A public inquiry into foreign political meddling must go beyond China and other foreign governments. It should include powerful non-state actors. Jason Kenney’s UCP government created a precedent for this in 2019 when it called a public inquiry to investigate what it alleged were vast sums of U.S. foundation money that flowed to Canadian environmental groups to landlock Alberta oil. Unfortunately, the episode was a lesson in how not to conduct a public inquiry.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) instigated Kenney’s public inquiry shortly before the 2019 Alberta election, when, it charged that foreign-funded, anti-pipeline activists made a ”concerted effort to shut down our industry.“ Kenney heard the call and promised a public inquiry and war room four days before the election. CAPP is Big Oil’s apex lobby group.

The whole episode shows the perils of promising a public inquiry into a phantom enemy. It helped Kenney’s newly created United Conservative Party defeat Rachel Notley’s NDP in 2019. But after winning, Kenney was stuck with his rash promise and appointed Steve Allan, a forensic accountant, to head the public inquiry. Selecting a forensic accountant made it look like environmentalists’ actions to curtail oil sands emissions and production were illegal. But Allan’s inquiry was a nothingburger. It found no improper or illegal activity and only a pittance of annual foreign money, a sum that was less than the cost of the inquiry itself.

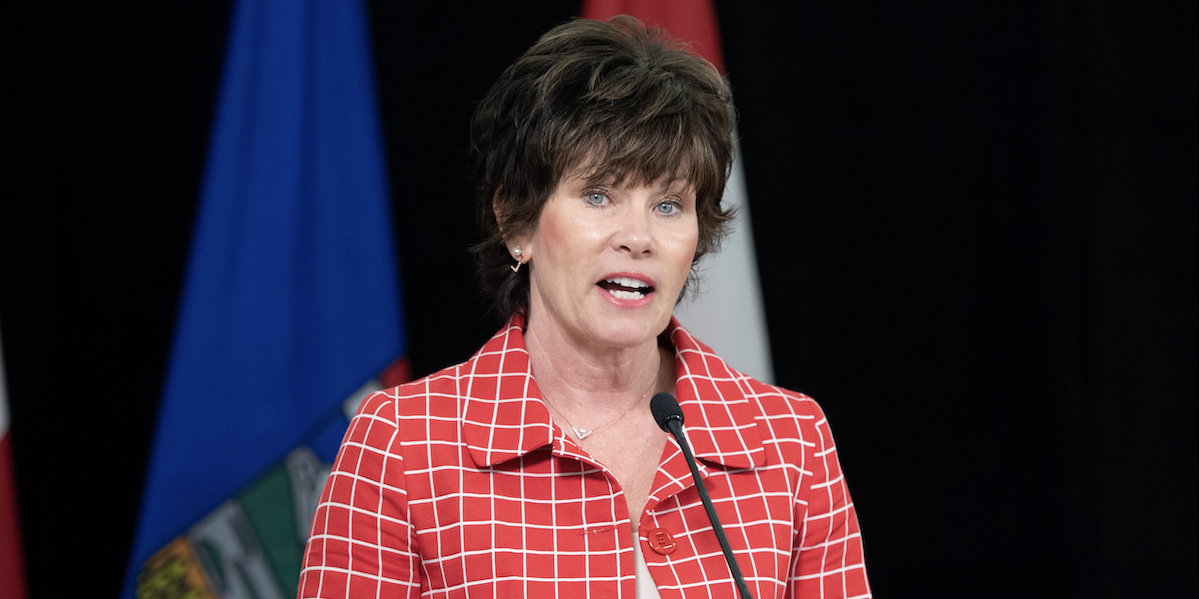

When she released the public inquiry report, Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage called it a “real concern” when any group is “influencing political and regulatory change using foreign funding.” Good call, but if so, why did her government not go after the main foreign-funded political meddlers — big oil corporations?

All major oil corporations operating in Alberta and Canada are majority foreign-owned. Foreign-owned means foreign-funded and foreign-influenced.

Kaycee Madu, who was then Alberta’s justice minister, followed up Allan’s inquiry with Bill 81. It purportedly curbed foreign political interference. “Elections must remain a time for Albertans to discuss and determine the fate of their province — without undue foreign influence,” Madu stated. He promised that his bill would ban foreign money from Alberta elections.

Unfortunately, it did no such thing because it failed to prohibit foreign-funded political interventions by the principal sources — foreign-owned corporations operating within Alberta.

Embarrassed that the inquiry was headed by a prominent accountant, the Canadian Accountant, the normally staid newspaper of the national accounting profession called it a “shambolic fiasco of a public inquiry.” Public inquiries usually hold public hearings. This one did not. Instead, it conducted a very costly ($3.5 million) Google search for information that was already in the public domain.

Alberta had aimed at a mole hill instead of the Rockies. Right under its nose was a far larger source of outside money influencing Alberta and Canadian politics — big foreign oil. They dominate CAPP. Although it gaily waves the Maple Leaf, research shows that 77 per cent of CAPP’s 2020 corporate board members were fully or majority foreign-owned.

CAPP does not publicly reveal its total revenue, but we can assume that about 97 per cent comes from its foreign-owned, foreign-funded corporate members. They produce 97 per cent of the oil and gas generated by CAPP’s board members. CAPP member fees are proportionate to their oil production levels.

CAPP employs 36 full-time lobbyists and runs Canada’s Energy Citizens (CEC), an influential front group that poses as citizen-led. Before the 2019 federal election, CAPP’s CEC ran a “Vote Energy” campaign to counteract rising support for climate action. It was code for vote Conservative.

Using its foreign funds, CAPP was a registered third-party advertiser in the 2019 federal election. As such, it could spend up to $1.5 million before and during the election period and run ads supporting candidates and parties. Can you interfere in elections with foreign funding more than that?

The lesson from Alberta’s sorry inquiry episode is to not to dismiss a public inquiry as hopelessly partisan but to stress that it be impartial and independent of government. It must report to Parliament, not to government and have a broad enough scope to include major non-state, foreign meddlers.

This article was originally published in The Edmonton Journal.