rabble.ca is a reader-supported site — we count on donations from people like you. Please join us as a paying member (click here) or send a one-off donation (click here) to help us continue our work.

This is the second in a four-part series for rabble.ca. To read last week’s introduction, please click here.

Dustin King was looking for help when he knocked on the door of Donna Bertrand’s apartment at about 3 a.m. on Nov. 21, 2008. The troubled 19 year old was upset after a fight with his father.

“He needed someone to talk to… he picked me because I am a nurse and he actually respects me,” Bertrand told police. The two of them talked, smoked a joint, and at about 7 or 8 a.m., King went to sleep on her couch, she said.

But by 4:30 p.m., King was still on the couch. “He had a lot of foam bubbling out of his nose, his eyes were closed, he was very blue . . . and very cold to the touch,” paramedic Meggie Cashman told the first day of a Brockville Ontario coroner’s inquest, last week.

Just 11 days after King’s death, 41-year-old Bertrand herself was found face down on the floor, next to the same couch. Her body had apparently lain there for two or three days before a young man broke into her apartment and noticed a disturbing smell.

Ontario is in the midst of a prescription opiate public health crisis — that’s how even the normally staid College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario has labelled the situation. It’s not the only province with a problem, but it has the highest rate of prescription narcotic abuse in the country.

The inquest, which began June 2, will include “an examination of the issues of prescribing, diversion and monitoring of opiates” as they relate to the deaths of King and Bertrand, the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services release states. It was called to “draw community attention and response to preventable deaths,” presiding coroner Dr. Roger Skinner said in his opening remarks.

But an inquest is a story that begins at the end. It must explore the events surrounding death, and so the first two days focused on pathologist, police and paramedic reports about the two deaths, photos of the scene of the deaths, and witness statements from friends of the deceased about their final days and hours.

Both King and Bertrand were part of a Brockville drug subculture known to police, but it’s not only those “on the margins” of society that have problems with prescription drugs. Think of Heath Ledger.

King’s death was “consistent with oxycodone toxicity,” pathologist Dr. Samuel Ludwin testified. The level of oxycodone in King’s blood (0.46 mgs per litre) “was consistent with fatal overdose. If a patient was tolerant they could survive with this, but this was in the fatal range.”

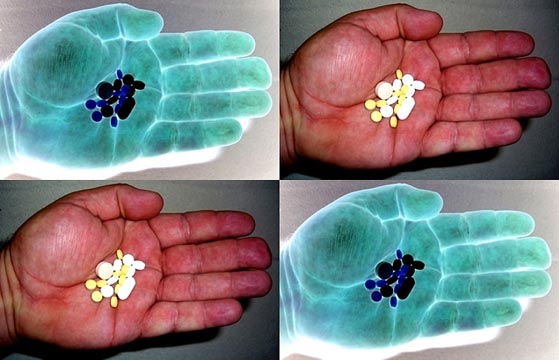

Among the prescription pill containers that police seized from the apartment, the label on one container said it had been filled Nov. 20 for Donna Bertrand, and contained 180 tablets of Oxycontin 80 mgs tablets (oxycodone is the active ingredient in Oxycontin) with instructions to “take 3 tablets 4 times a day”. Another pill container for Oxycontin prescribed for her was dated Nov. 10.

But Bertrand’s own death was due, not to oxycodone toxicity, but to elevated levels of a mixture of the anti-depressants Paroxetine and Venlafaxine and anti-psychotic Prochlorperazine, testified pathologist David Hurlbut.

Bertrand’s third floor apartment at 89 King St. West in downtown Brockville was in a building known to police for drug use. On the first floor was an apartment known as a “crack shack” where addicts snorted and injected Oxycontin as well as illegal drugs like cocaine, speed and heroin.

Natasha Valiquette, 28, testified that she was addicted to Oxycontin that she bought on the street and injected, and that early in the morning of Nov. 21 she had been in the downstairs apartment. King was also there: “He was drinking, he was upset” because of an argument with his father, she said. When she went up briefly to Bertrand’s apartment the morning of Nov. 21, probably around 9 a.m., Valiquette said she heard Dustin snoring.

Bertrand said she had stayed up until late morning — she had left the apartment at about 9:30 a.m. to buy some food and pick up another prescription for Oxycontin — and fell asleep at home in the late morning.

She was woken telephone call at about 2:30 p.m. “I went over to kiss him [Dustin] on the forehead to wake him up . . . I noticed he wasn’t breathing,” she told police. “I just lifted his arm and put it across his chest . . . I think it was a nursing habit. I was a nurse for 19 years.”

“Donna screaming that Dustin was dead” was what woke up Lisa Whitmore, who had also been asleep in Bertrand’s apartment. Whitmore, 43, told the inquest that she had been up and down between Bertrand’s apartment and the main floor crack shack throughout the night and morning. High on speed and coke, she had not slept for four or five days, and fell asleep shortly before Bertrand’s scream work her.

The two deaths proved to be a wake-up call for Whitmore and Valiquette. Both women told the inquest that they are now on a methadone maintenance program, which they began shortly after the 2008 deaths.

The inquest continues.

Ann Silversides has a Canadian Institutes for Health journalism award to research issues related to prescription painkillers.

Thank you for choosing rabble.ca as an independent media source. We’re a reader-supported site — visited by over 315,000 unique visitors during the election campaign! But we need money to grow. Support us as a paying member (click here) or in making a one-off donation (click here).