Like Karl Nerenberg’s work? Want to expand rabble’s Parliamentary Bureau? Support us on Patreon today!

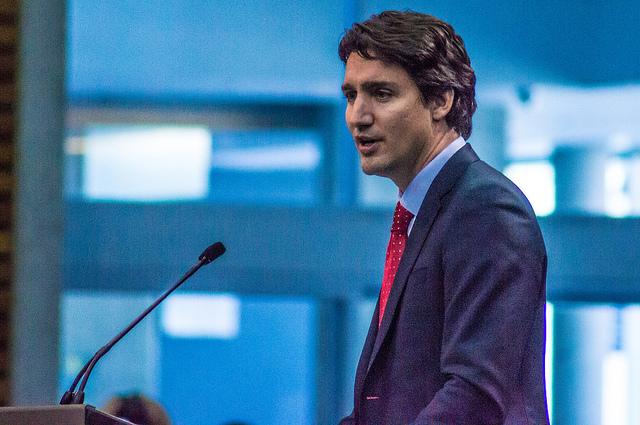

Media stories about the new Trudeau government’s agenda are so numerous they are becoming a genre of their own.

We could call them: Tales of Regime Change.

Pundits and analysts have commented on the tax agenda, the deficit agenda, the challenge of fulfilling Indigenous Canadians’ aspirations, the new look we can expect for foreign policy, the environmental challenges, the hopes for newly liberated scientists, the parliamentary reform agenda, and much more.

Nobody has yet, as far as this writer can tell, taken a look at what we might call the federalism dossier — so here goes.

The conventional wisdom used to be that Conservatives were decentralizers and scrupulously respectful of the rights and prerogatives of the provinces, while Liberals and New Democrats tended to have ambitions for the federal government that might tread on the provinces’ toes.

The Harper government defied that conventional wisdom.

Stephen Harper refused to meet with the premiers, as a group, and even took unprecedented, partisan shots at premiers, such as Rachel Notley, who happened to be of parties different from his.

When it came to areas of shared constitutional jurisdiction, such as criminal justice, Harper’s attitude was arrogant and condescending.

Many provincial governments, most notably that of Quebec, were vehemently opposed to such Harper government law and order measures as mandatory minimum sentences. They believed they had the right to be fully consulted since most policing and a good part of the judicial system fall under provincial jurisdiction.

Harper was contemptuously indifferent to their concerns, however.

He did not view federalism as a collaborative system that works through negotiation, consultation and compromise.

In Harper’s worldview the Canadian federation is a series of silos. My government, he used to argue, does not need provincial advice to fulfill its own constitutional role –and the provinces should stick to their knitting and fulfill theirs.

Regular First Ministers’ meetings and much more

The new prime minister will have a chance to take a very different approach.

He has signalled his intention to make big changes by inviting the premiers to Paris for the climate change summit.

We can also expect Justin Trudeau to revive the practice of regular First Ministers meetings, and to seek provincial input on legislation in which the provinces might have a great interest, such as pension reform or decriminalization of marijuana.

There will be a measure of irony in all that, because Justin Trudeau’s father had famously tense relations with the provinces.

Remember the National Energy Program?

Or, Pierre Trudeau’s original effort to unilaterally repatriate the Canadian constitution, without provincial concurrence?

Or the way he ultimately amended the constitution, without the accord of the Quebec government?

In his relations with the federal government’s constitutional partners, the provinces, Pierre Trudeau did not sulk in a passive-aggressive fashion, as did Harper.

Trudeau senior was openly assertive, and too often confrontational.

Justin Trudeau has already promised to roll back the über-centralization of power within the Prime Minister’s Office, which his father put in motion.

We can also expect him to take a very different approach to relations with the provinces than did his father.

We’ll see how that works, in practice and over time.

First-past-the-post rewards political regionalism

There is one area, however, where measures the new government might enact could change the nature of Canadian federalism for generations.

That area is electoral reform.

