I’ve dedicated a lot of time and energy to understanding and improving how we elect governments in Canada. Yet despite having had more access to Minister of Democratic Institutions Maryam Monsef than the average Canadian, I feel more confused than ever about what we are to expect from the electoral reform process.

Over three months ago I ventured out to the University of Toronto to attend a community consultation on electoral reform initiated by Minister Monsef. Based on the Government of Canada website, she set out to “raise awareness of electoral reform and provide an opportunity for [individuals] to engage in discussion with others about the future of Canada’s democracy.”

Similar to consultations in other cities, the time and location of the Toronto event was listed only two days in advance. It was held in the middle of the afternoon, on a weekday, in a physically inaccessible space. As I walked up the stairways and squeezed into a desk, I wondered exactly which Canadians Minister Monsef was expecting to hear from. Who else other than predominantly older, educated, middle or upper-class voters could be expected to show up to a last minute, mid-afternoon weekday consultation listed on a hard to find government web page?

As a deeply engaged twentysomething Black, Muslim woman, I’m accustomed to looking around these types of spaces and seeing almost no one that looks like me. But in a process that vowed to do better, this was exceptionally disappointing. During Minister Monsef’s opening remarks she thanked us for coming and jokingly addressed us as “democracy geeks.” While this is reflective of her personable engagement style, it also reveals the insider nature of this and other public consultation processes.

Although concerned, I was keen to participate and I asked the Minister, on that afternoon in mid-September, about the possibility of extending the consultations deadline to engage a strong diversity of Canadians. Instead of answering my question, Monsef posed one of her own, asking me if it was more important to delay or get rid of first-past-the-post?

Although she prefaced this by acknowledging she was learning a great deal about the barriers some faced in participating in these conversations, her response was wholly dissatisfying. It suggested that although the process was clearly flawed, moving quickly was more important than mindfully creating the conditions for the greatest number of people to participate in this important decision about our democracy.

Not long afterwards, I was pleased to receive an invitation from Huffington Post to sit down with the minister for a digital town hall to dig further into the conversation. Given that I was still deeply engaged in this issue and had been organizing town halls and canvassing with Leadnow, I was eager to revisit the subject of creating a more inclusive and accessible consultation process and electoral system.

I’d composed three questions, but there was only enough time for me to ask one of them: Beyond getting rid of first past the post what are the Liberals doing to make voting more inclusive and equitable — such as by making voting day a holiday or introducing online voting?

The minister didn’t directly answer my question or the host’s that evening. Instead, we heard many anecdotes and few answers that created more confusion than ever on where the Liberal Party stands with regards to its commitment to listen to the desires of Canadians on what electoral system is best.

When I asked the minister how the government will reduce barriers to voting, she acknowledged there are accessibility issues, but spent more time sharing accounts she heard at town halls about the difficulties of getting to the polling station than describing how these barriers will be addressed.

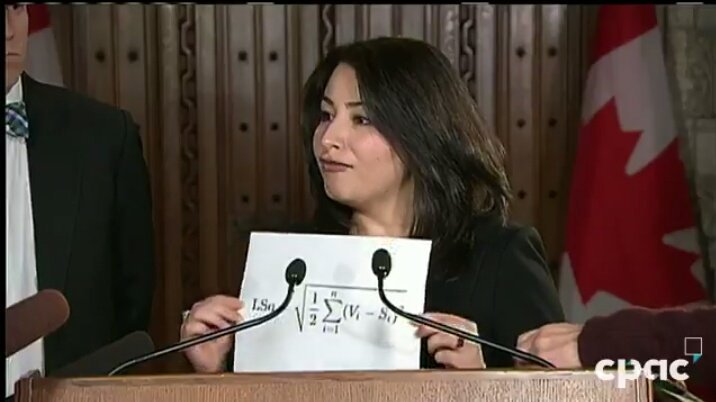

Similarly, when pressed by the host, Althia Raj, to state which voting system the minister was leaning towards (Monsef admitted earlier that she had a preference), she repeatedly deflected by saying she couldn’t see into the future and know what electoral system Canadians will choose.

Given the missteps with effective outreach during the consultation process, it was no surprise that in December Liberal members of the electoral reform committee said Canadians have not sufficiently been engaged in this process.

Clearly, I’m not alone in my concerns about inclusive consultation and we’re not on a promising path. I’d like to go back to the whole in-person engagement strategy and implement consultations that are widely advertised, announced far in advance, and always in accessible spaces. However, we’re farther along in the process, so I’ve been thinking of ways we can better leverage existing tools, like the much-criticized MyDemocracy.ca. Here is how I think even this tool and consultation process can be made more inclusive:

1. Advertise the process more widely

Although mail outs have gone out to draw attention to MyDemocracy.ca, many households might not receive or open them. Also, the deadline to fill out this survey has been moved from the end of December to January 15, but this news hasn’t been widely shared. To engage the wider swath of Canadians Monsef hoped for, this tool needs to be better publicized. It should then be shared in newsletters, by community organizations and advertised in public and democratic high-traffic spaces, including public transit.

2. Public education and plain language

For people to meaningfully engage with this tool and in electoral reform, they need to better understand the change that’s happening and the options that may be available. Once a user completes the survey on MyDemocracy.ca, they’re pointed to online tools that provide key information. Simply putting this on the front end and providing videos of town halls, infographics, or other visual tools could go a long way to helping survey takers give informed feedback. It would also be important to recognize that this topic is fairly dense and tools used to frame the conversation must be in simple and plain language.

3. Create More Space for Feedback on the current survey

Finally, the survey itself must be improved. One change that could happen is simply giving an open box at the end for people to feedback freely. This would lower barriers for anyone who may struggle to understand or accurately reflect their opinions in the multiple choice survey.

Uprooting a 150-year-old voting system in favour of one that is more representative of Canadians is no small task. Hiccups are expected. However, inclusion and a democratic process that all Canadians can access is non-negotiable and frankly, tied to the Liberals’ commitment to reach “beyond the usual suspects” in electoral reform.

Rudayna Bahubeshi is a city builder and communications professional deeply passionate about equity and civic engagement. She is the Communications Manager at Inspirit Foundation. You can follow her on Twitter at @Rudayna_B.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: CPAC