Back in January 2019, observers of the Alberta political scene wondered if the $6,000 administrative penalty levied against the Canadian Taxpayers Federation (CTF) for failing to register as a third-party advertiser under Alberta’s election financing law would result in a long-overdue recognition of the partisan role the self-described “tax watchdog” clearly plays in Canadian politics.

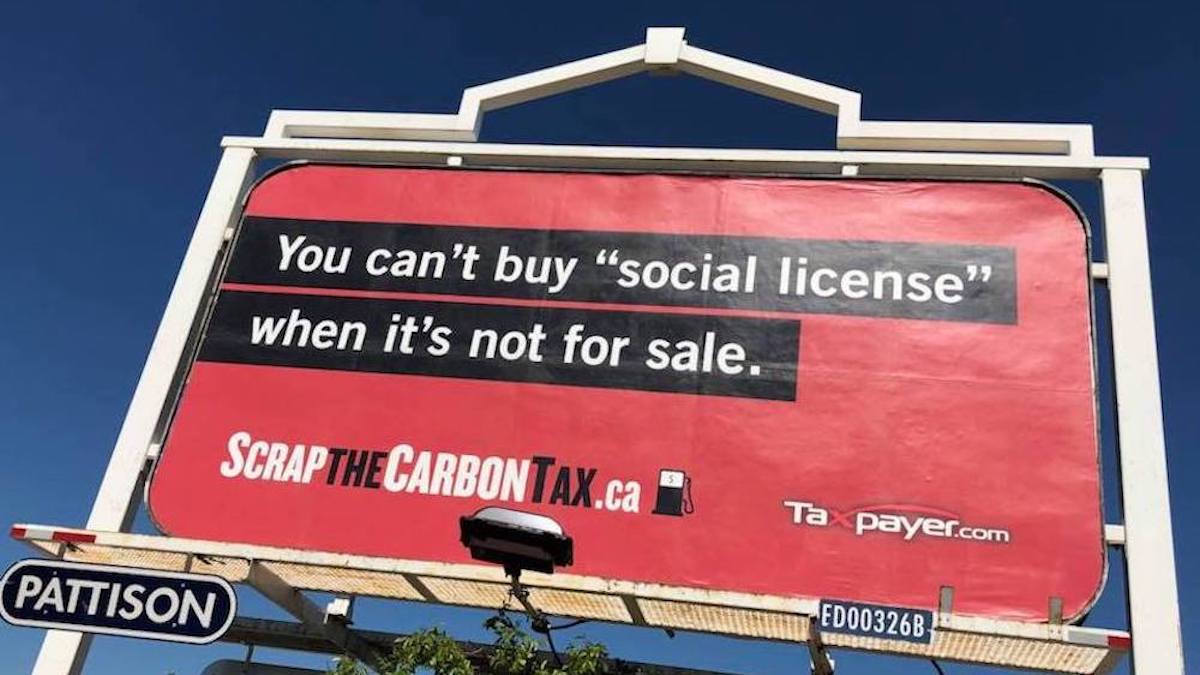

The CTF, disproportionately influential in Canadian political discourse in large part because mainstream media organizations treat its questionable pronouncements as if they are credible, had purchased a couple of billboards the previous summer attacking the NDP’s carbon levy and the government’s argument it could win “social license” to build more pipelines to the West Coast.

“You can’t buy ‘social license’ when it’s not for sale,” the billboards proclaimed, which is a position a reasonable person could argue, although the opposite is more likely true.

Be that as it may, the CTF’s problem had nothing to do with the merits of its argument or its right to state it, but with the requirement in Alberta law that anyone spending more than $1,000 on election ads had to register with the election commissioner as a third-party advertiser.

“I believe that the CTF intended to convey a message in opposition to an issue associated with the leader of a registered political party and it was fully aware of the requirements for third party advertising registration,” said Election Commissioner Lorne Gibson in a 2018 letter to the CTF.

“So the $6,000 question,” I wrote at the time, “is whether this development will make media more cautious about acting as if CTF claims come from an unbiased and disinterested source?”

Fast-forward five years to last Wednesday and Justice Grant Dunlop of the Court of King’s Bench in Edmonton dismissed the CTF’s appeal of the fine, stating in his decision that “none of the three grounds of appeal relied upon by the Federation is established.”

The CTF had argued the election commissioner had failed to consider relevant evidence, that he also failed to consider that the organization intended to use the penalty as a test case of the constitutionality of the law, which should have mitigated the penalty, and that he failed to provide reasons why he raised the fine to $6,000 after saying he was considering a $1,000 penalty.

CTF President Scott Hennig told the Edmonton Journal this week that the organization will not appeal Justice Dunlop’s decision but will continue with its constitutional challenge of the Election Finances and Contributions Disclosure Act later this year.

Really, though, as things stand now Hennig has little cause for complaint. The fine’s pretty small in the great scheme of things – a fine example of white collar privilege, as it were.

And by late November 2019, former United Conservative Party (UCP) premier Jason Kenney’s government had passed legislation firing Gibson and moving the work of his office to that of the Chief Electoral Officer.

A few days after that, the CBC revealed that a lawyer for the Kenney Government’s justice minister tried to talk a judge into putting off the CTF’s challenge of the act on the grounds the government planned in 2020 to “rescind or amend part of the election finance act” the next spring. I guess it’s always good to have a former CEO of your organization in the Premier’s Office.

Then, in March 2022, changes to the Election Act and Election Finances and Contributions Disclosure Act in the Election Statutes Amendment Act of 2021 came into force, including the removal of “an advertising message that takes a position on an issue” associated with a party, MLA or leader from the definition of political advertising.

More recently, last November under the Danielle Smith Government, the Standing Committee on Legislative Officers indicated it would be seeking a replacement for Glen Resler, the chief electoral officer.

With a co-operative government and a compliant media, the CTF needn’t have worried very much.

Yes, the CTF continues to insist it is non-partisan, which in a technical sense is true since it doesn’t openly advocate for any political party by name. But as a practical matter it remains part of the strategic infrastructure of the Conservative Party of Canada and the federal party’s provincial branches doing business under a variety of names.

Beyond delivering a mild sensation of schadenfreude, at this point, the possibility a mere $6,000 fine would deliver a fatal blow to the dubious credibility of the CTF in Canada’s moribund media ecosystem seems quaint.

Still, it probably explains the secretive organization’s decision just to pay the penalty and be done with it. After all, why draw attention to something that otherwise might chip away at your credibility?