I was in my mother’s kitchen when I heard the news on the radio: Jack Layton has lost his battle with cancer.

I was juicing watermelon and pineapple for my mother. She is a survivor of laryngeal cancer who can eat no solid foods. I was shocked, but I wasn’t surprised: I’d seen Layton’s July press conference, his face already a death mask. I stopped what I was doing, steadied myself against the kitchen counter and just felt terribly, terribly sad.

I tried to swallow back the salt water in my eyes. I didn’t want to upset my 84-year-old mother. But she heard, of course, and got upset, and we mourned together, in our own way. As a dry prairie wind blew against the windows of her condo, I read Layton’s “Letter to Canadians” to her. We both got choked up. I’d never in my life grieved a politician’s or celebrity’s death: not Diana, not even Pierre. But I knew that our mourning was mixed with other losses: for my dad (cancer) and my brother (heart attack and poverty); for her friends who had recently passed.

Embodied feeling — lumps in throats, watering eyes — was evident all day, with me and my mom, and among my friends, but also on TV. Hardened broadcasters who had never in their careers expressed sympathy for social democracy or the left got hoarse of throat, or flushed of face as they tried, and failed, to remain impassive. I watched friends or relatives who had never really been interested in Layton as a person or as a politician, expressing an ineffable grief. The affects of sadness, grief, embarrassment, pride became contagious: they mingled and transformed one another in the contact zones of kitchens, city squares, and even taxi cabs.

For me, as someone who studies affect — embodied feeling within culture — the televised funeral of a government leader or monarch provides a fascinating opportunity to study contagious feelings and contact zones. In my recent book, Feeling Canadian: Television, Nationalism and Affect (WLU Press 2011), I devoted a chapter to the October 2000 state funeral of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. I wrote about how, since Princess Diana’s funeral, or perhaps even since the funeral of JFK, televised celebrity funerals make people cry for someone they’ve never met in part because they meet a need to “see oneself as fully human and of this world, and therefore, affected” (113).

On Aug. 27, I attended the People’s March to accompany Layton’s coffin to his funeral at Roy Thompson Hall in Toronto with my friend The Poet. Was I doing research, or participating in a collective experience of mourning? I know that I wanted to experience the event without the extreme mediation of television, Internet and media (though of course my perceptions had already been impacted by them). More and more, I’m finding I want more proximity to those ideas, events or figures I theorize. But I also just wanted to be there, for reasons I didn’t fully understand.

I teared up when I saw people slowly walking towards City Hall in orange T-shirts or the black clothes of mourning. This was such a strange, dignified, hybrid event: part funeral, part political gathering, part festival.

I felt embarrassment as I joined the crowds trying to get a glimpse of the coffin. When The Poet told me why she was there, I felt interest, and a flicker of shame at my own skepticism. I was a political refugee, she said, and a victim of torture in my country. I came here with nothing. Three years passed as I tried to get refugee status. I asked Jack Layton and Olivia Chow to write a letter. I finally had my hearing: it took three minutes and my application was accepted. They phoned the day after to make sure it had gone OK. In the last election, I voted for the first time as a Canadian citizen. Yeah, I’m critical of the system too, but I voted because of Jack.

We watched Layton’s wife, Olivia Chow, lead the procession, walking alone: so stately, so regal, so masculine, somehow, in the way she took up that space. We walked with random folks, and more specific ones: sad Quebecois clowns; immigrants; trade unionists; a postal worker in uniform (the NDP staunchly supported their last strike); many members of the Chinese community (Olivia is Chinese-Canadian, and Layton had learned to speak Cantonese).

As political as Layton’s final letter was, the march itself seemed muted. I wondered why I only saw one sign protesting our current far-right government. Despite Layton’s call to “change the world,” I wondered if this particular kind of collective, contagious affect that circulates around public figures is antithetical to grassroots organizing.

Later, I watched the funeral at home, alone, on TV. It was here, outside of the contact zone of the street, that I found myself most deeply affected: by the aboriginal blessing by Shawn Atleo, leader of the Assembly of First Nations; by Stephen Lewis’s very fine, very pointed, and very activist eulogy. I also noticed how, with every such outspoken moment, there would be a gesture of containment, whether by the minister Brent Hawkes’s seeming attempts at watering down Layton’s message, or by the TV camera’s framing, with several closeups of Prime Minister Harper or former Liberal prime ministers, which seemed to want to “balance” the closeups of Olivia Chow and her family.

