Sixteen is presently being considered as the new minimum voting age in BC, with support from a former Canadian Chief Electoral Officer. That’s no surprise: the idea has been around for quite a while now. A Bill to extend the franchise to 16-year-olds was introduced (and defeated) in Parliament as long ago as 2005.

A more recent attempt in PEI was unsuccessful; a similar Bill has just been introduced in Ontario.

The measure has already been implemented in Austria, Malta, Nicaragua, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Jersey, and Guernsey.

It’s no surprise that the proposal is being immediately red-lighted by some. But Andrew Coyne, not exactly partial to the idea, may be on to something–perhaps without knowing it.

Why not extend the franchise to children, he asks rhetorically. Or cats, for that matter? He’s getting at an illogical counter-argument, of course (the fallacy of the converse)–old arguments against giving women the vote, or lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, cannot simply be reversed to claim that any group should be given the vote. But (setting cats aside) why not let the kids vote?

“But they don’t know enough,” some will cry. Okay, give sixteen-year-olds the vote, others say, but make sure they get a good grounding in civics to qualify.

But this is, with respect, the wrong way to frame the discussion. Instead, why don’t we step back and look at voting behaviour in general?

Democracy is a messy business. We all know people who vote for “the wrong reasons.” They like Justin Trudeau’s hair (or dislike it). They’re mad as hell and don’t want to take it any more. Andrew Scheer seems like a nice young man. Jagmeet Singh is different (which can be either a plus or a minus).

Meanwhile, you agonize over your vote: you assess party policies and how they align with your own values, you wonder whether you should vote strategically, you look at the various parties’ records in office, you listen to the candidates in your own riding and assess their merits in terms of what they are saying, how they are saying it, whether they have the right qualities to represent you in Parliament, and so on. You know how the system works. On E-Day, you go into that booth prepared.

But you are in a minority. A small minority.

In 1964, Philip Converse wrote his now-famous classic on voter behaviour, “The nature of belief systems in mass publics.” He identified five strata of voters, the first two of which voted, entirely or at least to some degree, on the basis of political considerations: added together, these two groups were about 15.5% of the whole. Most others voted on the basis of perceived group interests (a largely instinctual matter for them that bore little or no relation to policy), or were single-issue voters. The fifth stratum, comprising more voters than the first two groups combined:

…included those respondents whose evaluations of the political scene had no shred of policy significance whatever. Some of these responses were from people who felt loyal to one party or the other but confessed that they had no idea what the party stood for. Others devoted their attention to personal qualities of the candidates, indicating disinterest in parties more generally. Still others confessed that they paid too little attention to either the parties or the current candidates to be able to say anything about them.

But that was then, more than half a century ago, and this is now. Surely things have changed since, with so much almost instantaneous information available to everyone, right? Well, apparently not.

Two political scientists, Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels, have been tracking voter behaviour for nearly two decades, focusing upon a phenomenon called “blind retrospection,” where voters punish or reward political representatives for matters well out of their control. In 2002, they presented some disconcerting findings: shark attacks in New Jersey significantly affected the vote for Woodrow Wilson in 1916. While this specific conclusion has been disputed, their general view of voting behaviour has not. In 2004, they were able to establish that Al Gore, running against George W. Bush, lost seven states because there was either too much rain, or too little. 2.8 million voters in those states wanted to punish the incumbent government for bad weather.

Their conclusion:

Our formal model is based on the assumption that voters do behave rationally. However, our empirical evidence is equally consistent with a political psychology in which retrospective voting has more in common with kicking the dog—or with the superstitious tendency of earlier peoples to punish their own leaders for droughts, plagues, or volcanic eruptions than with…rational assessments of blame or credit.

The point to stress here is that most voters do not vote the way that a few of us politically-engaged types might have imagined. In this wider context, the flap about giving young people the vote because they wouldn’t choose wisely seems to be seriously misplaced. At its worst, the vote of children would make no difference whatsoever to the outcome of an election, so we might as well give it to them. At its best, judging perhaps hastily from the recent children’s crusade in the U.S., it could make a significant difference–for the better.

We needn’t make strawman arguments to bolster the case for a genuinely universal franchise. Nor should we adopt Demeny voting, in which the children’s vote is delegated to parents: that’s a perfectly dreadful idea that privileges parents over all other voters, and leaves children as disenfranchised as before.

Even without mandatory civics classes from grade school on–which should be encouraged–we can reassure ourselves that schoolchildren likely know as much and care as much about the system in which they are engaging as do most older folks today. The youth demographic traditionally has a low voter turnout, but, in Canada at least, this is changing. If 18-year-olds are becoming more engaged, why not encourage those even younger to do the same?

Promoting civic involvement in our schools, and encouraging our youth to develop the voting habit early, could each have beneficial effects on our democracy, and in combination would certainly do so. And, taking the long view, the next generations of electorates, fortified with more knowledge and voting experience than anyone today, would be likely to vote more wisely and rationally between policy choices–rather than hate-voting because of an above-average snowfall.

It’s hard to see the downside, when you think about it.

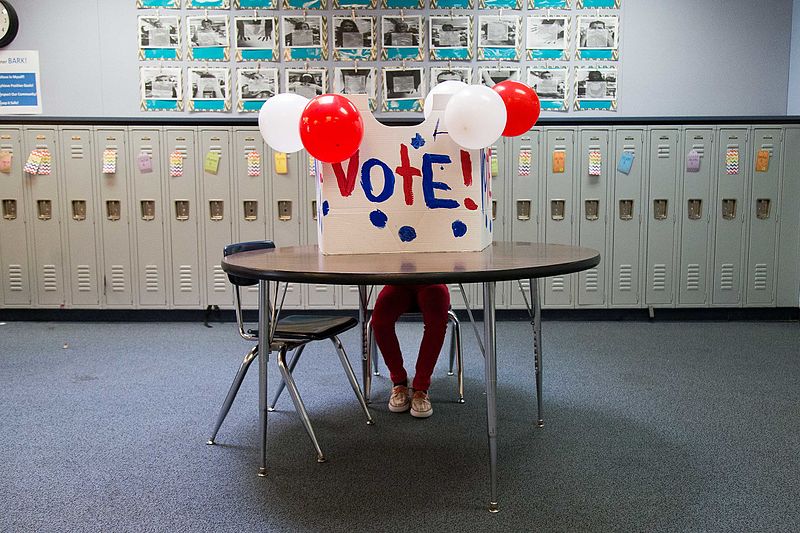

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.