Politicians — and governments — are usually far smaller than the issues that plague us. Take the economy, for example. A good economic situation, by which I mean one where large profits are made, is a boon to incumbents; a poor one can prove disastrous to them. Yet domestic fiscal and monetary policy have about as much effect on global tides as witches dancing around a cauldron.

Governments during bad times are invariably in a defensive position, knowing how little they can actually do even with sterling acts of political will. Their response, therefore, is usually to ride the thing out, make a few highly publicized tweaks here and there, loudly blame the party previously in office, and hope for the best. The Opposition, for its part, blames the government in office, promises different tweaks that will make all the difference, and hopes for the worst.

Our economy, once again thanks to matters well beyond our control, is somewhat precarious at present. Cheap winter fuel and gasoline are bad for us, at least according to the mainstream economists, who do little more than pace capitalism, that weary marathoner, with shouts of encouragement. Our nascent status as a petro-state is faltering, thanks to OPEC’s untimely generosity at the taps.

There are, of course, short term quick-fixes and band-aids aplenty for tanking economies that can relieve a little of the pain, if not address the causes. But the economy as a whole is like the weather. Everyone talks about it, said Mark Twain, but no one does anything about it.

His point is actually a subtle one. We expect problems to get solved. And when we can’t do it ourselves, we expect “the authorities” to take over. Think the government won’t get blamed for bad weather? You’re wrong.

In a paper that all voters should read (but they won’t), “Blind Retrospection: Electoral Responses to Drought, Flu, and Shark Attacks,” political scientists Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels estimate that Al Gore lost approximately 2.8 million votes in the 2000 U.S. presidential elections, from electors in states that were either too dry or too wet at the time.

And, as the title of the paper suggests, it gets worse. While for a number of reasons the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 had no discernible effect on the electorate (even though the federal government’s laggardly response to the public health crisis arguably made things worse), a series of shark attacks in New Jersey in 1916 cost President Woodrow Wilson a significant number of votes.

So what is Harper to do? He can’t will the price of oil to go up. Nor, for that matter, can he make it stop snowing in the Atlantic provinces, or pluck sharks from the sea. But he can divert our attention.

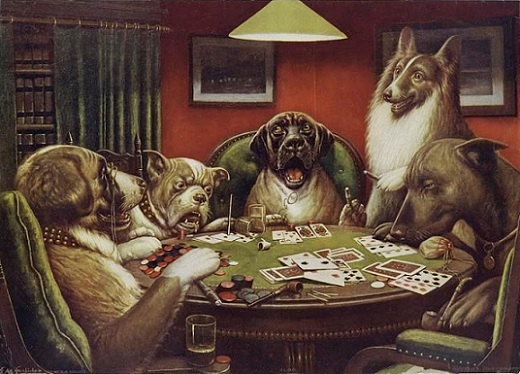

Classically, there have always been two broad approaches to winning popular approval, short of trying to have a real conversation with people whose choices have historically tended to be irrational. The first is bread and circuses: feed and entertain the masses rather than risk serious public policy debates. But free bread (welfare, in other words) is not the conservative way, and the grim and earnest demeanour of Conservatives doesn’t lend itself to carnival distractions either. Take Harper’s 24/7 video series, for instance. Please.

That leaves the other avenue: tell the people that they are under threat, and establish yourself as their protector. This tends to work like a charm.

Hence the time-honoured, multi-pronged strategy of fear is once again being trundled out. Harper is not holding back, either. We’re now involved in a new and rapidly expanding war. A dangerously broad “anti-terrorist” law, Bill C-51, is coasting through Parliament, with draconian time-allocation measures to ensure that it isn’t properly debated, and rigged Committee hearings. A scapegoat — Canada’s Muslim population — has been selected and targeted.

The latter initiative is already spreading like a stain, as these things tend to do. Despite a court ruling, the Harper government is still fighting to prevent Muslim women in religious dress from taking the oath of citizenship: even the hijab — a mere headscarf — may be banned, the Conservatives now suggest. A Quebec judge subsequently threw a woman wearing a hijab out of her courtroom, and was backed by the Court of Quebec.

The anti-Muslim backlash after the killing of two soldiers by murderous misfits last Fall has been greeted with official silence — that is, with complicity. In Shawinigan, Muslims were forbidden to build a mosque. The leader of Quebec’s third-largest political party suggested formal investigations before any new Muslim places of worship are opened in la belle province. Both the town council of Shawinigan and the politician in question have backed off, but much of the damage had been done.

Disabuse yourself of the notion, in case it is forming, that all of this nasty stuff happens within the borders of Quebec. Just read the comments following articles in the SUN chain of newspapers, or listen to a few call-in shows. Harper himself linked mosques and terrorism in a not-so-casual comment on Bill C-51.

All of this has been followed by artfully timed dog-whistles from Conservative pols: there were John Williamson’s remarks about “whities” vs. “brown people,” and Larry Miller’s injunction to women choosing to wear the niqab that they should “go back where they came from.” Both were followed by apologies — and broad winks to the base.

We can confidently expect this sort of thing to continue and even escalate during this election year. Canadians are being played for fools, and the polls show that they may be once again rushing in, although at least their collective enthusiasm for Bill C-51 has been cut in half since they started actually learning something about it.

The pressing political problem, for those of good will, has always been to find a way of engaging voters that does not appeal to their prejudices or leave their magical thinking unchallenged. How do we build such a radically new political culture, from the bottom up? At this point, to be honest, your guess is as good as mine.