims the root cause of the crisis is that the United States and its business allies in Venezuela have been waging an economic war against the Chavista regime. Hetland disputes that claim, but only in part. While he insists the Venezuelan government must shoulder a good part of the blame, he adds “there is clear evidence that the economic war is real, and is one of the factors behind the current crisis.”

Hetland compares the current situation of Venezuela to Allende’s Chile in the 1970s, when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger aimed to “make the Chilean economy scream” to bring socialist president Salvador Allende down.

The Nation author identifies three facets to the “economic war.”

“The first,” he writes, “is hoarding of food and basic goods by private producers opposed to the government, to deliberately manufacture scarcities and generate popular opposition …”

The second is the disruption caused by U.S. sanctions. These punitive measures (which Canada has now joined) “send a message to would-be foreign investors that the country being targeted may not be a safe place to invest in.” This happens “at a time when Venezuela is in desperate need of dollars, but is prevented from gaining access to them …”

Hetland’s third facet is “the economic and psychological cost of the opposition’s often violent push for regime change.”

“In addition to the direct material costs of violent protests, which have targeted state-run health clinics and other public institutions and undoubtedly led to extensive property damage,” Hetland writes, “there are significant but harder-to-calculate psychological costs borne by the public.”

Feeling cornered, Maduro tries an end-run around the opposition

In Venezuela, the government has been unable or unwilling to tackle corruption and undertake certain necessary economic measures, such as floating the currency. The intransigent opposition has made matters much worse by refusing to even recognize the government’s legitimacy and by its willingness collaborate with outside forces seeking to overthrow the government. This standoff has not only aggravated the economic crisis; it has engendered a political crisis.

The Maduro government’s response has been to circle the wagons. It has attempted an end-run around the opposition-controlled parliament (the National Assembly) through the creation of a new elected body, a constituent assembly. There was an election this past summer for the constituent assembly, which is now stocked with Maduro loyalists. The opposition boycotted that election.

Although, in theory, the constituent assembly is designed as a constitution-drafting body, it also has the power to assume most of the elected parliament’s powers. It can even suspend the coming presidential election.

A number of countries and organizations see the creation of this new body as an effort to subvert the democratic and fair electoral process in Venezuela.

As might be expected, Canada, the U.S., the EU and conservative regimes in Latin America, including that of Brazil, all condemned the Maduro government. In the case of Brazil, the condemnation was a bit rich, given the illegitimate way the current Brazilian president seized power from the duly elected president, Dilma Rousseff.

But some less predictable folks have condemned the Maduro government as well, including Human Rights Watch and the Vatican.

In announcing Canadian sanctions on Friday, at the United Nations in New York, Freeland said: “We are horrified to see Venezuela slip into dictatorship.” The Global Affairs minister added, “Canada is a country that has a strong reputation in the world as a country that has very clear and cherished democratic values, as a country that stands up for human rights.”

Freeland did not explain why the (elected) Maduro government’s potential flouting of some democratic principles was worse than the anti-democratic actions of, say, the Saudi monarchy, which not only denies many basic rights to its own citizens, and beheads some of them in public for non-crimes such as witchcraft, but interferes with the rights and well-being of its neighbours, such as Yemenis. We Canadians have not only failed to impose any sanctions against non-democratic Saudi Arabia, we have sold it weapons of war.

Could the fact that Canadian sanctions against Maduro and his allies might make the U.S. president at least a little bit happy, at a time when we are re-negotiating NAFTA, have something to do with Canada’s haste to act in the case of Venezuela?

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.