I had closely observed the rather conventional, contagious affects of the Trudeau funeral. But this event was different in several ways. Here, the left and the marginalized were now in the centre of things (at least outside Roy Thompson Hall). Queerness had operated at the Trudeau funeral week like a shadow, or a trace; a rumour; subliminal references to Trudeau’s sexuality. Here, queerness was front and centre: queer pastor, lesbian singer. But it was a normalized queerness that operated that day. Hawkes with his Order of Canada medal, his insider references. People of colour, immigrants, refugees, trans folk — they were all outside the church, standing in a square in the hot sun.

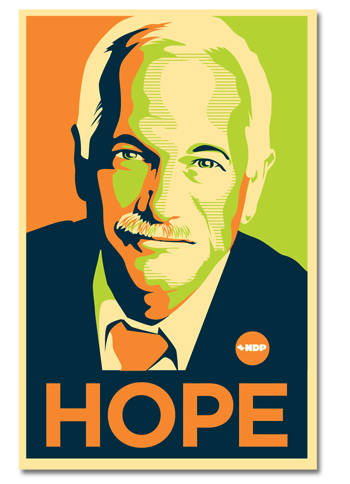

Love. Hope. Optimism. These were the keywords of the week, drawn from the conclusion of Layton’s letter. In that sense, positive affect was at the heart of things, but this was, perhaps the affect of elites, of the elect. It reminded some of us of Obama’s hope/change mantra. It made us think of Sarah Palin at a Tea Party convention, nastily addressing Obama in the throes of his comedown from popularity: How’s that hopey-changey thing workin’ out for ya?

Perhaps it is, necessarily, the job of politicians to be hopeful and optimistic — but should a homeless person, a person with AIDS, a woman dying with breast cancer, feel hope and optimism? I remember how angry my friend France Queyras, an artist who died of breast cancer, was: at the environment, at the Cancer Society that spends millions on advertising, on overhead, on looking good and feeling better, and that couldn’t even cover the cost of her vitamin supplements, let alone on research into the environmental causes of this horrible epidemic. My mother, now on her third bout of cancer, is certainly not feeling optimistic. I’m not feeling the love for a far-right government that has cut everything that I believe in, from child care to women’s groups, to arts funding. Along with most Canadians, I was outraged when, under Chretien and then Harper, we joined the wasteful deadly war in Afghanistan, and then the bombing in Libya (sadly, the NDP supported the latter). I believe it is the job of activists to feel the anger along with the hope that our solidarity and our activism might manifest.

After the march and the funeral, I can say that I felt excited. Uplifted, perhaps. But it was an odd, uneasy feeling, like the kind of thrill I get at spotting a celebrity on the street during TIFF. It doesn’t last; it won’t last.

What has lasted, what has stayed with me, is the chalk memorial at City Hall.

On Monday, two days after the funeral, I went there after work. The chalk inscriptions had spread, like something wonderfully viral and contagious, from the concrete floor and walls of the square to the walls and doors of City Hall itself.

People were still chalking their comments where they could. A girl knelt quietly in front of the makeshift memorial full of orange flowers, orange crush cans, handwritten condolence notes. City workers, moms with strollers, walked around solemnly, reading the inscriptions.

It was a silent, yet voluble Babylon of languages, where the specificity of Layton’s activist history — purposefully censored out, I believe, in standard media accounts of the man before his death — were brought back to life. Thank you for attending Pride. Thank you for helping to bring my grandparents to Canada. And on and on.

This was an unofficial memorial, more visceral, more affective than any book of condolences. Unbearably ephemeral, it will be gone by the next rainfall. There was grief there, and love, and humour, and interest — the deep abiding interest and love of citizens, — in their city, in their bike lanes, their solidarity movements, their trade unions and their protests. It wasn’t just about Jack anymore, and while it did have that strange sense of people joining in just to be part of something, it had so many other affects, too.

Jack Layton’s death became mapped across an incredibly diverse and polyphonic social body. Cancer survivors like my mom. Refugees like my friend. Queers, and socialists and environmentalists and Quebecois. In some ways the outpouring of feeling may have had less to do with Jack, and more to do with us, as citizens of a city and a nation, whose feelings and voices managed, in that ragtag, DIY memorial, to move beyond the limits of electoral politics and nationalism.

That gives me hope, that rare, tempting and elusive affect. Such a multi-ethnic and multi-issue coalition may indeed change the world — or, at least, bring down Harper.