Changing the federal voting system is usually portrayed as a matter of fairness, of making every vote count.

Those who argue for reform say the current winner-take-all, first-past-the-post system breeds political apathy and cynicism, because voters who did not happen to choose the winning candidate in their riding can legitimately feel their votes were wasted.

But there is another pernicious aspect to Canada’s first-past-the-post system.

For the most part, first-past-the-post rewards parties that manage to geographically concentrate their votes.

We saw an extreme version of that in the 1993 election, when the Proressive Conservative (PC) party got only two seats with over 16% of the popular vote, while the separatist Bloc Québecois won 54 seats with slightly more than half the Conservatives’ vote total.

The PC vote was spread thinly over all the ridings in the country, while the Bloc only bothered to run candidates in Quebec’s 75 ridings.

The third place party, Reform, of which Stephen Harper was one of the newly-elected members, got only slightly more votes than the PCs, but about 25 times the number of seats.

Its vote, too, was geographically concentrated. It ran no candidates in Quebec and focused most of its efforts on the four western provinces, where it won all but one of its seats.

Electoral systems create incentives for political behaviour, and some of the incentives of first-past-the-post have had a pernicious impact on the unity and cohesion of the Canadian federation.

Let us imagine that back in 1993 we had a different electoral system.

Under most alternative systems, the Bloc would have had a much smaller number of seats and national parties such as the Conservatives and New Democrats would have had more.

If the Bloc, then led by Lucien Bouchard, had been more of a rump than a powerhouse in Ottawa maybe Canadian history would be different.

We might still have had to endure the Quebec referendum of 1995, but the Bloc leader might not have had the stature to assume the key and nearly decisive role he did in that near death experience for the Canadian federation.

The entirely western-focused Reform party would also have been relatively smaller vis-à-vis the PCs. In the merger process that happened about a decade later the balance of power between the two would have been very different.

It would not have been inevitable that we would end up with Stephen Harper as the merged party’s leader, and, ultimately, prime minister.

We might have had a less polarizing and more centrist Conservative leader.

Do not measure longterm impact of current voting system by 2015 election

The most important lesson here is that it is unhealthy for Canadian federalism to have an electoral system that artificially exaggerates political parties’ popularity in some regions while it underrepresents them in others.

At first blush, the current election seems to have produced a far less skewed result than that of 1993.

Still, nearly half the voters of New Brunswick who picked parties other than the Liberals got not a single seat for their troubles. Nor did the one fifth of voters who chose the NDP in Newfoundland and Labrador — to cite just two examples.

In giant Ontario, all parties are represented, but does it make sense that all save two of the 49 MPs from the vast Greater Toronto Area (GTA) are from one political party?

The Liberals did well in the GTA, but not that well.

Is it healthy for Canadian democracy if voters who supported the Conservatives or New Democrats in Canada’s largest metropolitan region are so vastly under-represented, or without representation at all?

One could reasonably argue that it is not. Would it not be useful for a large and important region such as metropolitan Toronto to have a number of vigorous opposition voices in the House of Commons, voices who would speak up for local concerns when government members might remain silent?

The October election produced a good result for the Liberals.

They have balanced representation across the country, something no party has achieved since the 1980s. But the first-past-the-post system does not usually produce such a result.

Even Jean Chrétien’s three consecutive majorities depended on his getting all or almost all the seats in Ontario, while failing to win significant representation in francophone Quebec or in western provinces such as Alberta.

When he sets out to reform the electoral system, as he has solemnly promised to do, the newly elected prime minister will want to consider the federalism, as well as the fairness, dimension.

In evaluating the impact of first-past-the-post, Justin Trudeau would be well advised to look beyond the most recent election results to possible outcomes of future elections.

As they have in the past, future first-past-the-post elections would likely exaggerate the power and influence of political parties that seek not to find common ground among Canadians but to exacerbate regional differences.

That would not be good for the longterm health of the federal system in Canada.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.