Canada’s dreary record on Indigenous rights – especially our residential school system – might put this country in a unique position to work for human rights reforms in China.

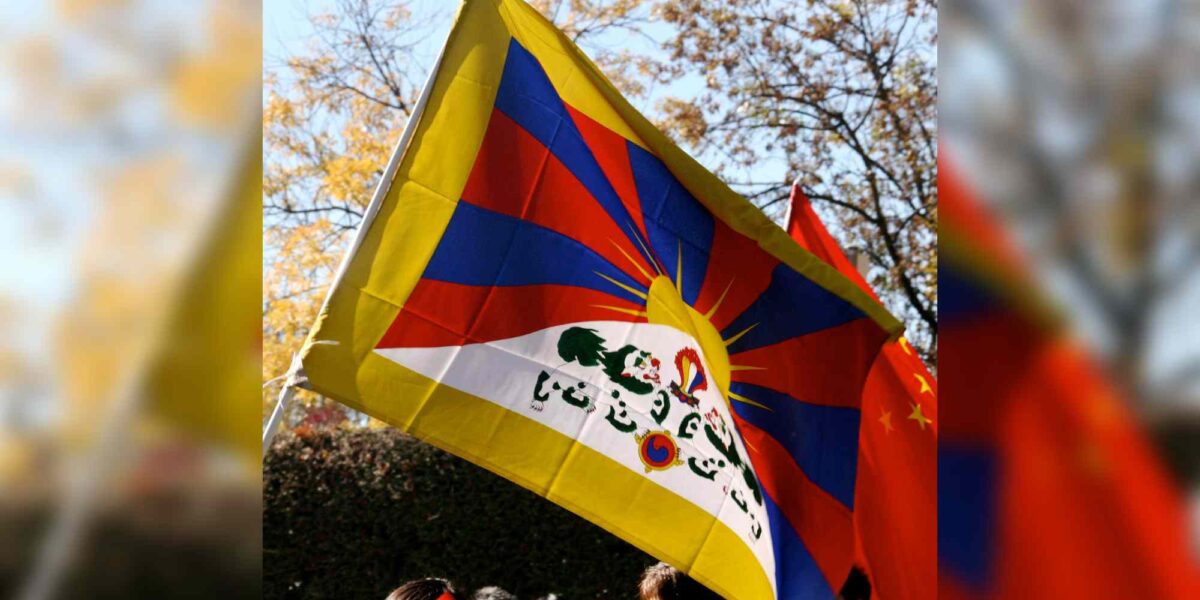

So says a new House of Commons committee report on the formerly sovereign country of Tibet, which, since 1949, has been controlled by China.

The report of the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee was tabled shortly before the House of Commons rose for the summer, and has the support of all four parties in Parliament.

The committee focused on the human rights situation of Tibetans generally, with a special focus on China’s residential boarding school system.

In theory, the report points out, Chinese law “provides protections for ethnic minorities and guarantees minority-language rights.”

The report quotes the Chinese law on religion and ethnic minorities, which states that “schools where most of the students come from minority nationalities should, whenever possible, use textbooks in their own languages and use these languages as the media of instruction.”

Chinese practice, however, especially under President Xi Jinping, has been quite different from what is prescribed by law.

Attempt to erase Tibetan identity

The report tells us there are an estimated 800,000 Tibetan children who are currently attending residential schools, accounting for 78 per cent of all Tibetan children aged six to 18.

A further 100,000 children aged four to six attend one of more than 50 boarding preschools. These preschools, for the youngest Tibetan children, are a recent Xi Jinping regime innovation.

The most significant consequence of the Chinese version of the residential school system is “the separation between children and their parents and wider communities.”

This separation, witnesses told the Committee, is happening, as it did in Canada, against the will of parents and children.

The report quotes Tibetan Canadian activist Lhadon Tethong, who said parents have “no choice but to send their children to live in these schools, because the authorities have closed the local village schools” and the children “are forced to go to boarding schools.”

“In some cases, the children cry for days,” Tethong said, a fact that will resonate with Canadians familiar with our residential schools for First Nations children.

The all-party report states that the most pernicious aspect of the Chinese residential school system is something that will, again, sound familiar to Canadians: “the replacement of the Tibetan language and cultural practices with Chinese language and culture.”

