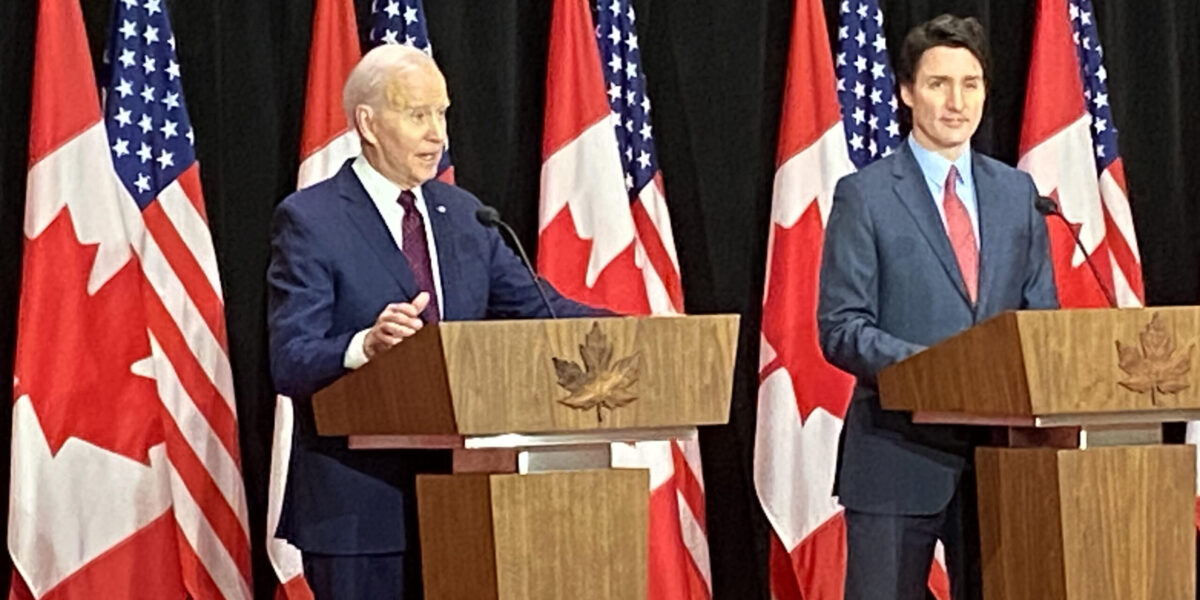

Canada shares a land border with just one country. It is the longest border in the world. That border was at the heart of discussions between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and President Joe Biden during the latter’s visit to Canada’s capital late last week.

The result of those discussions was a commitment from the U.S. to expand the decades old Safe Third Country Agreement and that Canada in return would accept an additional 15,000 refugees from the Western Hemisphere.

For years now there has been a mass migration from Central and South America into the U.S. and Canada. These are refugees seeking safety from war, gang violence, poverty and destruction in their home countries caused by the climate crisis.

Some of these refugees travel through the U.S. and into the safety of Canada. In recent years many have crossed into this country irregularly through Roxham Road border checkpoint in Quebec.

Is the U.S. a safe third country?

The Safe Third Country Agreement between the U.S. and Canada came into effect at the end of 2004.

The agreement effectively requires refugees to be settled in the first safe country they arrive in after fleeing their home country. If they arrive in the U.S. first for example, and then cross into Canada at an official port of entry and attempt to claim asylum, they will be returned to the U.S. because of this agreement.

The new arrangement announced on Friday, March 24 now extends the agreement across all points of entry, including irregular border crossings like Roxham Road, which Prime Minister Trudeau announced would in fact be closed entirely.

“Both of our countries believe in safe, fair and orderly migration, refugee protection, and border security. This is why we will now apply the Safe Third Country Agreement to asylum seekers who cross between official points of entry,” said Trudeau at Friday’s press conference.

Canada views the U.S. as a “safe” third country due to four factors. The first two factors are that the U.S. is party to and viewed as being in alignment with the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1984 Convention Against Torture. The third factor is that there is an agreement between the two countries to handle refugees at the shared border. The final factor is that Canada views the U.S. as having a strong human rights record.

The Safe Third Country Agreement has long been controversial.

In July of 2020, a Canadian federal court judge ruled that the agreement violated Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Justice Ann Marie McDonald called America’s human rights record into question by stating that refugees faced the risk of being arbitrarily detained, sometimes in solitary confinement in the U.S., which violates the guarantee in Canada’s Charter to life, liberty and security of the person.

READ MORE: Canada could provide a safe haven for refugees suffering U.S. abuses

The Canadian Council for Refugees has expressed their concern over this announced expansion.

“Their fundamental rights need to be at the centre of Canada’s concerns. Under international human rights law, Canada has legal obligations to uphold their right to protection. The Agreement will force more people back to the US, where they will be at risk of arbitrary detention and potential return to persecution and possibly death,” reads a statement from the Council.

The Supreme Court of Canada is currently hearing an appeal of the Safe Third Country Agreement, again on the grounds that it violates the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Border issues go beyond refugees

Beyond the issue of refugees, Trudeau announced that the U.S. and Canada planned to create a global coalition to fight the cross border trade of illegal synthetic drugs, such as the opioid fentanyl.

“The opioid overdose crisis is having devastating consequences in our communities. We’re going to disrupt the cross-border movement of chemicals used in the illegal production of fentanyl,” he said.

During the joint press conference, President Biden was also pressed on another issue on Canada’s border, a major oil drilling project that he had approved for northeastern Alaska, in an important and fragile ecological zone the U.S. shares with Canada.

Just prior to his visit to Canada, Biden approved Conoco-Phillips’ $8 billion oil drilling project in this region, which includes the calving grounds of the 200,000-strong Porcupine River caribou, whose migration route takes them back and forth across the international border. The company calls this enterprise the Willow Project.

Biden had previously cancelled Canada’s Keystone XL oil pipeline project that was to transit through the U.S. He was asked by reporters if it was hypocritical of him to approve of an oil drilling project near a wildlife refuge.

“I don’t think it is,” he said. “The difficult decision was on what we do with the Willow Project in Alaska, and my strong inclination was to disapprove of it across the board. But the advice I got from counsel was that if that were the case, we may very well lose in court — lose that case in court to the oil company — and then not be able to do what I really want to do beyond that, and that is conserve significant amounts of Alaskan sea and land forever.”

Biden went on to claim that he believed that his country had protected more acres of wilderness than any administration since Theodore Roosevelt, who created some of the country’s first national parks.

The range of issues discussed between Canada and the U.S. during this recent trip is likely as long as the border itself. Despite the border issues that were addressed at this press conference, what was notably absent was how to equitably treat refugees rather than managing them as a problem, dealing with drug addictions beyond just prosecuting traffickers, and fighting the climate crisis rather than drilling for and burning more fossil fuels.