In Toronto, in a pandemic, homeless people don’t “count.”

If a tree falls in the forest, does anyone hear?

If a homeless person dies in a pandemic, do they count?

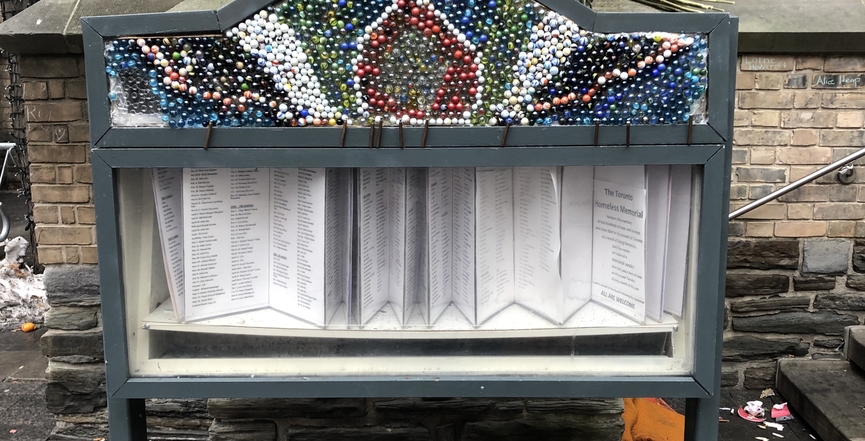

For over 20 years front-line workers and advocates have been tracking homeless deaths and holding a monthly homeless memorial outdoors, rain or shine, at the Church of the Holy Trinity. Names are added to a makeshift outdoor memorial board, people’s lives are honoured and the tragedy of their death called out. There is music, the sharing of grief and a community meal.

In January, 2020 the 1,000th name was added to the memorial.

During all these years, despite appeals for public health attention to a growing travesty, there was essentially no involvement of government bodies such as the chief coroner or Toronto Public Health.

In 2015, Toronto Star reporters Mary Ormsby and Kenyon Wallace met with me and Greg Cook, a front-line worker from Sanctuary and a lead for the monthly memorial. In A Knapsack Full of Dreams. Memoirs of a Street Nurse I tell the story of what happened next.

“They picked our brains about a variety of issues related to homelessness. They reacted with great shock upon learning of the staggering number and nature of homeless deaths and significantly that no government was responsible for documenting them. I realized I had become numb to the numbers.

They ultimately began a three year Toronto Star investigation that included a feature titled “Ontario’s Uncounted Homeless Deaths” (Feb. 21, 2016). It took this journalistic effort to spur on action at City Hall. Only six weeks after the article, city councillor Paul Ainslie tabled a motion at city council requesting that the city track homeless deaths. It passed, and on January 1, 2017, a historic tracking process began with 200 agencies and individuals willingly assisting the city’s public health department. In the first three months, the data was clear: 27 people had died at a rate of 2.1 per week and the average age of death was 51. The circumstances of the deaths, which I was privy to, ranged from overdose, exposure and hypothermia, to early deaths from pneumonia. In six months, the number of deaths had climbed to 46, surpassing Toronto statistics for death by homicide or traffic accidents.

In nine months, the count was 70. At the one year mark, the number was 100 and the average age of death was 48.”

There are now two tracking systems. The city’s shelter system posts deaths in shelters and these numbers go up on the city website about every quarter. The new tracking system, managed by Toronto Public Health, combines shelter deaths and deaths outside the shelter system, including an analysis of trends, cause of death, gender, age etc. These numbers are also reported quarterly and publicly.

The community monthly memorial at Holy Trinity attempts to gather all the data. Note: hospitals do not take part in the Toronto Public Health tracking system, citing privacy legislation.

Homeless people in the pandemic have been left behind. In March, the city stopped posting overnight shelter statistics (an indicator of crowding and lack of vacancy) until the Toronto ombudsman office intervened and an agreement they would post weekly was achieved. The city’s reluctance to enforce physical distancing in shelters meant that a legal coalition had to take the city to court to enforce two-metre physical distancing of beds, cots and mats.

The city’s mask bylaw for indoor common spaces did not apply to shelters, and a mask policy for shelter residents was only announced September 4.

Even in death, homeless people are left behind. The last death statistic on the city website is for January 2020, and is only from the death in shelter data set.

The city’s media spokesperson stated: “In further consultation with our data team, they have advised that due to the city’s ongoing response to our local COVID-19 situation, some recent data updates have not been made to some of our routine reports.”

Citizens For Public Justice socio-economic policy analyst Natalie Appleyard told PressProgress “Reporting publicly on the health outcomes and mortality rates of people experiencing poverty and homelessness is critical in understanding the impacts of our policy and spending decisions, particularly in the midst of a public health crisis.”

From my limited knowledge I can tell you that during the pandemic two women were found dead, one in a tent, one in a sleeping bag outside. At the September memorial two of the four names added had been murdered. The number of overdose deaths in hotel/shelters is staggering. An agency worker has reported to me that she knows of 10 deaths at her shelter. At least four people have died of COVID.

Surely, this is urgent information that begs attention.

While Toronto Public Health and the city’s shelter division shut down tracking homeless deaths, other equally busy city departments continued with data collection and reporting in 2020. I was able to easily find these numbers:

Homicides. As of September 13: 52

In addition: auto theft, break and entry, robbery, sexual assault categories are all included as of September 2020.

Shooting and firearm discharges. As of September 12: 357

Fatal collisions. As of June 2: 781

Toronto Fire responses. As of September 14: Overall fires up 17 per cent since the pandemic.

DineSafe Toronto. As of July: In one week, five.

Photo-radar. As of September 8: more than 22,000 tickets issued.

The pandemic is teaching us many lessons about inequity. As Greg Cook notes:

“One thing that this global pandemic has made even more crystal clear is that some lives aren’t cared for by our city government. Some deaths not even acknowledged. Tracking and publicizing COVID-19 deaths has enabled the media and public to hold the government accountable for its policies. Why not offer the same transparency for those without housing?”

Cathy Crowe is a street nurse, author and filmmaker who works nationally and locally on health and social justice issues.

Image: Cathy Crowe