Lhadon Tethong characterized the Xi Jinping government’s targeting of language and culture as “the cornerstone of a broader effort to wipe out the current and future resistance of our fiercely proud Tibetan people by eliminating our language, our religion and our way of life.”

Witnesses told the committee the Chinese government’s aim is to change the identity of Tibetan children. As did Canada’s governments for many generations, the current Chinese government wants to erase all traces of Tibet’s distinct culture.

Canadian authorities long believed stamping out Indigenous languages was key to eliminating the notionally primitive and backward “Indian” way of life. Today’s Chinese authorities have almost exactly the same view with regard to the Tibetans.

When children lose their language they can no longer communicate with older generation members of their own community and they lose a vital connection to their history and traditions.

Lhadon Tethong put it this way:

“Tibetan children below a certain age are fast becoming native Mandarin speakers, which means they can no longer converse meaningfully with their parents and not even communicate with their grandparents…If children inherit genes from their parents, it can be said they inherit culture from their grandparents.”

The committee report does not focus exclusively on residential schools in Tibet.

It also comments more broadly on the full gamut of Chinese human rights violations in the formerly independent country of Tibet. It quotes one member of the Tibetan diaspora who said “the Chinese government’s assault on Tibetans has reached a breaking point.”

The Chinese government has undermined Tibetans’ religion, Buddhism, by banning prayer flags and the building of Tibetan Buddhist statues. The Xi Jinping government has also created “management committees” for Tibetan monasteries, where Chinese Communist Party members oversee and monitor all aspects of the monks’ work.

In addition, the Chinese government has used the pretext of ecological protection to move traditional herding communities away from their high-altitude communities to villages far from their traditional territories.

Toronto-based human rights advocate Chemi Lhamo told the committee: “Millions of nomads have been relocated from the grasslands into reservation-style housing projects… with little to no access to jobs.”

Canadians who have looked into our own reserve system for First Nations peoples will find the current Chinese practice to be eerily familiar.

What Canada can do

The Foreign Affairs committee argues, without irony, that “Canada is particularly well-positioned to lead on this issue, given its acknowledgment of the major harms caused by its own twentieth century system of residential schools designed to assimilate Indigenous populations into the majority Euro-Canadian population.”

There are two sides to that coin, of course.

The Chinese government has attempted to dismiss Canadian objections to its human rights abuses based on Canada’s own blemished record.

In response to that objection, the committee quotes Canada’s ambassador to the UN, Bob Rae, who makes a distinction between 21st century Canada and contemporary China.

“We in Canada have established commissions of accountability,” Rae said. “We have established commissions of Truth and Reconciliation. Where are the commissions of truth and reconciliation in China?”

The report makes eighteen recommendations for Canadian government action, ranging from taking in more Tibetan immigrants to funding academic research on Tibet to sanctioning Chinese government officials responsible for the implementation of the residential school system.

Samphe Lhalungpa, a retired UN professional and Chair of the Canada-Tibet Committee, says the June 2023 committee report is the most thorough of any the Canadian government has ever done on Tibet.

“This report,” Lhalungpa says, “is very welcome as it highlights the vastly increased levels of repression by the Xi Jinping regime that is aimed at nothing less than the ‘sinicizing’ of Tibetans, by draconian restrictions on manifestations of Tibetan linguistic, religious and cultural identity.”

As for what Canada can now do, Lhalungpa recommends “the government of Canada and its constituent parts develop a coherent and comprehensive set of policies, not just salami slice some half measures to placate Canadian activists and the Tibetan diaspora.”

The need is urgent, the Ottawa-based advocate says, because of China’s increasing economic clout.

“Tibetans on the high plateau of the Himalayas have been struggling for decades, but are now faced with a Chinese government fattened by the profits of becoming the world’s factory. China now has the economic means to bring the full weight of its resources — financial, security, technical, political and electronic – to their longstanding project to ‘de-Tibetanize’ Tibet. Nothing less.”

This committee report is an example of all parties in the House putting aside the rampant partisanship that seems to dominate so much of current politics to tackle the too-often-ignored human rights abuses in a far-off, isolated part of the world.

The committee deftly tried to leverage this country’s own historic efforts to “de-Indigenize” our First Nations peoples to this country’s advantage.

We now have to hope the Chinese government does not use Canada’s dreadful example in the opposite way, as did the white South African regime when it introduced Apartheid – as a road map to push forward its eradication mission in Tibet.