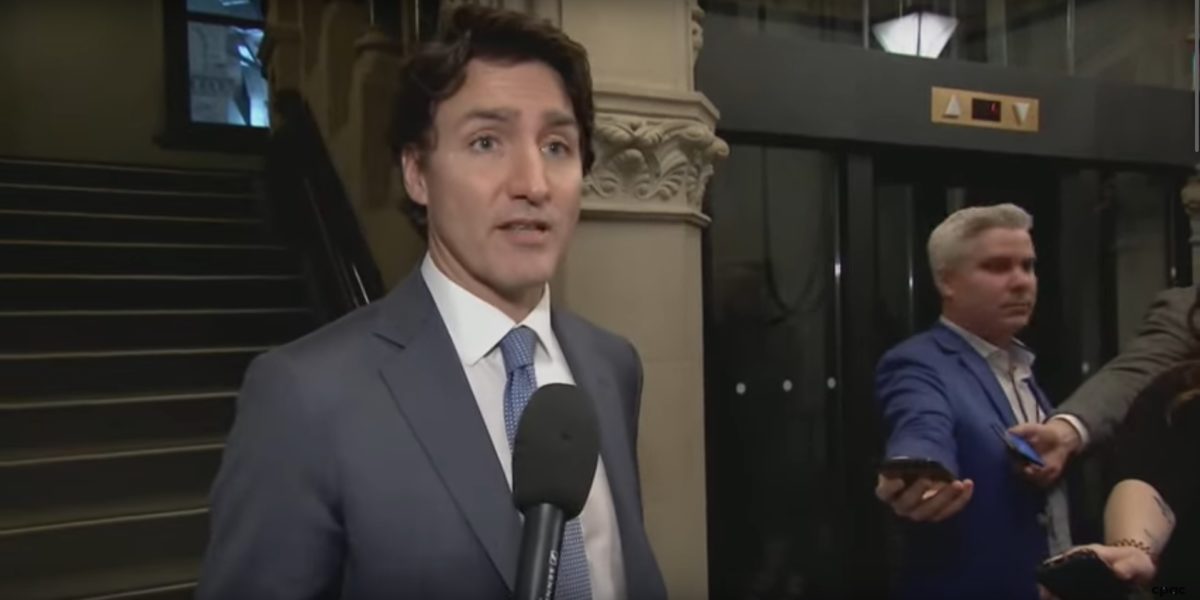

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced late Monday afternoon that he will soon appoint a special rapporteur to look into allegations of Chinese interference in the last federal election.

The rapporteur will recommend further action, which could include a public inquiry.

This initiative will not satisfy opposition leaders, including Trudeau’s governing partner New Democratic leader Jagmeet Singh.

Opposition parties have been calling for a full public and independent inquiry into reports the Chinese spy agency attempted to meddle in Canada’s democratic process.

The current concern over Chinese interference originated in a series of media reports, based on leaked documents from the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS).

Those leaks revealed CSIS believed the Chinese sought a very specific outcome to the 2021 federal election: the continuation of a Liberal minority government.

In aid of that goal, Chinese intelligence is supposed to have provided covert support to a handful of candidates.

Bad memories of the Gomery Commission

In addition to the special rapporteur, the prime minister has asked two existing bodies to investigate the election interference issue.

One body consists of members of both houses of the federal parliament who have been sworn to secrecy, on an ongoing basis: the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians.

The other, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA), is a group of notable citizens who regularly review all intelligence activities in this county. NSIRA’s current chair is former Supreme Court justice Marie Deschamps.

The Trudeau government is not anxious to proceed to a full inquiry on this matter. Many Liberals have bitter memories of the Gomery Commission of 2004, which Prime Minister Paul Martin set up to look into the so-called sponsorship affair.

That scandal revolved around the efforts of the Liberal government headed by Paul Martin’s predecessor Jean Chrétien to enhance the federal presence in Quebec, during a time of heightened support for sovereignty.

Chrétien had asked officials to find festivals and other events in Quebec for the federal government to sponsor. The idea was to get the red Canadian maple leaf featured as prominently as possible in every town and village of Quebec.

It might have been a well-meaning federal branding enterprise, but, sadly, it degenerated into a fiasco of self-dealing and favouritism.

Paul Martin thought he could distance himself from the errors of the man who had preceded him by naming Quebec judge John Gomery to undertake a full public airing of the entire mess.

Martin’s gambit backfired, and badly. He lost his majority in the election later that year, and a year and a half later he lost power altogether.

In light of the Liberals’ bitter experience of inquiries past, Justin Trudeau’s announcement on Monday looks like an exercise in ragging the puck – a carefully orchestrated delay tactic.

To give Trudeau his due, there are varied views on the advisability of a public inquiry. The PM was quick to point that out at his news conference.

The biggest conundrum for such an inquiry would be to deal with the secret and sensitive nature of the highly classified intelligence at the root of the current controversy.

As if to underscore that issue, shortly before Trudeau made his announcement, the RCMP revealed they were investigating the (illegal) CSIS leaks which got the current kerfuffle going.

Poilievre tried to make it harder to investigate electoral crimes

New Democrats have deemed it politically important to distance themselves from their Liberal friends on this matter.

They signed up for enhanced social programs and fairer treatment of such groups as renters and precarious workers, not to give cover to the Liberals when scandals erupt.

As for the Conservatives, they are, as expected, in high dudgeon.

Mind you, the Conservatives have plenty of experience in election interference.

During Conservative PM Stephen Harper’s time in office there were multiple news stories about political operatives using robocalls to imitate the chief electoral officer and direct voters to the wrong polling places – among other electoral pranks.

Marc Mayrand, who headed Elections Canada at the time, told a parliamentary committee he considered it to be “outrageous” for anyone to imitate the chief electoral officer.

In 2012, a group of citizens and the Council of Canadians even brought a case to federal court seeking a byelection in one Toronto riding where election interference shenanigans had allegedly occurred during the campaign of the previous year.

The judge ruled against the complainants, on narrow legal grounds. But he added that during the trial he had seen plenty of evidence of malfeasance during the 2011 federal election.

The Conservative response to the robocall scandal was not a public inquiry.

Quite the contrary.

The Harper government responded with Pierre Poilievre’s oxymoronically named “Fair Elections Act”. That legislation sought to muzzle the chief electoral officer and make it more difficult for neutral officials to uncover acts of electoral interference.

One of the officials Poilievre went after was the Commissioner of Elections, the person responsible for investigating election crimes and misdemeanours.

Poilievre stripped the Commissioner’s office of its independence by moving it into the federal public prosecutor’s office. The public prosecutor reports to an elected politician, the justice minister.

The Trudeau Liberals undid much of Poilievre’s electoral handiwork. Among other measures, they restored the Commissioner’s independence.

The current Commissioner, Carolyn J. Simard, announced last week that she is conducting a thorough investigation of Chinese and other foreign interference in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections.

It would be fair to ask the Conservative leader what, if anything, the Commissioner would now be doing if his reforms were still in force.